🔒 Keep Your Digital Life Private and Be Safe Online: https://nordvpn.com/safetyfirst…

Category: computing – Page 284

Deep-sea sponge’s ‘zero-energy’ flow control could inspire new energy efficient designs

Now, new research reveals yet another engineering feat of this ancient animal’s structure: its ability to filter feed using only the faint ambient currents of the ocean depths, no pumping required.

This discovery of natural ‘“zero energy” flow control by an international research team co-led by University of Rome Tor Vergata and NYU Tandon School of Engineering could help engineers design more efficient chemical reactors, air purification systems, heat exchangers, hydraulic systems, and aerodynamic surfaces.

In a study published in Physical Review Letters, the team found through extremely high-resolution computer simulations how the skeletal structure of the Venus flower basket sponge (Euplectella aspergillum) diverts very slow deep sea currents to flow upwards into its central body cavity, so it can feed on plankton and other marine detritus it filters out of the water.

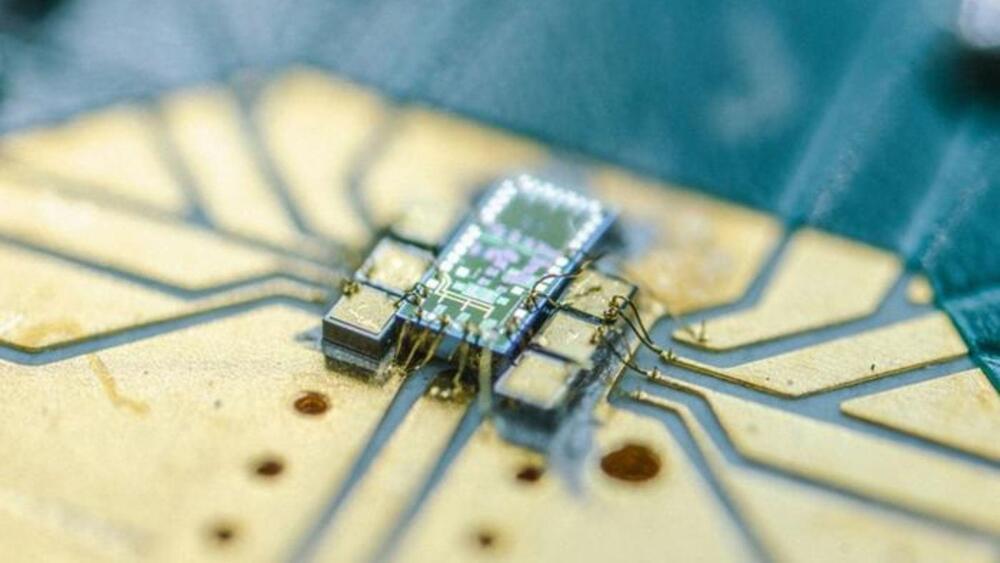

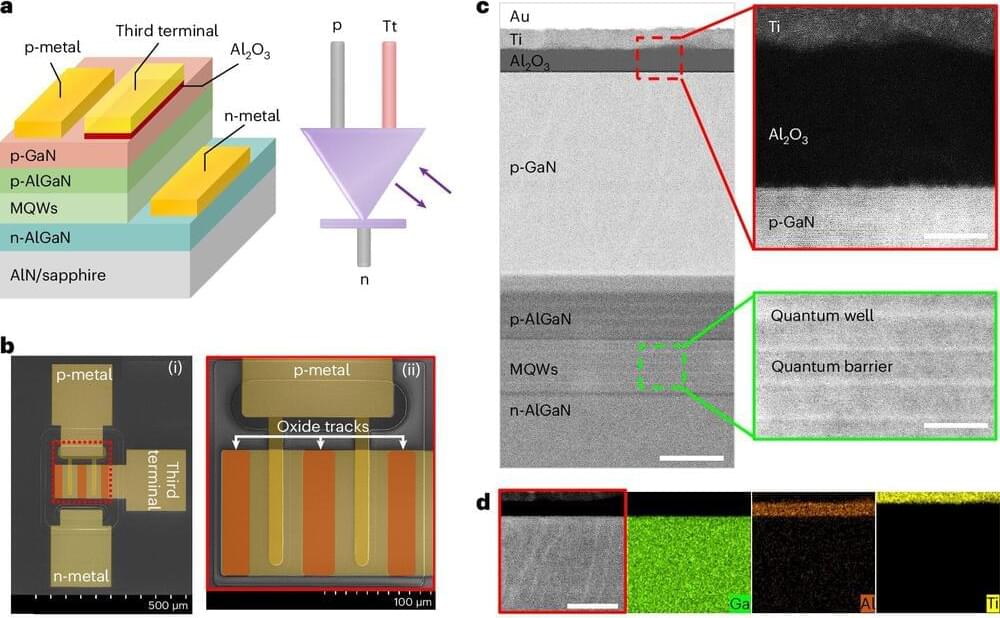

Researchers develop world’s smallest quantum light detector on a silicon chip

Researchers at the University of Bristol have made an important breakthrough in scaling quantum technology by integrating the world’s tiniest quantum light detector onto a silicon chip. The paper, “A Bi-CMOS electronic photonic integrated circuit quantum light detector,” was published in Science Advances.

Quantum Computers Take a Major Step With Error Correction Breakthrough

For quantum computers to go from research curiosities to practically useful devices, researchers need to get their errors under control. New research from Microsoft and Quantinuum has now taken a major step in that direction.

Today’s quantum computers are stuck firmly in the “noisy intermediate-scale quantum” (NISQ) era. While companies have had some success stringing large numbers of qubits together, they are highly susceptible to noise which can quickly degrade their quantum states. This makes it impossible to carry out computations with enough steps to be practically useful.

While some have claimed that these noisy devices could still be put to practical use, the consensus is that quantum error correction schemes will be vital for the full potential of the technology to be realized. But error correction is difficult in quantum computers because reading the quantum state of a qubit causes it to collapse.

How Quantum Computers Could Illuminate the Full Range of Human Genetic Diversity

Genomics is revolutionizing medicine and science, but current approaches still struggle to capture the breadth of human genetic diversity. Pangenomes that incorporate many people’s DNA could be the answer, and a new project thinks quantum computers will be a key enabler.

When the Human Genome Project published its first reference genome in 2001, it was based on DNA from just a handful of humans. While less than one percent of our DNA varies from person to person, this can still leave important gaps and limit what we can learn from genomic analyses.

That’s why the concept of a pangenome has become increasingly popular. This refers to a collection of genomic sequences from many different people that have been merged to cover a much greater range of human genetic possibilities.