In my new Newsweek Op-Ed, I tackle a primary issue many people have with trying to stop aging and death via science. Hopefully this philosophical argument will allow more resources & support into the life extension field:

Philosophers often say if humans didn’t die, we’d be bored out of our minds. This idea, called temporal scarcity, argues the finitude of death is what makes life worth living. Transhumanists, whose most urgent goal is to use science to overcome biological death, emphatically disagree.

For decades, the question of temporal scarcity has been debated and analyzed in essays and books. But an original idea transhumanists are putting forth is reinvigorating the debate. It doesn’t discount temporal scarcity in biological humans; it discounts it in what humans will likely become in the future—cyborgs and digitized consciousnesses.

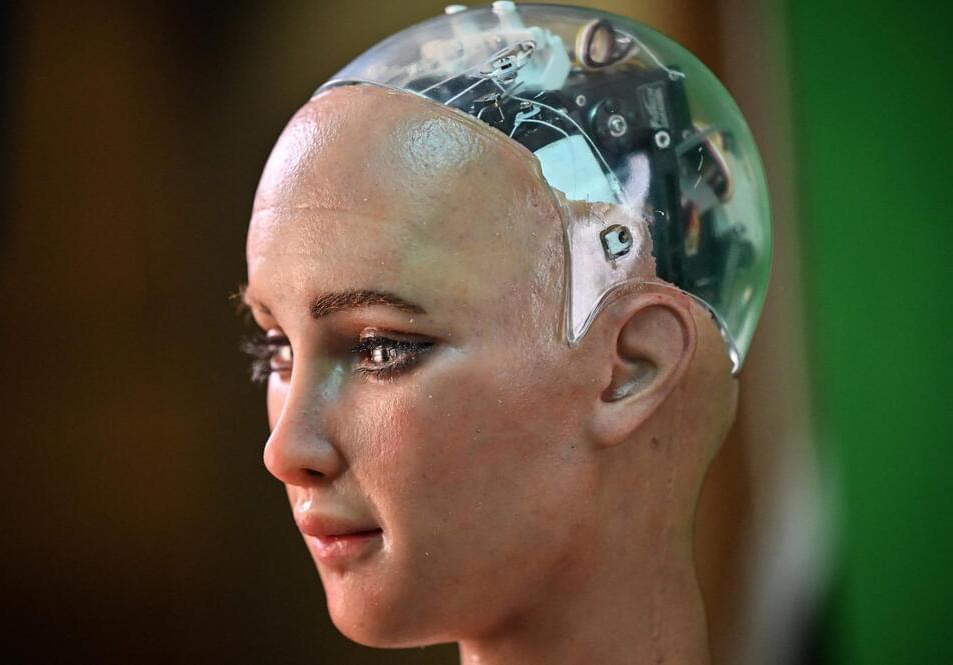

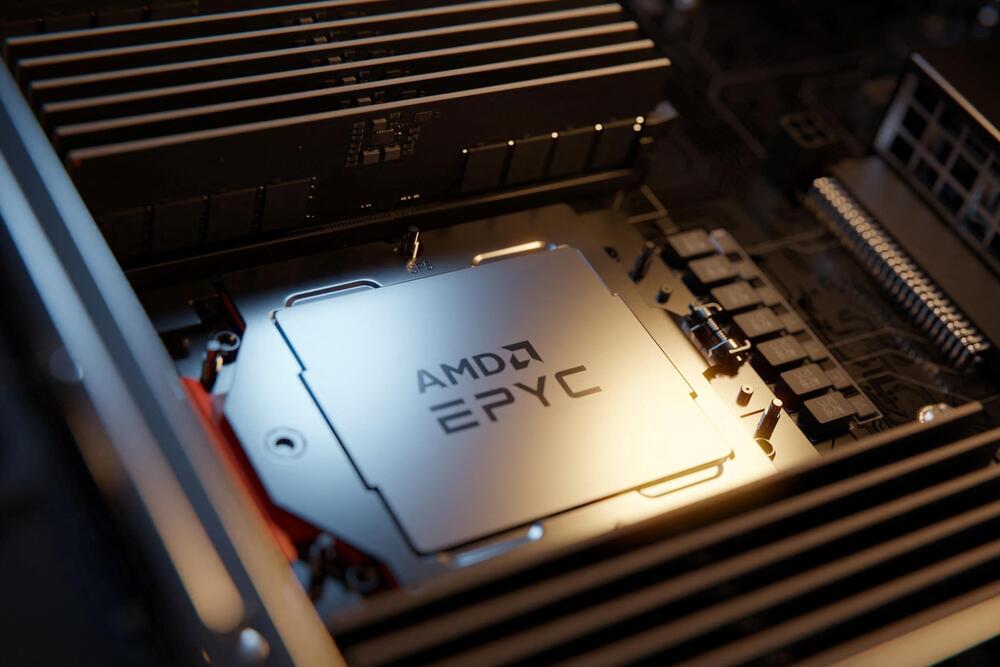

The traditional temporal scarcity argument against immortality imagines the human being remaining biologically the same as it has for tens of thousands of years. Yet the human race is already augmenting the human body with radical technology. Globally, over 200,000 people already have brain implants, and Silicon Valley companies like Elon Musk’s Neuralink are working on trying to get millions of us to become cyborgs.

A growing number of experts even believe by the end of the century, humans will likely have the ability to upload the brain and its consciousness into a computer. In the process, digitized people will overcome biological death and engage in far more complex ways of being, including grand new designs of consciousness and selfhood.