One of the most detailed 3D maps of how the human chromosomes are organized and folded within a cell’s nucleus is published in Nature.

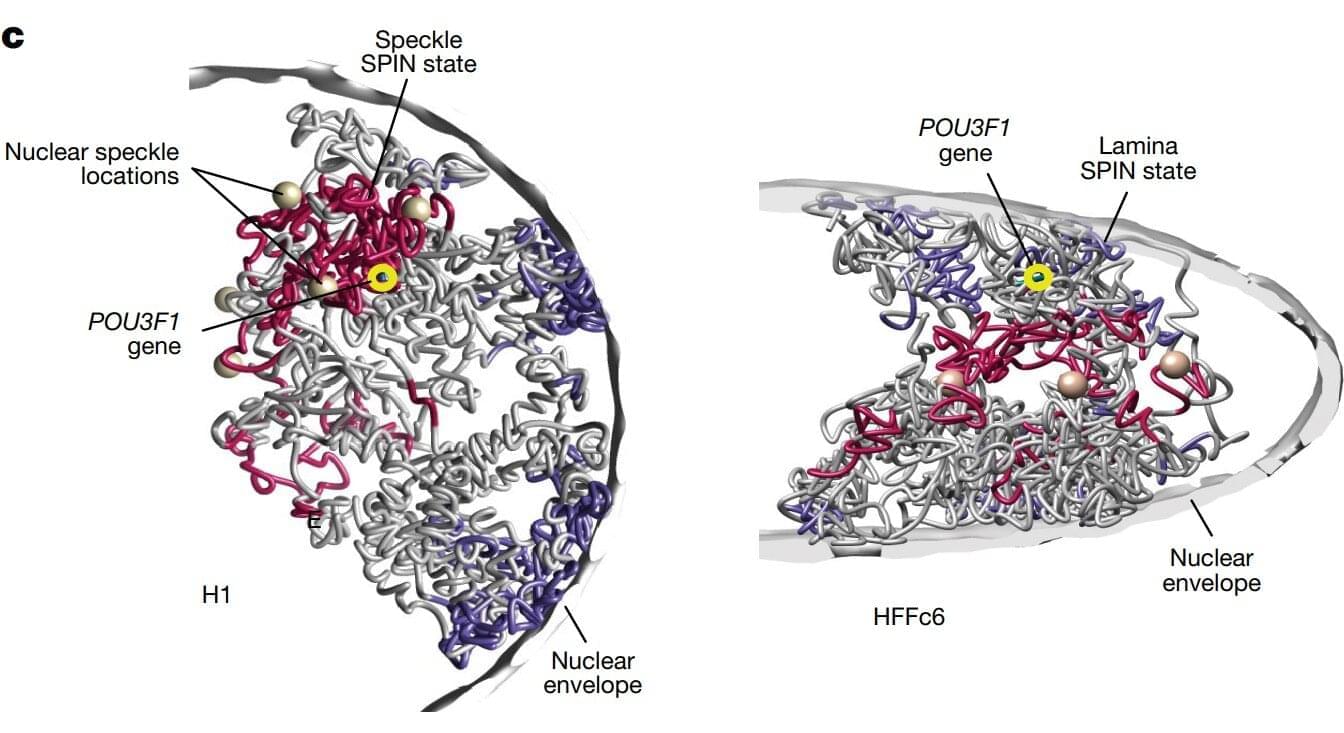

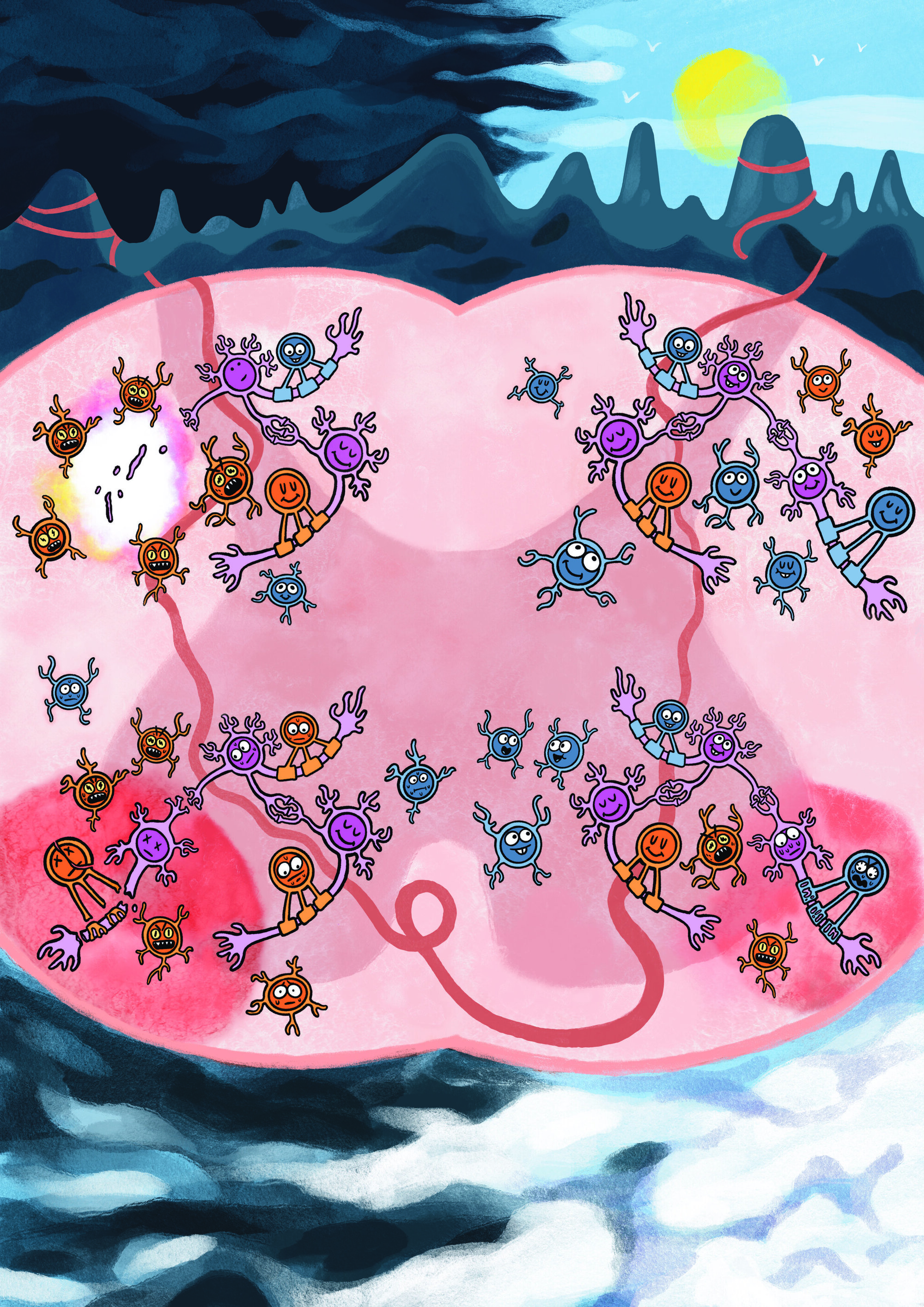

Chromosomes are thread-like structures that carry a cell’s genetic information inside the nucleus. Rather than existing as loose strands or only as the familiar X-shapes seen in textbooks, chromosomes fold into specific three-dimensional forms. How they fold, the structures they form, and their placement play crucial roles in maintaining proper cellular functions, gene expression, and DNA replication.

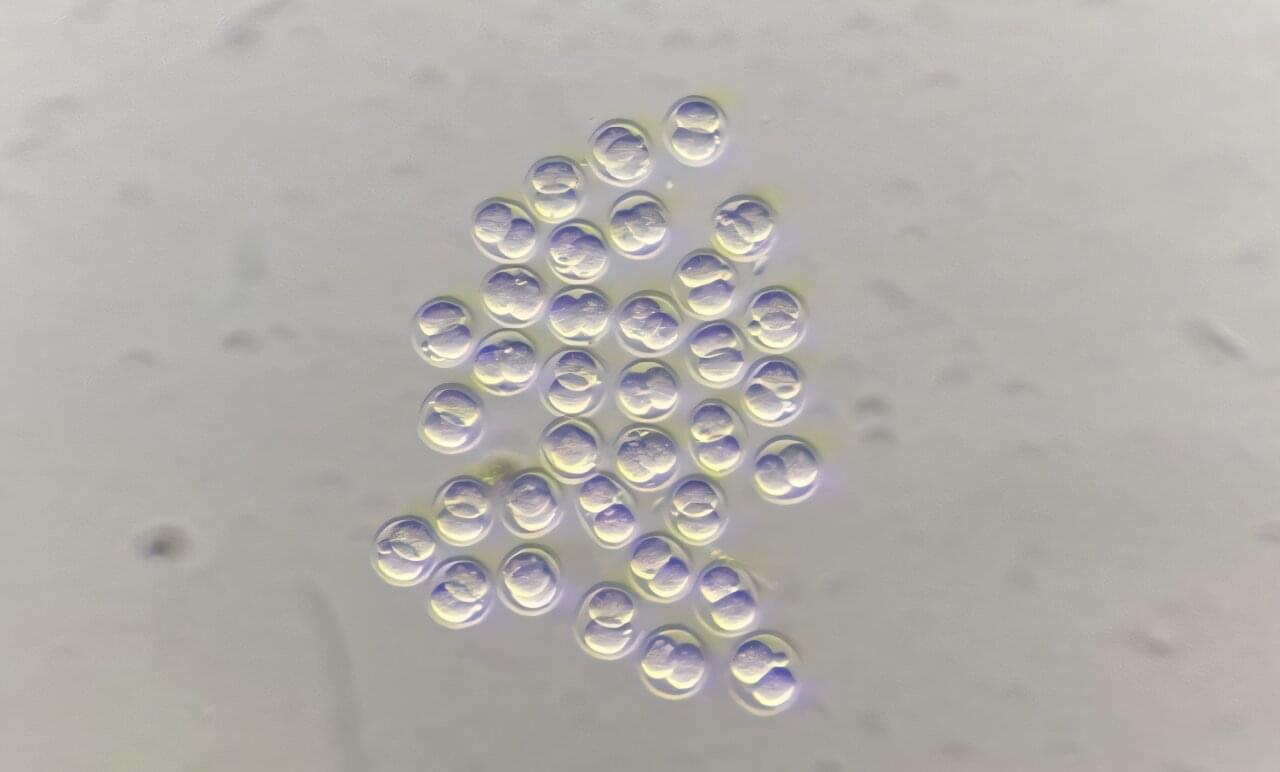

The team involved in the 4D Nucleome Project, whose goal was to understand the 3D organization of human chromosomes in the nucleus and how it changes over time, identified over 140,000 DNA looping interactions in human embryonic stem cells and fibroblasts. They also presented computational methods that can predict genome folding solely from its DNA sequence, making it easier to determine how genetic variations—including those linked to disease—affect genome structure and function.