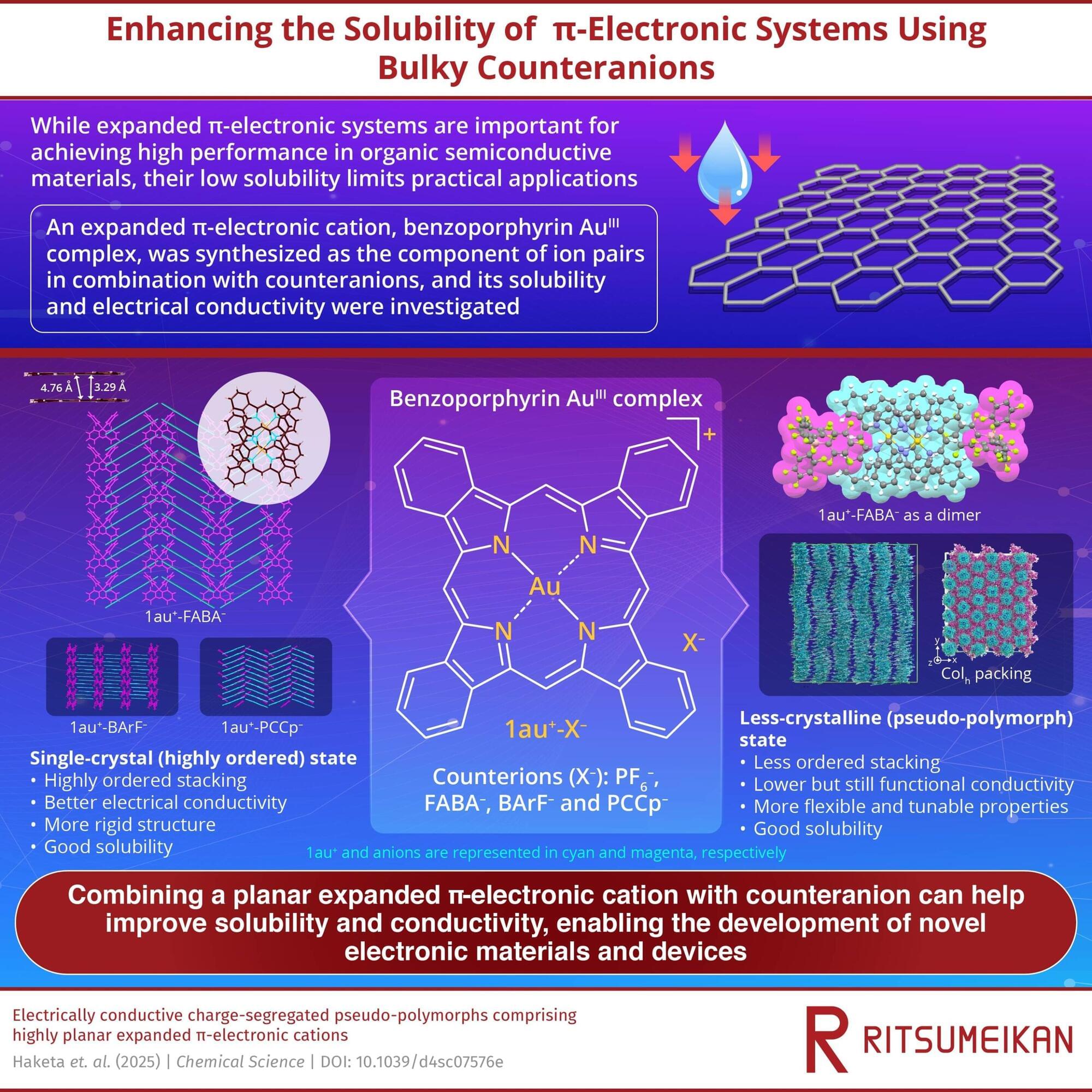

Unsubstituted π-electronic systems with expanded π-planes are highly desirable for improving charge-carrier transport in organic semiconductors. However, their poor solubility and high crystallinity pose major challenges in processing and assembly, despite their favorable electronic properties. The strategic arrangement of these molecular structures is crucial for achieving high-performance organic semiconductive materials.

In a significant breakthrough, a research team led by Professor Hiromitsu Maeda from Ritsumeikan University, including Associate Professor Yohei Haketa from Ritsumeikan University, Professor Shu Seki from Kyoto University, and Professor Go Watanabe from Kitasato University, has synthesized a novel organic electronic system incorporating gold (AuIII) and benzoporphyrin molecules, enabling enhanced solubility and conductivity.

The findings of the study were published online in Chemical Science.