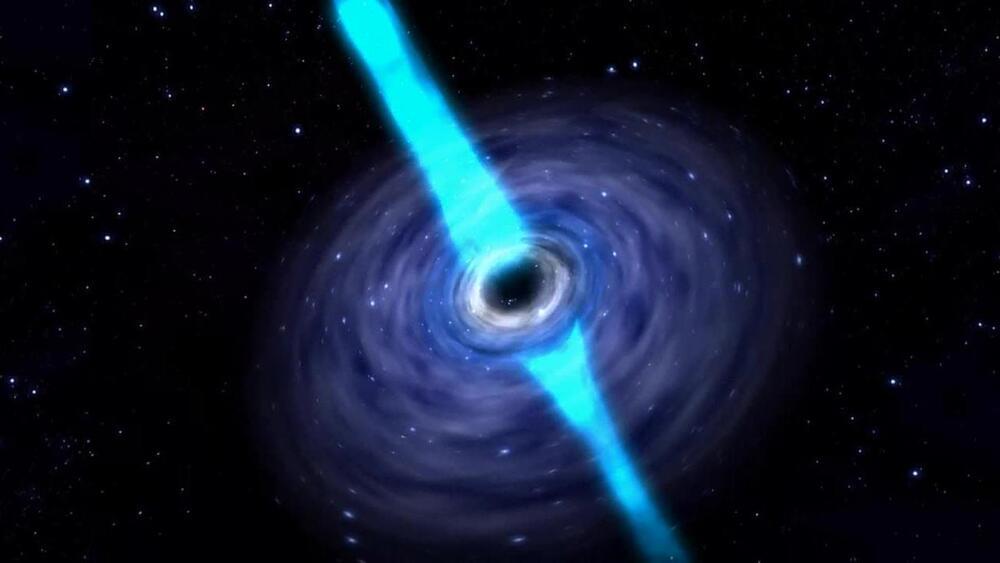

How are chemical elements produced in our Universe? Where do heavy elements like gold and uranium come from? Using computer simulations, a research team from the GSI Helmholtzzentrum für Schwerionenforschung in Darmstadt, together with colleagues from Belgium and Japan, shows that the synthesis of heavy elements is typical for certain black holes with orbiting matter accumulations, so-called accretion disks. The predicted abundance of the formed elements provides insight into which heavy elements need to be studied in future laboratories — such as the Facility for Antiproton and Ion Research (FAIR), which is currently under construction — to unravel the origin of heavy elements. The results are published in the journal Monthly Notices of the Royal Astronomical Society.

All heavy elements on Earth today were formed under extreme conditions in astrophysical environments: inside stars, in stellar explosions, and during the collision of neutron stars. Researchers are intrigued with the question in which of these astrophysical events the appropriate conditions for the formation of the heaviest elements, such as gold or uranium, exist. The spectacular first observation of gravitational waves and electromagnetic radiation originating from a neutron star merger in 2017 suggested that many heavy elements can be produced and released in these cosmic collisions. However, the question remains open as to when and why the material is ejected and whether there may be other scenarios in which heavy elements can be produced.

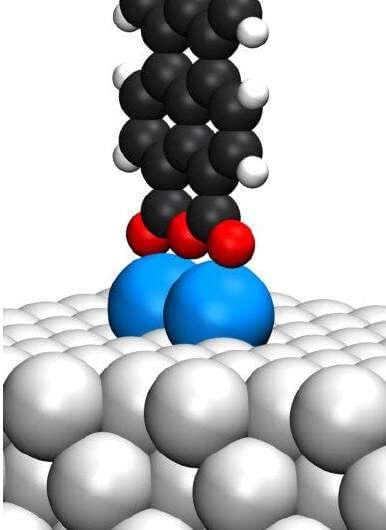

Promising candidates for heavy element production are black holes orbited by an accretion disk of dense and hot matter. Such a system is formed both after the merger of two massive neutron stars and during a so-called collapsar, the collapse and subsequent explosion of a rotating star. The internal composition of such accretion disks has so far not been well understood, particularly with respect to the conditions under which an excess of neutrons forms. A high number of neutrons is a basic requirement for the synthesis of heavy elements, as it enables the rapid neutron-capture process or r-process. Nearly massless neutrinos play a key role in this process, as they enable conversion between protons and neutrons.