Join us on Patreon! https://www.patreon.com/MichaelLustgartenPhDDiscount Links: Epigenetic, Telomere Testing: https://trudiagnostic.com/?irclickid=U-s3Ii2r7x…

Category: genetics – Page 169

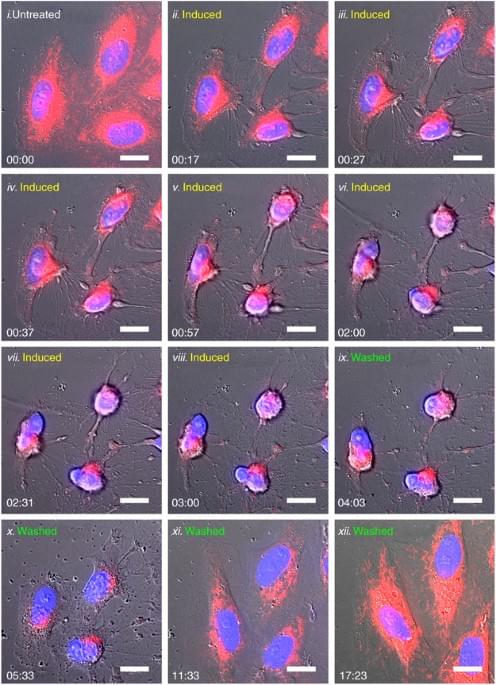

Reversibility of apoptosis in cancer cells

Year 2008 I think that this reversing of the death processes in cancer could be genetically engineered in humans to essentially reverse death on the whole human body.

British Journal of Cancer volume 100, pages 118–122 (2009) Cite this article.

Anti-Aging Gene Shown To Rewind Heart Age by 10 Years

face_with_colon_three year 2023 The ultimate goal is to use crispr to modify genetic programming for eternal life this an example of heart age reversal.

An anti-aging gene found in centenarians has been shown to reverse the heart’s biological age by 10 years. This groundbreaking discovery, published in the journal Cardiovascular Research and led by scientists from the University of Bristol and MultiMedica Group in Italy, offers a potential target for heart failure patients.

Individuals who carry healthy mutant genes, commonly found in populations known for exceptional longevity such as the “blue zones,” often live to 100 years or more and remain in good health. These carriers are also less susceptible to cardiovascular complications. Scientists funded by the British Heart Foundation believe the gene helps keep their hearts youthful by guarding against diseases related to aging, such as heart failure.

In this new study, researchers demonstrate that one of these healthy mutant genes, previously proved particularly frequent in centenarians, can protect cells collected from patients with heart failure requiring cardiac transplantation.

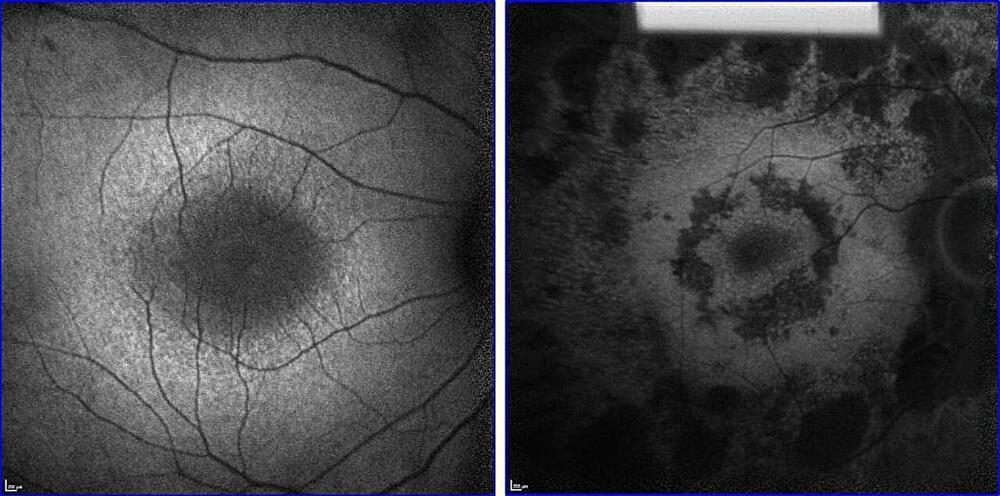

Revitalizing Vision: Metabolome Rejuvenation Can Slow Retinal Degeneration

Gene therapy may be the best hope for curing retinitis pigmentosa (RP), an inherited condition that usually leads to severe vision loss and blinds 1.5 million people worldwide.

But there’s a huge obstacle: RP can be caused by mutations in over 80 different genes. To treat most RP patients with gene therapy, researchers would have to create a therapy for each gene—a nearly impractical task using current gene therapy strategies.

A more universal treatment may be forthcoming. Using CRISPR-based genome engineering, scientists at Columbia University Vagelos College of Physicians and Surgeons are designing a gene therapy with the potential to treat RP patients regardless of the underlying genetic defect.

RNA Molecules in Brain Nerve Cells Display Lifelong Stability

Certain RNA molecules in the nerve cells in the brain last a life time without being renewed. Neuroscientists from Friedrich-Alexander-Universität Erlangen-Nürnberg (FAU) have now demonstrated that this is the case together with researchers from Germany, Austria and the USA. RNAs are generally short-lived molecules that are constantly reconstructed to adjust to environmental conditions. With their findings that have now been published in the journal Science, the research group hopes to decipher the complex aging process of the brain and gain a better understanding of related degenerative diseases.

Most cells in the human body are regularly renewed, thereby retaining their vitality. However, there are exceptions: the heart, the pancreas and the brain consist of cells that do not renew throughout the whole lifespan, and yet still have to remain in full working order. “Aging neurons are an important risk factor for neurodegenerative illnesses such as Alzheimer’s,” says Prof. Dr. Tomohisa Toda, Professor of Neural Epigenomics at FAU and at the Max Planck Center for Physics and Medicine in Erlangen. “A basic understanding of the aging process and which key components are involved in maintaining cell function is crucial for effective treatment concepts:”

In a joint study conducted together with neuroscientists from Dresden, La Jolla (USA) and Klosterneuburg (Austria), the working group led by Toda has now identified a key component of brain aging: the researchers were able to demonstrate for the first time that certain types of ribonucleic acid (RNA) that protect genetic material exist just as long as the neurons themselves. “This is surprising, as unlike DNA, which as a rule never changes, most RNA molecules are extremely short-lived and are constantly being exchanged,” Toda explains.

A recent study explores how the brain learns to seek reward

Study links dopamine to learning via optogenetics:

A new study reveals dopamine’s role in animal behavior having potential applications in education and artificial intelligence.

Are you ready for CRISPR? Because the gene-editing technology is already impacting the food we eat

You’ve probably heard about the gene-editing technology CRISPR. The massive biotech breakthrough, which has emerged in the last decade, has mainly been touted for the ways it will let scientists edit the human genome — hopefully to cure genetic diseases or perhaps, more worryingly, to create “designer babies.” But CRISPR is also being used in another area, the world of food.

Cultural anthropologist Dr. Lauren Crossland-Marr hosts the five-episode podcast A CRISPR Bite. She takes listeners into labs as researchers tinker with the genes in what we eat and drink. What, exactly, are they trying to achieve? And what’s at stake?

Seven diseases CRISPR technology could cure

Using this natural process as a basis, scientists developed a gene-editing tool called CRISPR/Cas that can cut a specific DNA sequence by simply providing it with an RNA template of the target sequence. This allows scientists to add, delete, or replace elements within the target DNA sequence. Slicing a specific part of a gene’s DNA sequence with the help of the Cas9 enzyme, aids in DNA repair.

This system represented a big leap from previous gene-editing technologies, which required designing and making a custom DNA-cutting enzyme for each target sequence rather than simply providing an RNA guide, which is much simpler to synthesize.

CRISPR gene editing has already changed the way scientists do research, allowing a wide range of applications across multiple fields. Here are some of the diseases that scientists aim to tackle using CRISPR/Cas technology, testing its possibilities and limits as a medical tool.

Risk Factors For Faster Brain Aging

Recent research published in Nature Communications from the Nuffield Department of Clinical Neurosciences at the University of Oxford has identified 15 modifiable risk factors for dementia, and of those diabetes, alcohol intake, and traffic-related air pollution are the most harmful.

Previous research from this group revealed an area of weakness in the brain of a specific network of higher-order regions that only develop later in adolescence but also display earlier degeneration in old age, and they showed that this brain network is particularly vulnerable to Alzheimer’s disease and schizophrenia. This study investigated genetic and modifiable influences on these regions by utilizing data from the UK Biobank.

This study examined 161 risk factors for dementia by analyzing brain scans of 40,000 people over the age of 45 years old. The modifiable risk factors were ranked by their impact on the vulnerable brain network over and above the natural effects of aging, classifying them into 15 broad categories: blood pressure, diabetes, weight, cholesterol, smoking, inflammation, hearing, sleep, diet, physical activity, education, socialism, pollution, alcohol consumption, and depressive mood.