Long read sequencing technology (advanced by Pacific Biosciences (PacBio) and Oxford Nanopore Technologies (Nanopore)) is revolutionizing the genomics field [43] and it has major potential to be a powerful computational tool for investigating the telomere length variation within populations and between species. Read length from long read sequencing platforms is orders of magnitude longer than short read sequencing platforms (tens of kilobase pairs versus 100–300 bp). These long reads have greatly aided in resolving the complex and highly repetitive regions of the genome [44], and near gapless genome assemblies (also known as telomere-to-telomere assembly) are generated for multiple organisms [45, 46]. The long read sequences can also be used for estimating telomere length, since whole genome sequencing using a long read sequencing platform would contain reads that span the entire telomere and subtelomere region. Computational methods can then be developed to determine the telomere–subtelomere boundary and use it to estimate the telomere length. As an example, telomere-to-telomere assemblies have been used for estimating telomere length by analyzing the sequences at the start and end of the gapless chromosome assembly [47,48,49,50]. But generating gapless genome assemblies is resource intensive and cannot be used for estimating the telomeres of multiple individuals. Alternatively, methods such as TLD [51], Telogator [52], and TeloNum [53] analyze raw long read sequences to estimate telomere lengths. These methods require a known telomere repeat sequence but this can be determined through k-mer based analysis [54]. Specialized methods have also been developed to concentrate long reads originating from chromosome ends. These methods involve attaching sequencing adapters that are complementary to the single-stranded 3′ G-overhang of the telomere, which can subsequently be used for selectively amplifying the chromosome ends for long read sequencing [55,56,57,58]. While these methods can enrich telomeric long reads, they require optimization of the protocol (e.g., designing the adapter sequence to target the G-overhang) and organisms with naturally blunt-ended telomeres [59, 60] would have difficulty implementing the methods.

An explosion of long read sequencing data has been generated for many organisms across the animal and plant kingdom [61, 62]. A computational method that can use this abundant long read sequencing data and estimate telomere length with minimal requirements can be a powerful toolkit for investigating the biology of telomere length variation. But so far, such a method is not available, and implementing one would require addressing two major algorithmic considerations before it can be widely used across many different organisms. The first algorithmic consideration is the ability to analyze the diverse telomere sequence variation across the tree of life. All vertebrates have an identical telomere repeat motif TTAGGG [63] and most previous long read sequencing based computational methods were largely designed for analyzing human genomic datasets where the algorithms are optimized on the TTAGGG telomere motif. But the telomere repeat motif is highly diverse across the animal and plant kingdom [64,65,66,67], and there are even species in fungi and plants that utilize a mix of repeat motifs, resulting in a sequence complex telomere structure [64, 68, 69]. A new computational method would need to accommodate the diverse telomere repeat motifs, especially across the inherently noisy and error-prone long read sequencing data [70]. With recent improvements in sequencing chemistry and technology (HiFi sequencing for PacBio and Q20 + Chemistry kit for Nanopore) error rates have been substantially reduced to 1% [71, 72]. But even with this low error rate, a telomeric region that is several kilobase pairs long can harbor substantial erroneous sequences across the read [73] and hinder the identification of the correct telomere–subtelomere boundary. In addition, long read sequencers are especially error-prone to repetitive homopolymer sequences [74,75,76], and the GT-rich microsatellite telomere sequences are predicted to be an especially erroneous region for long read sequencing. A second algorithmic consideration relates to identifying the telomere–subtelomere boundary. Prior long read sequencing based methods [51, 52] have used sliding windows to calculate summary statistics and a threshold to determine the boundary between the telomere and subtelomere. Sliding window and threshold based analyses are commonly used in genome analysis, but they place the burden on the user to determine the appropriate cutoff, which for telomere length measuring computational methods may differ depending on the sequenced organism. In addition, threshold based sliding window scans can inflate both false positive and false negative results [77,78,79,80,81,82] if the cutoff is improperly determined.

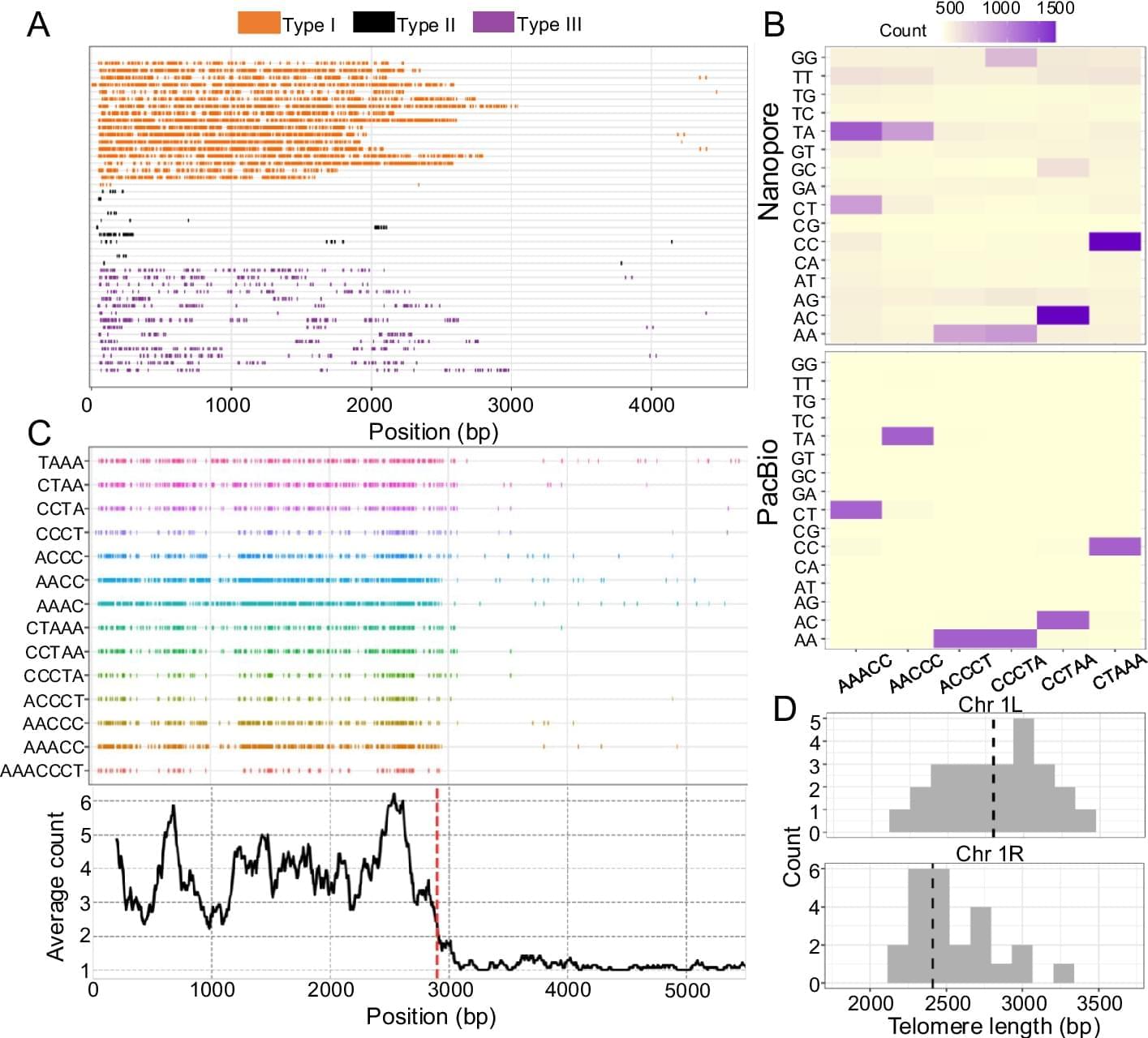

Here, we introduce Topsicle, a computational method that uses a novel strategy to estimate telomere lengths from raw long read sequences from the entire whole genome sequencing library. Methodologically, Topsicle iterates through different substring sizes of the telomere repeat sequence (i.e., telomere k-mer) and different phases of the telomere k-mer are used to summarize the telomere repeat content of each sequencing read. The k-mer based summary statistics of telomere repeats are then used for selecting long reads originating from telomeric regions. Topsicle uses those putative reads from the telomere region to estimate the telomere length by determining the telomere–subtelomere boundary through a binary segmentation change point detection analysis [83]. We demonstrate the high accuracy of Topsicle through simulations and apply our new method on long read sequencing datasets from three evolutionarily diverse plant species (A. thaliana, maize, and Mimulus) and human cancer cell lines. We believe using Topsicle will enable high-resolution explorations of telomere length for more species and achieve a broad understanding of the genetics and evolution underlying telomere length variation.