Recent research published in Nature Communications from the Nuffield Department of Clinical Neurosciences at the University of Oxford has identified 15 modifiable risk factors for dementia, and of those diabetes, alcohol intake, and traffic-related air pollution are the most harmful.

Previous research from this group revealed an area of weakness in the brain of a specific network of higher-order regions that only develop later in adolescence but also display earlier degeneration in old age, and they showed that this brain network is particularly vulnerable to Alzheimer’s disease and schizophrenia. This study investigated genetic and modifiable influences on these regions by utilizing data from the UK Biobank.

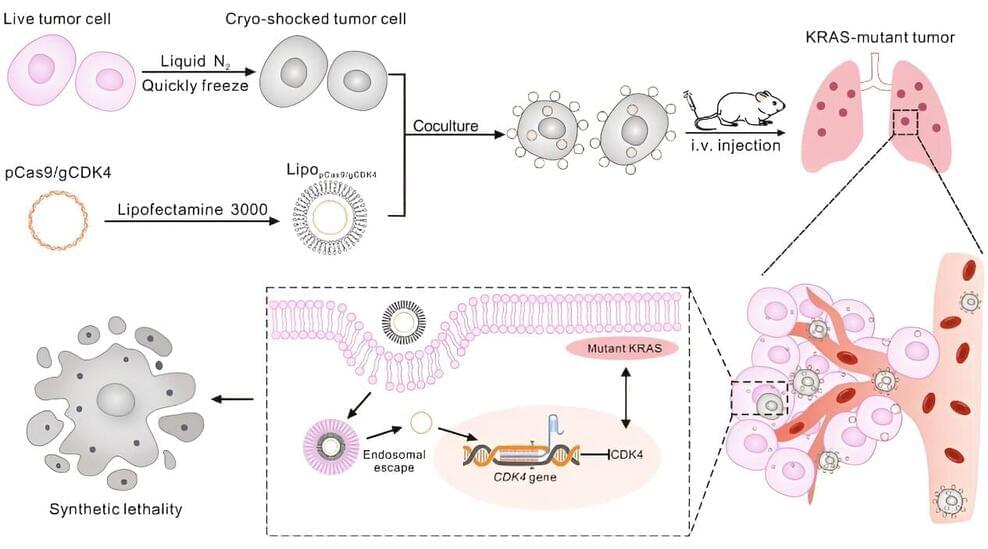

This study examined 161 risk factors for dementia by analyzing brain scans of 40,000 people over the age of 45 years old. The modifiable risk factors were ranked by their impact on the vulnerable brain network over and above the natural effects of aging, classifying them into 15 broad categories: blood pressure, diabetes, weight, cholesterol, smoking, inflammation, hearing, sleep, diet, physical activity, education, socialism, pollution, alcohol consumption, and depressive mood.