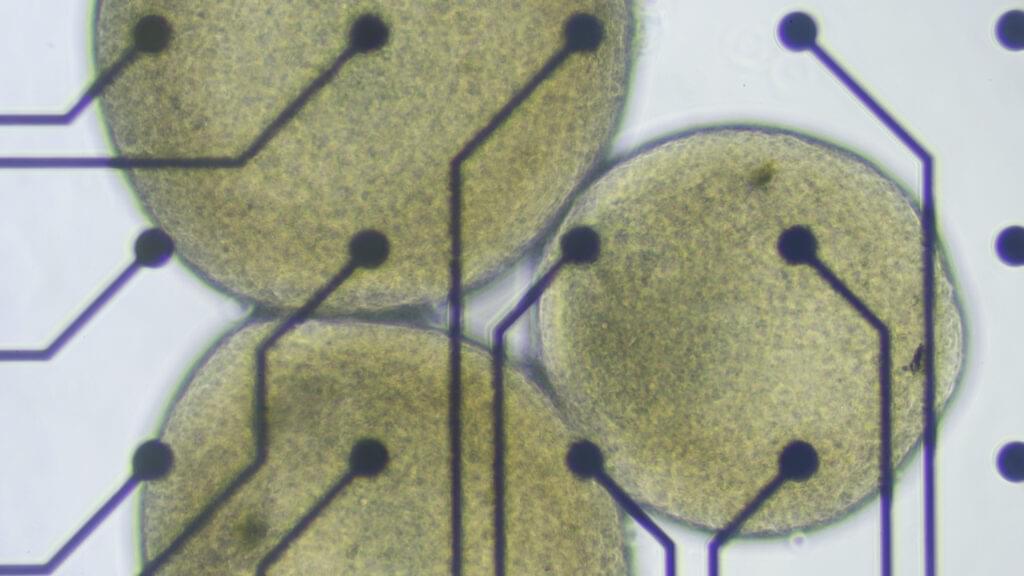

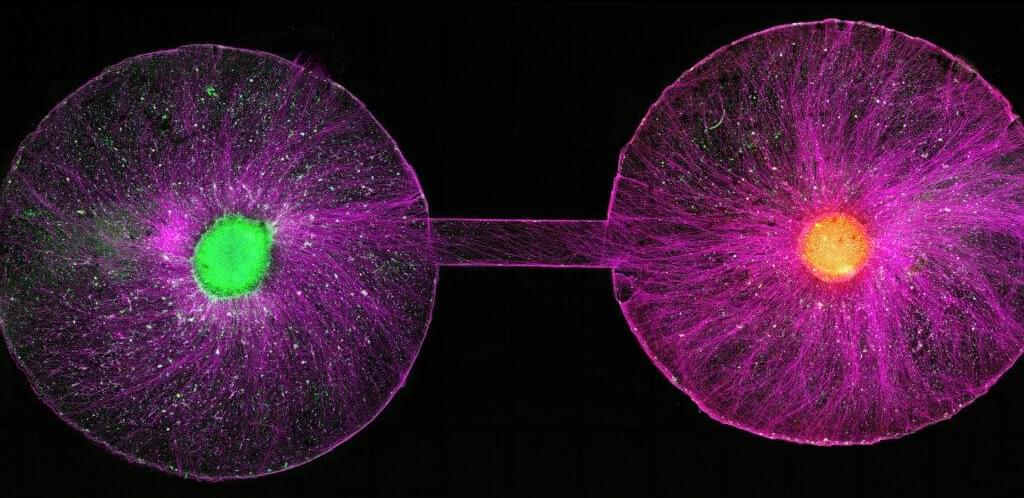

For the brain organoids in Lena Smirnova’s lab at Johns Hopkins University, there comes a time in their short lives when they must graduate from the cozy bath of the bioreactor, leave the warm, salty broth behind, and be plopped onto a silicon chip laced with microelectrodes. From there, these tiny white spheres of human tissue can simultaneously send and receive electrical signals that, once decoded by a computer, will show how the cells inside them are communicating with each other as they respond to their new environments.

More and more, it looks like these miniature lab-grown brain models are able to do things that resemble the biological building blocks of learning and memory. That’s what Smirnova and her colleagues reported earlier this year. It was a step toward establishing something she and her husband and collaborator, Thomas Hartung, are calling “organoid intelligence.”

Tead More

Another would be to leverage those functions to build biocomputers — organoid-machine hybrids that do the work of the systems powering today’s AI boom, but without all the environmental carnage. The idea is to harness some fraction of the human brain’s stunning information-processing superefficiencies in place of building more water-sucking, electricity-hogging, supercomputing data centers.

Despite widespread skepticism, it’s an idea that’s started to gain some traction. Both the National Science Foundation and DARPA have invested millions of dollars in organoid-based biocomputing in recent years. And there are a handful of companies claiming to have built cell-based systems already capable of some form of intelligence. But to the scientists who first forged the field of brain organoids to study psychiatric and neurodevelopmental disorders and find new ways to treat them, this has all come as a rather unwelcome development.

At a meeting last week at the Asilomar conference center in California, researchers, ethicists, and legal experts gathered to discuss the ethical and social issues surrounding human neural organoids, which fall outside of existing regulatory structures for research on humans or animals. Much of the conversation circled around how and where the field might set limits for itself, which often came back to the question of how to tell when lab-cultured cellular constructs have started to develop sentience, consciousness, or other higher-order properties widely regarded as carrying moral weight.