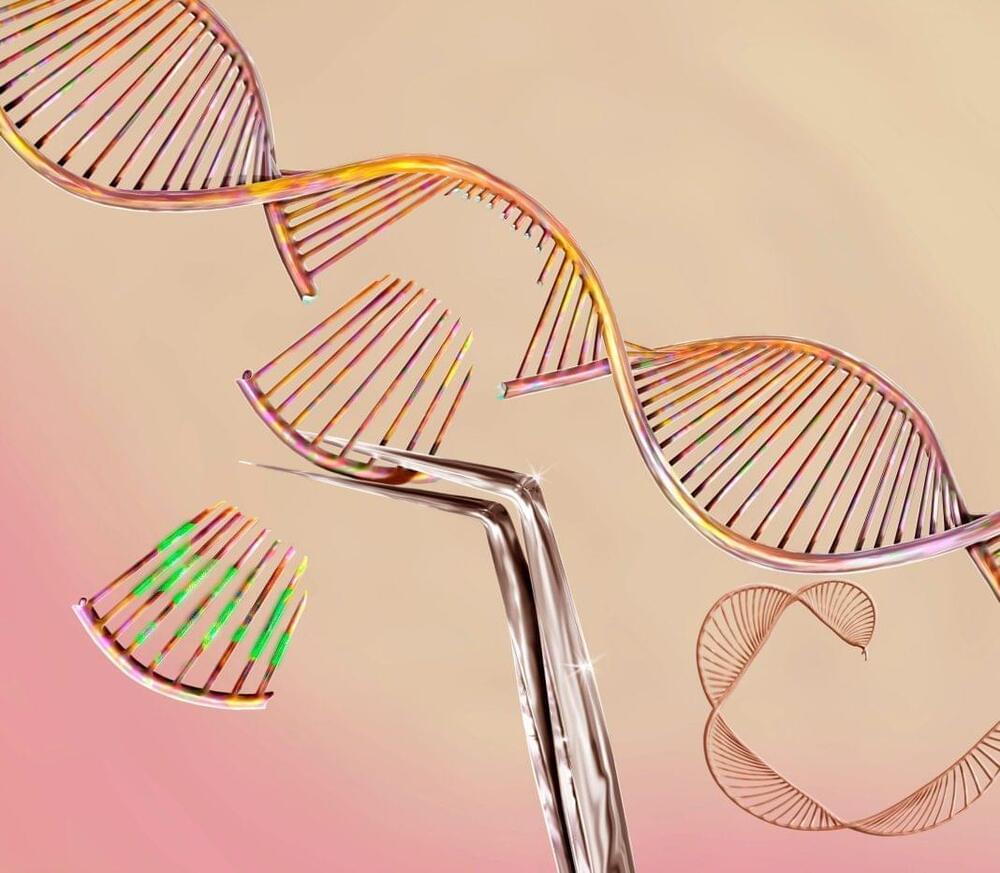

Gene therapy has been headline news in recent years, in part due to the rapid development of biotechnology that enables doctors to administer such treatments. Broadly, gene therapies are techniques used to treat or prevent disease by tweaking the content or expression of cells’ DNA, often by replacing faulty genes with functional ones.

The term “gene therapy” sometimes appears alongside misinformation about mRNA vaccines, which include the Pfizer and Moderna COVID-19 vaccines. These vaccines contain mRNA, a genetic cousin of DNA, that prompts cells to make the coronavirus “spike protein.” The vaccines don’t alter cells’ DNA, and after making the spike, cells break down most of the mRNA. Other COVID-19 shots include the viral vector vaccines made by AstraZeneca and Johnson & Johnson, which deliver DNA into cells to make them build spike proteins. The cells that make spike proteins, using instructions from either mRNA or viral vector vaccines, serve as target practice for the immune system, so they don’t stick around long. That’s very, very different from gene therapy, which aims to change cells’ function for the long-term.