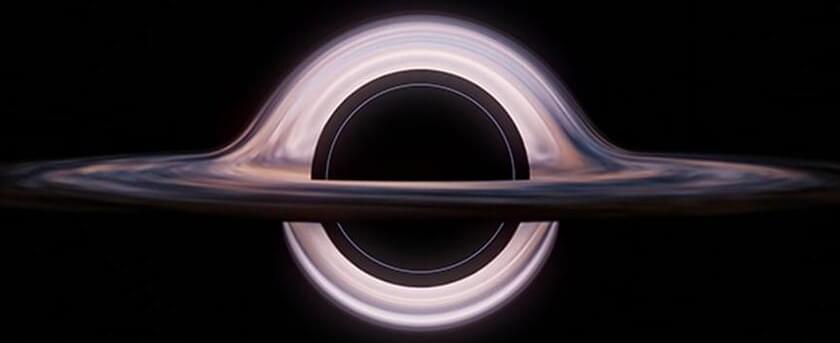

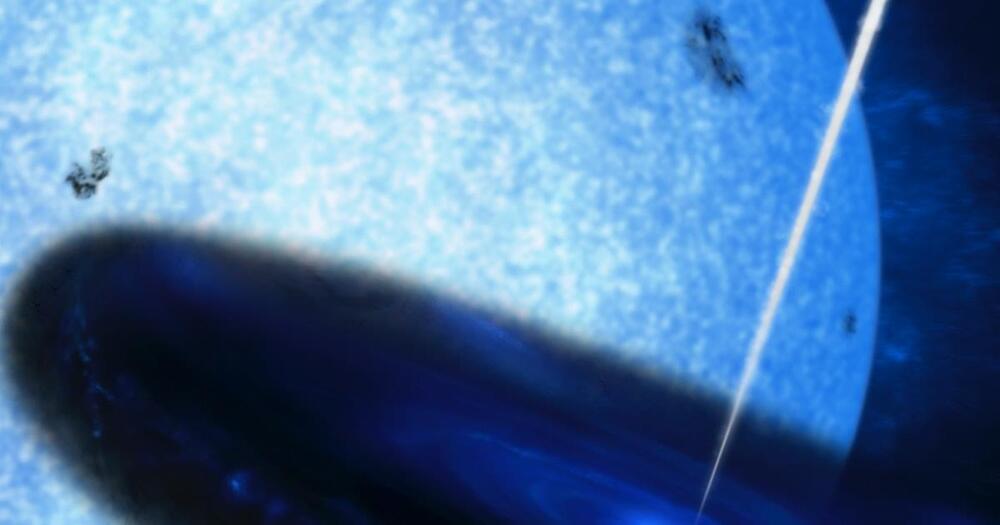

Hypothetical bridges connecting distant regions of space (and time) could more or less look like garden variety black holes, meaning it’s possible these mythical beasts of physics have already been seen.

Thankfully however, if a new model proposed by a small team of physicists from Sofia University in Bulgaria is accurate, there could still be a way to tell them apart.

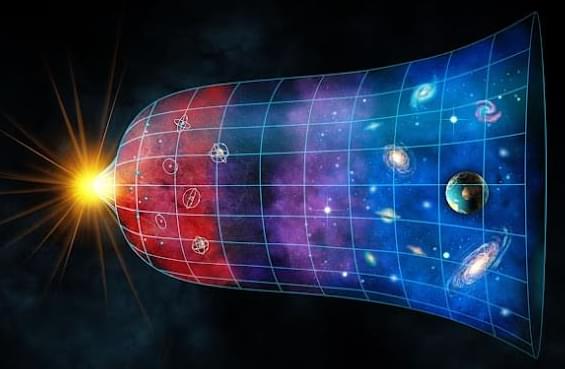

Play around with Einstein’s general theory of relativity long enough, it’s possible to show how the spacetime background of the Universe can form not only deep gravitational pits where nothing escapes – it can form impossible mountain peaks which can’t be climbed.