The James Webb Space Telescope has revolutionized the way we look at the universe in less.

than a year. Since its launch on December 25, 2021 multiple images captured by the largest.

telescope with potentially the highest infrared resolution and sensitivity have been going viral.

around the globe. James Webb is no doubt the most advanced telescope in human history. The.

telescope’s integrated science instrument module or ISIM framework provides it with electrical.

power, computing framework, cooling capability and structural stability. The ISIM also holds the.

four science instruments and the guide camera of the telescope. The infrared imager NIRICam.

serves as the Observatory’s wavefront sensor while the NIRISpec performs spectroscopy over.

the same wavelength range as that of NIRICam. The Mid-Infrared Instrument measures the mid.

to long infrared wavelengths and the Fine Guidance Center and Near Infrared Imager and.

Slitless Spectrograph is used to stabilize the line of sight during the science observations. So far.

the images and data received from the JWST are well worth the ten billion spent on building this.

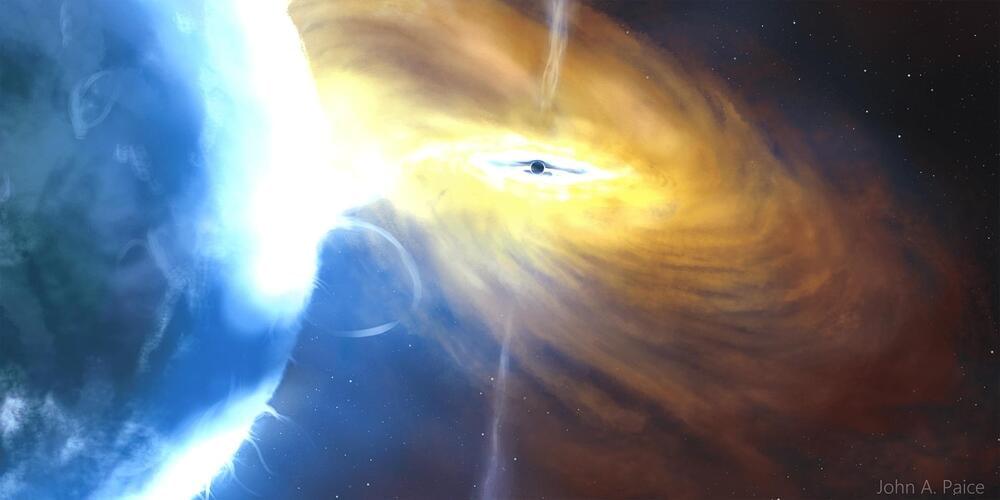

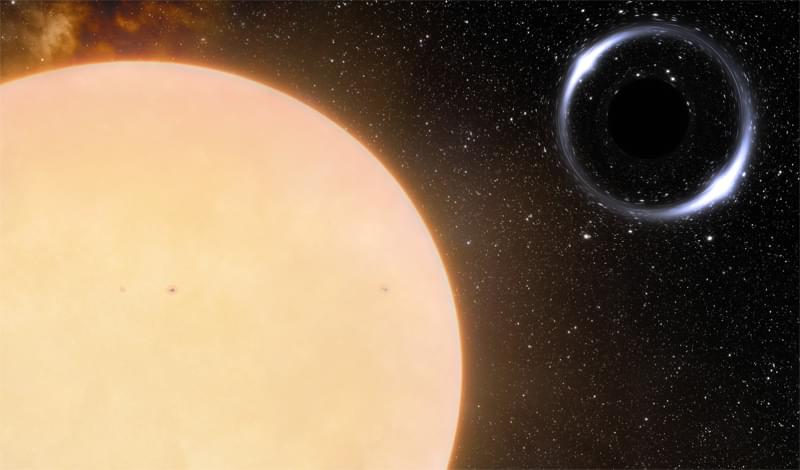

miraculous invention. The first ever in ages from the telescope were revealed to the world on.

July 12, 2022 and experts believe these pictures from the largest and most powerful telescope.

in the world demonstrate Webb at its absolute best, fully prepared to further unravel the infrared universe. These included images of cosmic cliffs in the carina nebula, exoplanet WASP-06b.

southern ring nebula, Stephen’s quintet and the brilliant deep field view of the universe. But.

these were just the first batch, since then the James Webb Telescope has provided scientists.

with even more dazzling and awe-inspiring images of the cosmos. Some of these images have.

left astronomers and cosmologists quite confused. A flood of astronomical papers has been.

published since the revelation of these images and data from the JWST, a few of these papers.

have incited panic among the cosmologists. But what exactly is the reason behind this wave of.

panic? Well, it’s the assumption that the findings of James Webb Space Telescope are blatantly.

and repeatedly contradicting the Big Bang Theory. In order to better understand what’s going.

on, we first need to understand what the Big Bang exactly is.

Disclaimer Fair Use:

1. The videos have no negative impact on the original works.

2. The videos we make are used for educational purposes.

3. The videos are transformative in nature.

4. We use only the audio component and tiny pieces of video footage, only if it’s necessary.

DISCLAIMER:

Our channel is purely made for entertainment purposes, based on facts, rumors, and fiction.

Copyright Disclaimer under section 107 of the Copyright Act 1976, allowance is made for “fair use” for purposes such as criticism, comment, news reporting, teaching, scholarship, education, and research. Fair use is a use permitted by copyright statutes that might otherwise be infringing.