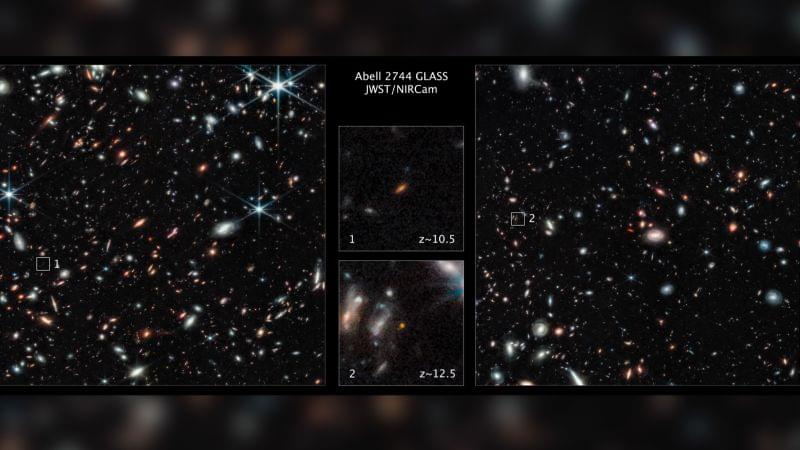

The James Webb Space Telescope has spied one of the earliest galaxies formed after the big bang, about 350 million years after the universe began.

The galaxy, called GLASS-z12, and another galaxy formed about 450 million years after the big bang, were found over the summer, shortly after the powerful space observatory began its infrared observations of the cosmos.

Webb’s capability to look deeper into the universe than other telescopes is revealing previously hidden aspects of the universe, including astonishingly distant galaxies such as these two finds.