When it comes to understanding the mystery of human consciousness, scientists have long sought the hidden mechanism that transforms mere neural firing into the rich experience of thought.

Now, a leading MIT neuroscientist believes he’s found a clue that suggests the brain’s electrical waves don’t just reflect our thoughts, but actually create them.

At the Society for Neuroscience’s annual meeting on November 15, Dr. Earl K. Miller, a professor at MIT’s Picower Institute for Learning and Memory, will unveil a provocative proposal: that cognition and consciousness emerge from the fast, flexible organization of the brain’s cortex—powered by analog computations performed by traveling brain waves.

In other words, the rhythm of the brain may be more than background noise—it may be the very pulse of thought itself.

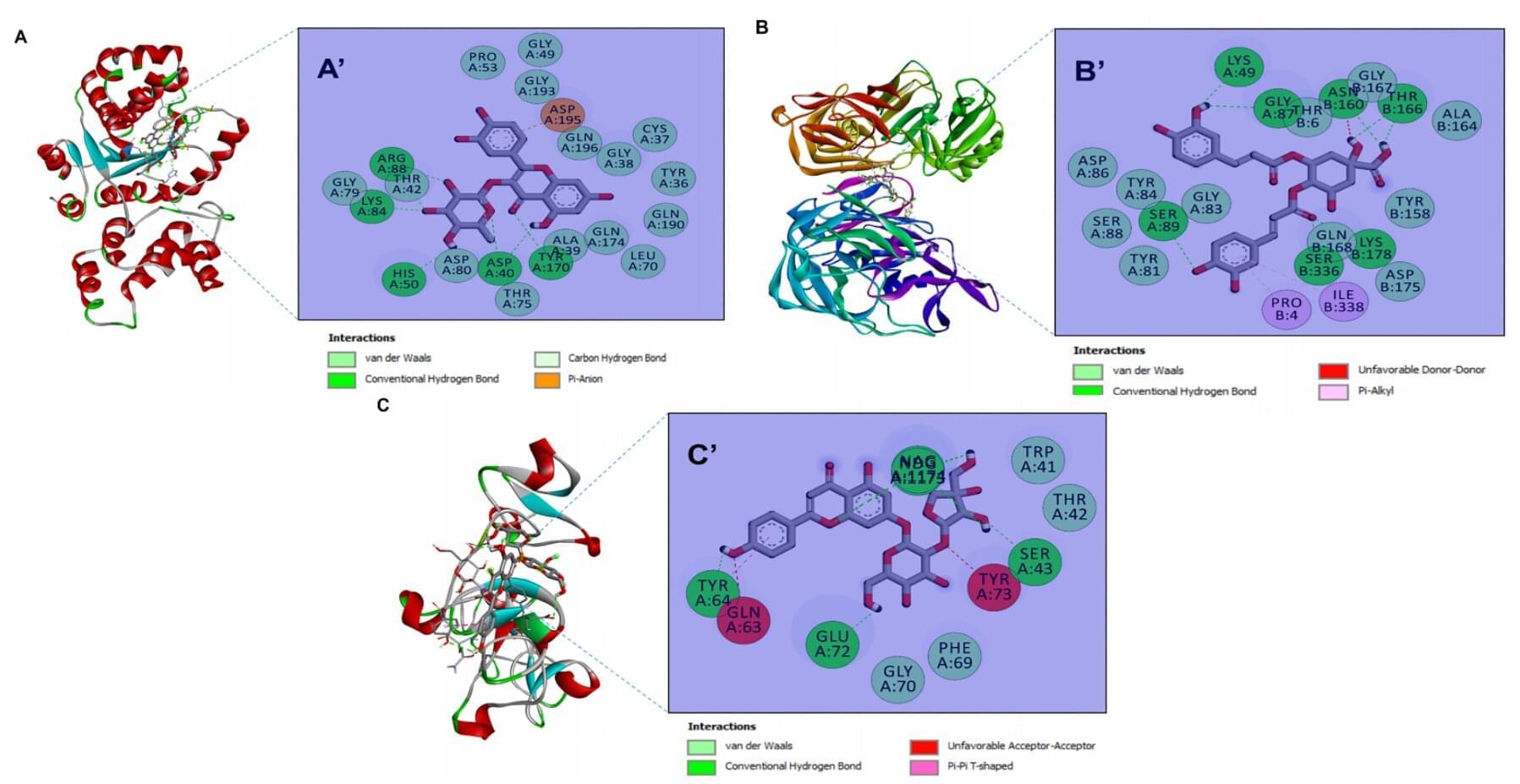

“The brain uses these oscillatory waves to organize itself,” Dr. Miller said in a press statement. “Cognition is large-scale neural self-organization. The brain has got to organize itself to perform complex behaviors. Brain waves are the patterns of excitation and inhibition that organize the brain, and this leads to consciousness because consciousness is this organized knitting together of the cortex.”

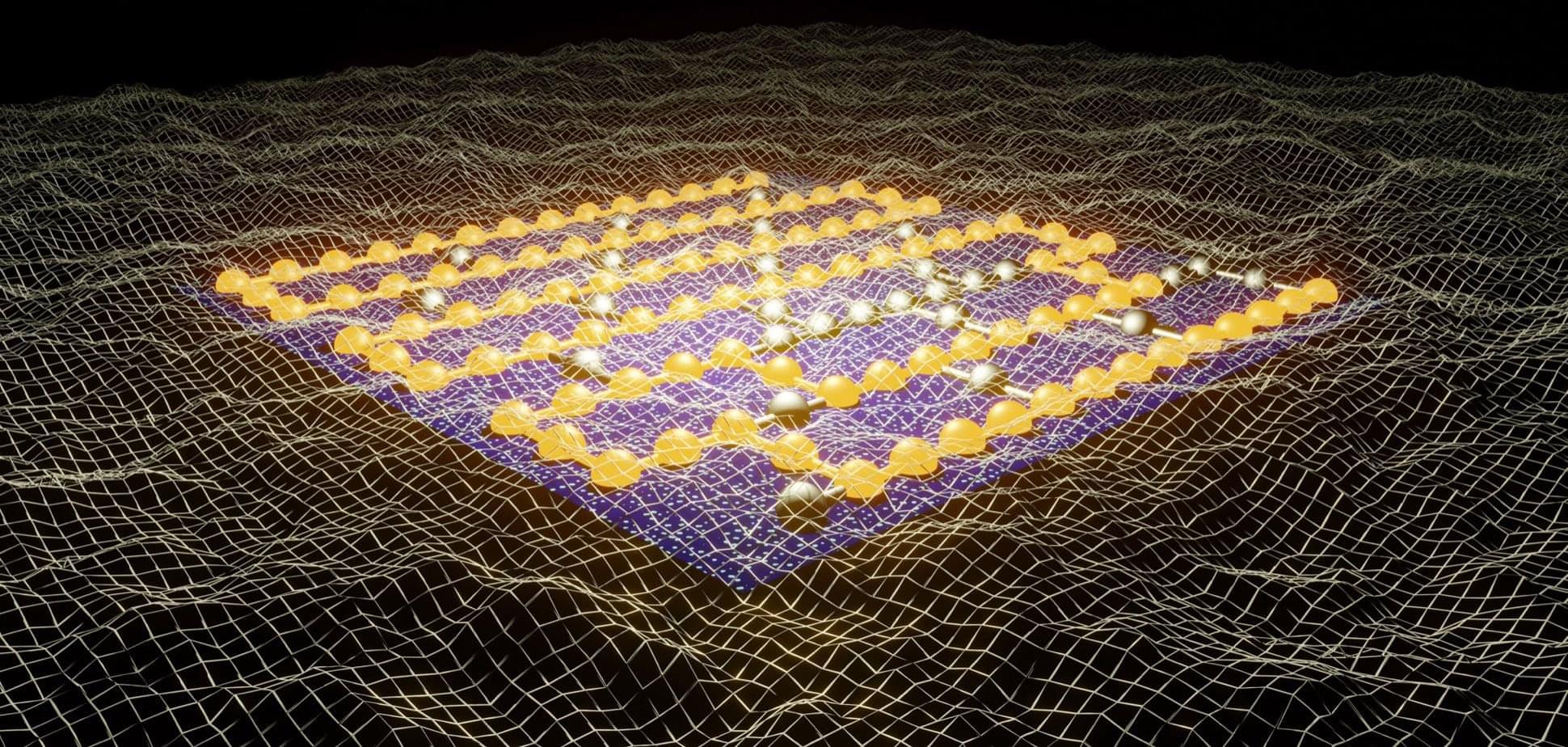

Dr. Miller’s theory revives the concept of analog computation. Unlike digital computers, which rely on discrete binary bits, analog systems process continuous information—waves interacting to produce a vast range of possible values.

Dr. Miller argues that the brain’s natural oscillations—electrical waves generated by millions of neurons—function as analog computers, sculpting information in a fast, flexible, and energy-efficient way.