This is the concept behind mind uploading – the idea that we may one day be able to transition a person from their biological body to a synthetic hardware. The idea originated in an intellectual movement called transhumanism and has several key advocates including computer scientist Ray Kurzweil, philosopher Nick Bostrom and neuroscientist Randal Koene.

The transhumanists’ central hope is to transcend the human condition through scientific and technological progress. They believe mind uploading may allow us to live as long as we want (but not necessarily forever). It might even let us improve ourselves, such as by having simulated brains that run faster and more efficiently than biological ones. It’s a techno-optimist’s dream for the future. But does it have any substance?

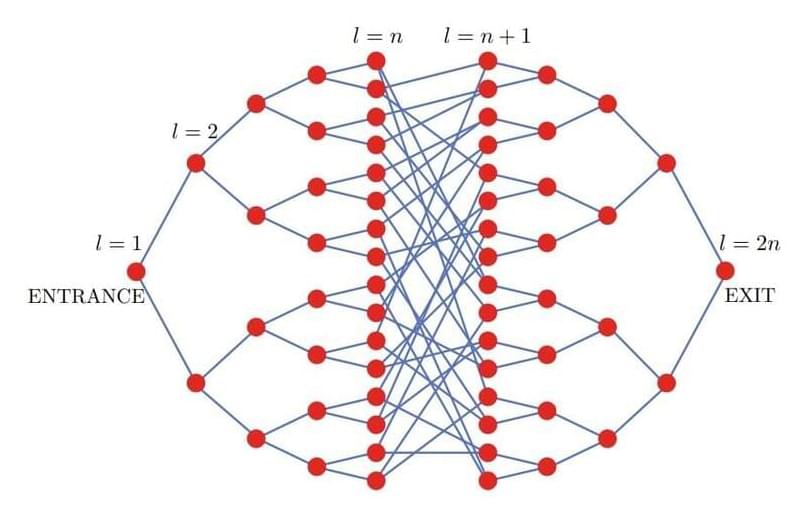

The feasibility of mind uploading rests on three core assumptions.