As the 3rd presenter during the morning session of the American Society for Dermatologic Surgery Meeting, “Emerging Concepts,” Saranya Wyles, MD, PhD, assistant professor of dermatology, pharmacology, and regenerative medicine in the department of dermatology at the Mayo Clinic in Rochester, Minnesota, explored the hallmarks of skin aging, the root cause of aging and why it occurs, and regenerative medicine. Wyles first began with an explanation of how health care is evolving. In 21st-century health care, there has been a shift in how medical professionals think about medicine. Traditionally, the first approach was to fight diseases, such as cancer, inflammatory conditions, or autoimmune disorders. Now, the thought process is changing to a root cause approach with a curative option and how to rebuild health. Considering how to overcome the sequence of the different medications and treatments given to patients is rooted in regenerative medicine principles.

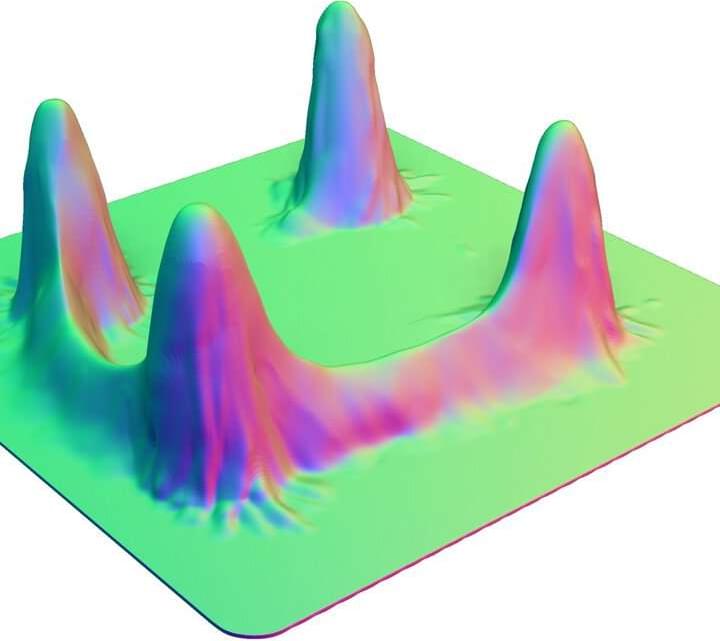

For skin aging, there is a molecular ‘clock’ that bodies follow. Within the clock are periods of genomic instability, telomere attrition, and epigenetic alterations, and Wyles’ lab focuses on cellular senescence.

“We’ve heard a lot at this conference about bio stimulators, aesthetics, and how we can stimulate our internal mechanisms of regeneration. Now, the opposite force of regeneration is the inhibitory aging hallmarks which include cellular senescence. So, what is cell senescence? This is a state that the cell goes into, similar to apoptosis or proliferation, where the cell goes into a cell cycle arrest so instead of dividing apoptosis, leading to cell death, the cell stays in this zombie state,” said Wyles.