Scientific Reports volume 15, Article number: 42,309 (2025) Cite this article.

Scientific Reports volume 15, Article number: 42,309 (2025) Cite this article.

Researchers have found that they could use highly insulating aluminum-coated polymer film to improve the performance of flexible electronics and medical sensors.

Currently, the aluminum-coated polymer film is used to shield satellites from temperature extremes.

Researchers at Empa have succeeded in making the material even more resistant by implementing an ultra-thin intermediate layer.

On a Sunday evening earlier this month, a Stanford professor held a salon at her home near the university’s campus. The main topic for the event was “synthesizing consciousness through neuroscience,” and the home filled with dozens of people, including artificial intelligence researchers, doctors, neuroscientists, philosophers and a former monk, eager to discuss the current collision between new AI and biological tools and how we might identify the arrival of a digital consciousness.

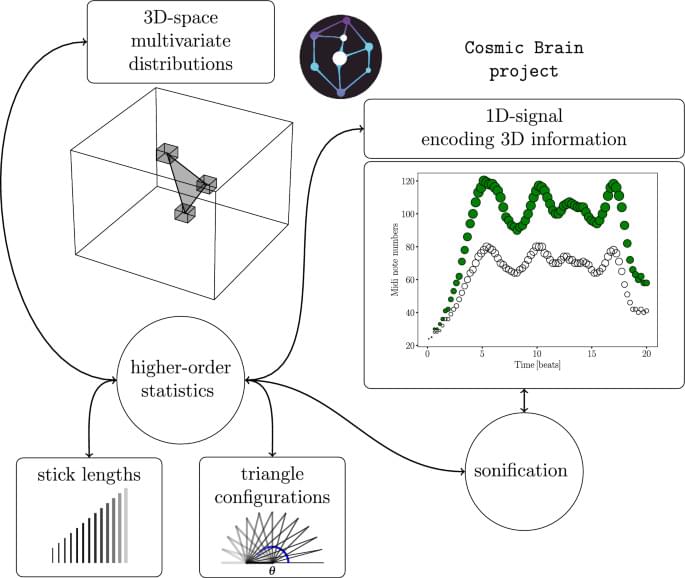

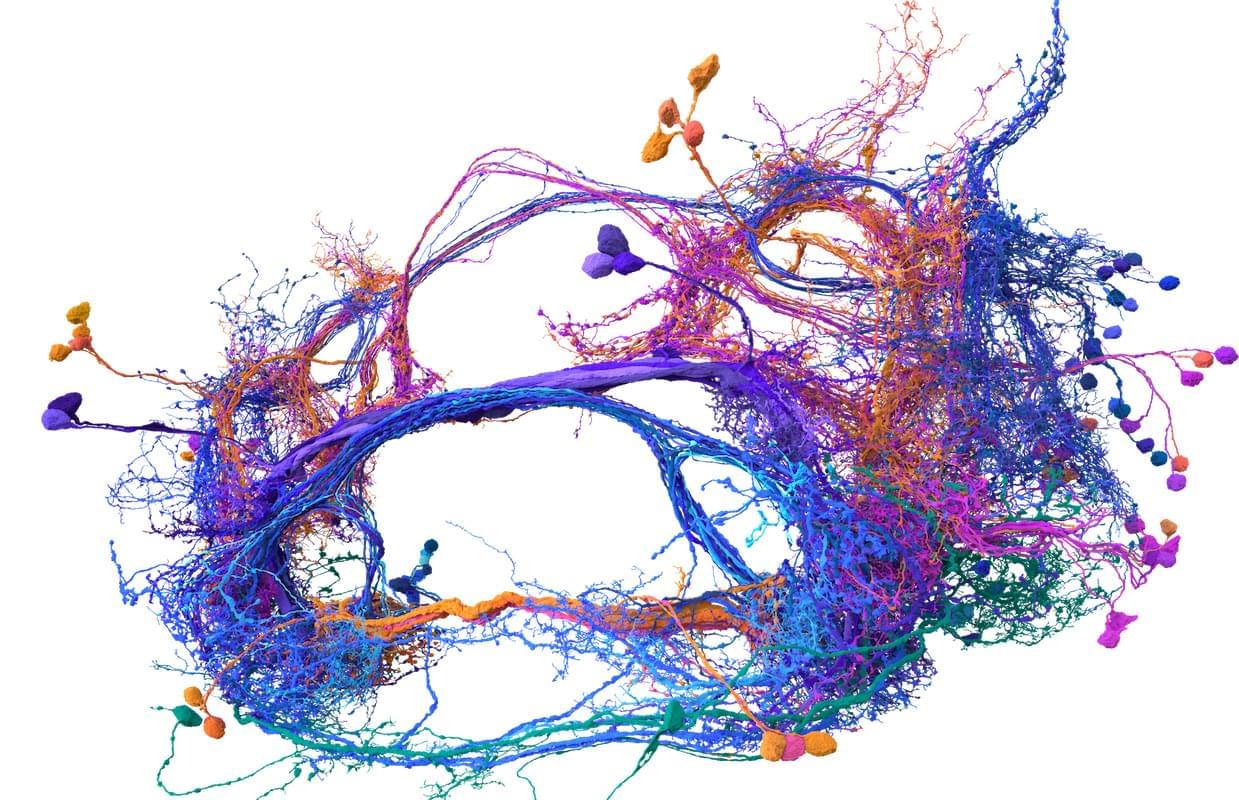

The opening speaker for the salon was Sebastian Seung, and this made a lot of sense. Seung, a neuroscience and computer science professor at Princeton University, has spent much of the last year enjoying the afterglow of his (and others’) breakthrough research describing the inner workings of the fly brain. Seung, you see, helped create the first complete wiring diagram of a fly brain and its 140,000 neurons and 55 million synapses. (Nature put out a special issue last October to document the achievement and its implications.) This diagram, known as a connectome, took more than a decade to finish and stands as the most detailed look at the most complex whole brain ever produced.

Meet Memazing.

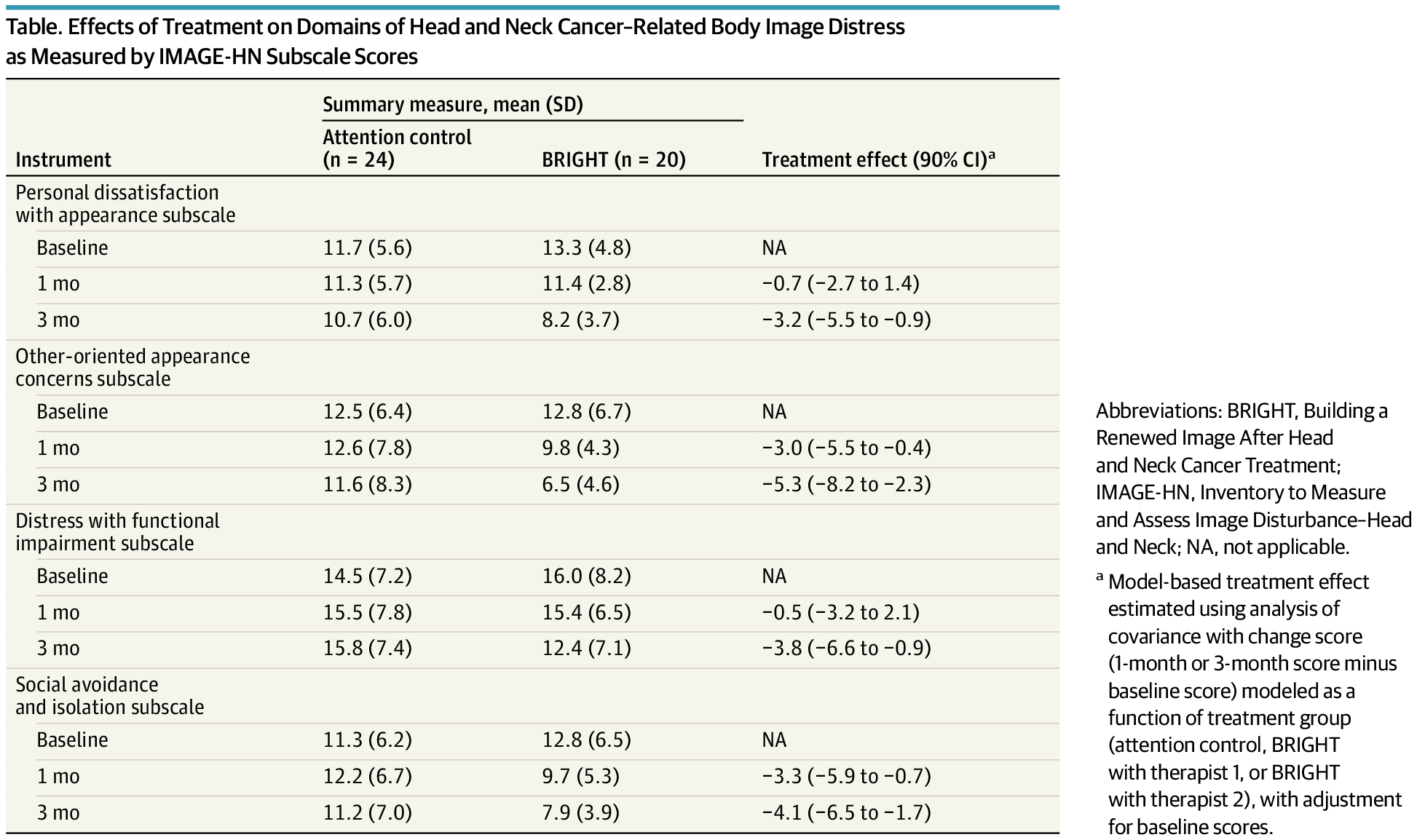

The BRIGHT program, a brief cognitive behavioral treatment, effectively reduced body image distress across multiple domains in head and neck cancer survivors.

This secondary analysis of a randomized clinical trial evaluates whether a brief, tailored cognitive behavioral treatment program is effective across multiple domains of head and neck cancer–related body image distress.

A new study from the MRC Laboratory of Medical Sciences (LMS) in London, UK reveals how ancient viral DNA once written off as “junk” plays a crucial role in the earliest moments of life. The research, published in Science Advances, begins to untangle the role of an ancient viral DNA element called MERVL in mouse embryonic development and provides new insights into a human muscle wasting disease.

Transposable elements are stretches of DNA that can move around the genome. Many of these DNA sequences originate from long ago, when viruses inserted their genetic material into our ancestors’ genomes during infection. Today, these viral transposable elements make up around 8–10% of the mammalian genome.

Once disregarded as “junk” DNA, we now know that many transposable elements play an important role in influencing how genes are turned on and off, especially during early development. They have a variety of beneficial and harmful roles in the body, for example, some help regulate normal immune responses, while others can disrupt genes and contribute to diseases like cancer.

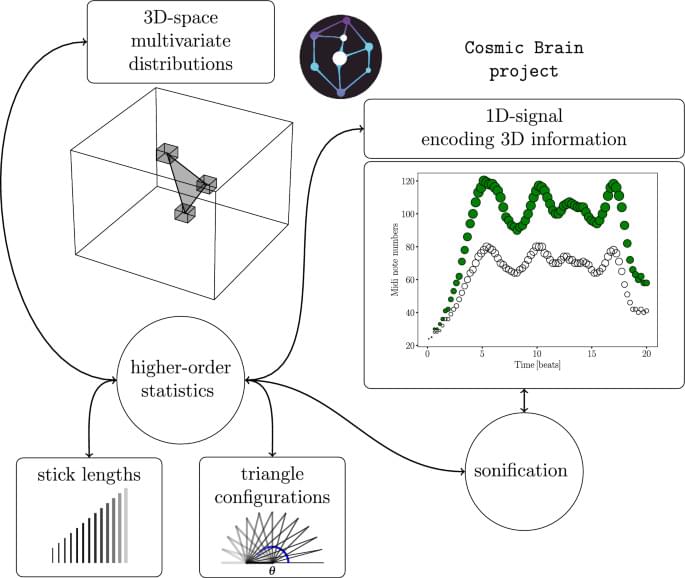

Epigenetic clocks, based on DNA methylation profiles at CpG sites, are widely recognized as reliable biomarkers of biological aging. However, common single-nucleotide polymorphisms (cSNPs), genomic variants that can overlap CpG sites, may affect DNA methylation profiles in ways that potentially interfere with the accuracy of epigenetic clocks. Moreover, because the prevalence of cSNPs varies across populations, such cSNP-CpG overlaps may differentially affect the age predictions of epigenetic clocks in diverse cohorts. Here, we present the first systematic cross-ancestry evaluation of cSNP robustness in the epigenetic clock, examining how cSNP-CpG overlaps affect the performance of epigenetic clocks across nine major genomic ancestry groups. We employed three complementary strategies: (a) testing whether cSNP-CpG overlaps are overrepresented in established epigenetic clocks or particular populations, (b) evaluating whether overlapping CpG sites correspond to the most influential aging predictors within clock models, and © simulating the effects of cSNP-associated methylation changes on predicted biological age. Our findings indicate that cSNP-CpG overlaps are not enriched among the CpG sites used in current epigenetic clocks, nor do they tend to involve the most influential sites. Furthermore, our simulation analysis revealed that current epigenetic clocks appear robust to cSNP-related methylation variations. Our findings underscore the overall stability of current epigenetic clocks, even in the presence of population-specific cSNP-CpG overlaps that are known to affect DNA methylation levels.

The authors have declared no competing interest.

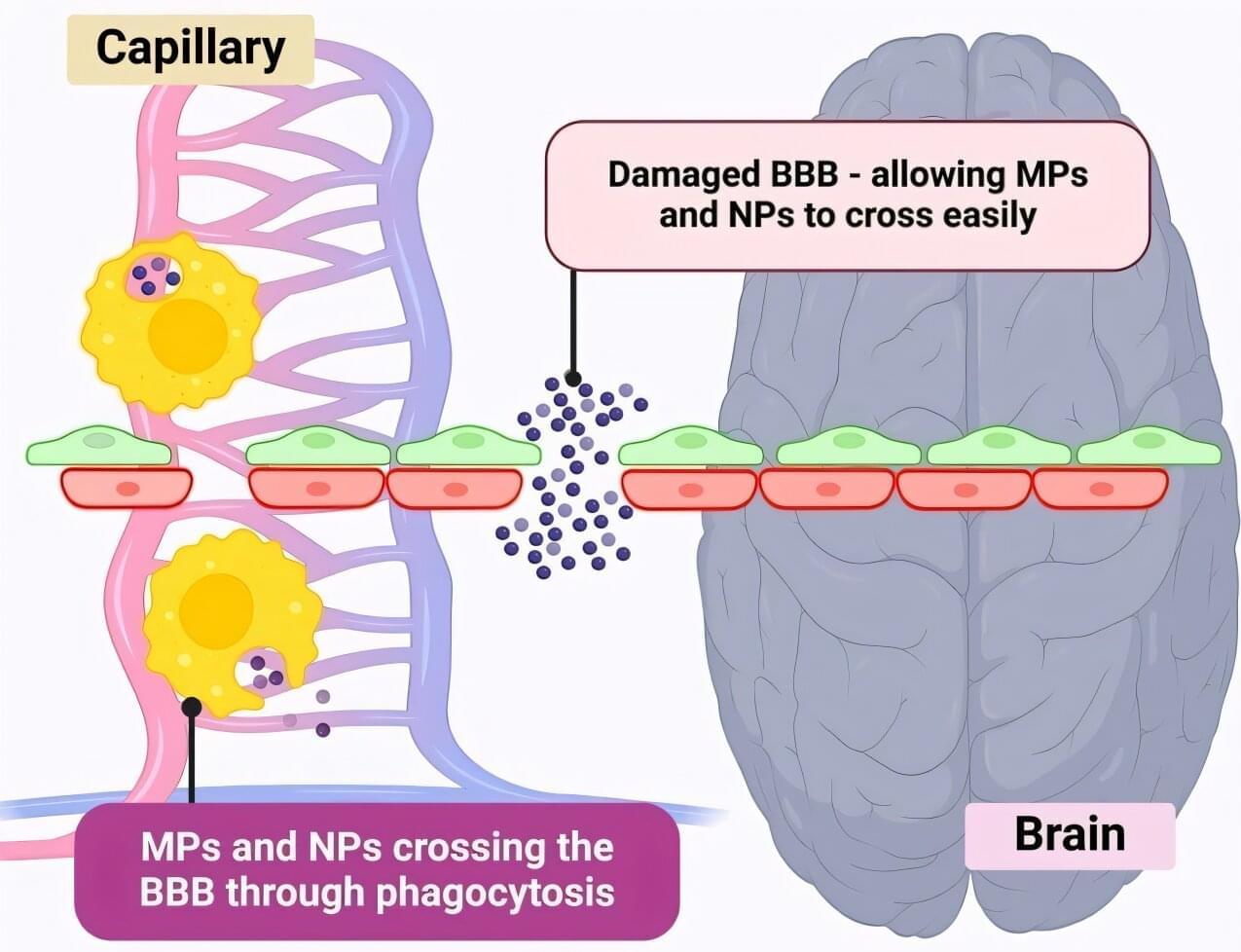

Microplastics could be fueling neurodegenerative diseases like Alzheimer’s and Parkinson’s, with a new study highlighting five ways microplastics can trigger inflammation and damage in the brain.

More than 57 million people live with dementia, and cases of Alzheimer’s and Parkinson’s are projected to rise sharply. The possibility that microplastics could aggravate or accelerate these brain diseases is a major public health concern.

Pharmaceutical scientist Associate Professor Kamal Dua, from the University of Technology Sydney, said it is estimated that adults are consuming 250 grams of microplastics every year—enough to cover a dinner plate.

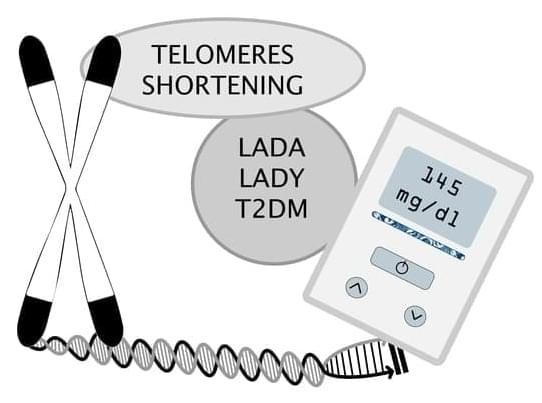

This study aimed to explore the role of telomere length in three different diabetes types: latent autoimmune diabetes of adulthood (LADA), latent autoimmune diabetes in the young (LADY), and type 2 diabetes mellitus (T2DM). A total of 115 patients were included, 72 (62.61%) had LADA, 30 (26.09%) had T2DM, and 13 (11.30%) had LADY. Telomere length was measured using real-time Polymerase Chain Reaction. For statistical analysis, we used the ANOVA test, X2 test, and the Mann–Whitney U test. Patients with T2DM had higher BMI compared to LADA and LADY groups, with a BMI average of 31.32 kg/m2 (p = 0.0235). While the LADA group had more patients with comorbidities, there was not a statistically significant difference (p = 0.3164, p = 0.3315, p = 0.3742 for each of the previously mentioned conditions).

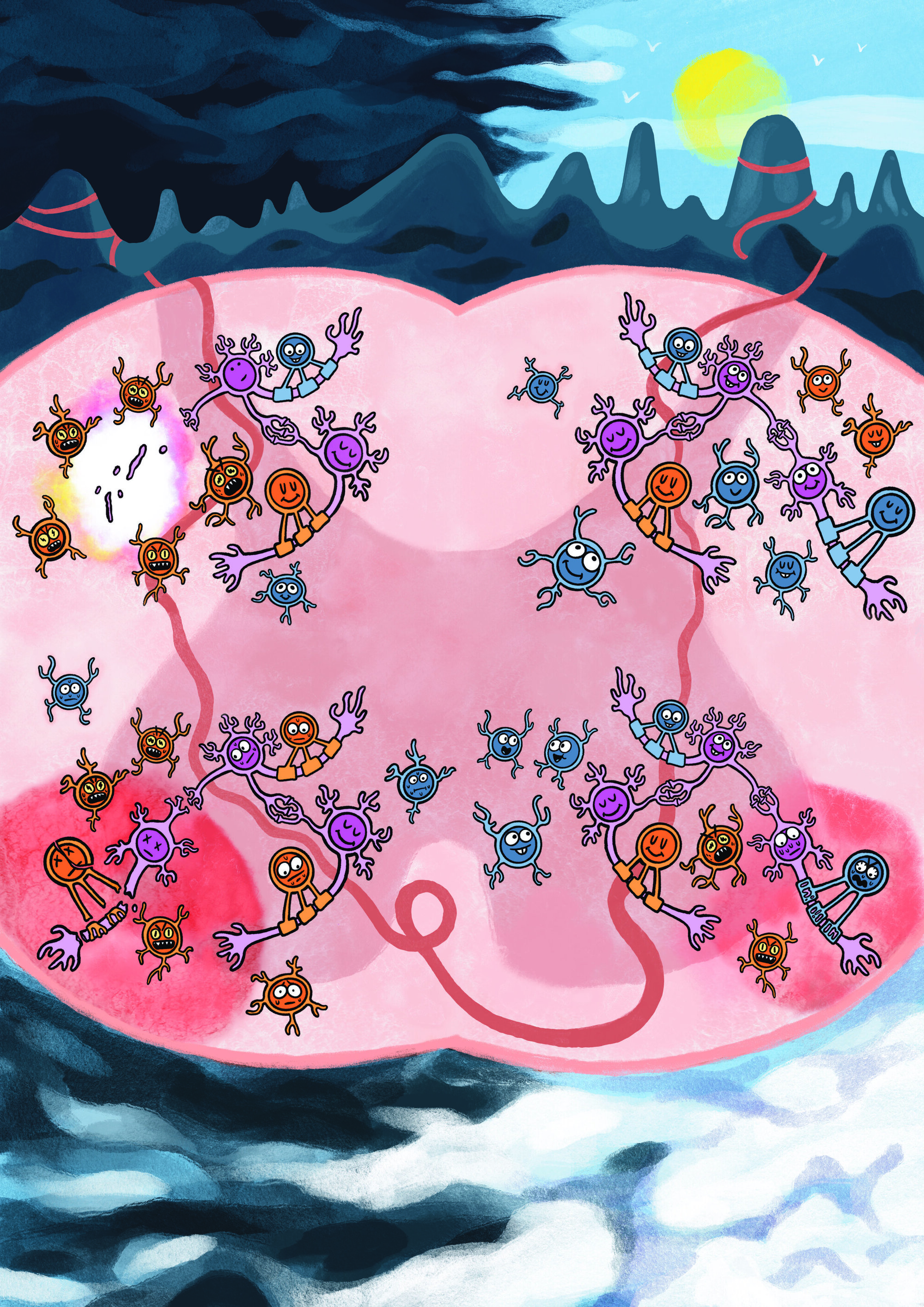

Multiple sclerosis (MS) is a chronic autoimmune disease characterized by the disruption of nerve signals and various associated neurological symptoms, ranging from vision problems to numbness, weakness, fatigue and cognitive impairments. These symptoms emerge when the immune system starts to attack mature oligodendrocytes (MOLs), specialized cells that produce the protective sheath surrounding nerve fibers (i.e., myelin).

There are several subtypes of MOLs, which might exhibit different immune cell-like genetic responses in patients diagnosed with MS. While various studies have investigated the neural and molecular underpinnings of MS, how these different cell subtypes respond as the disease progresses has not yet been elucidated.

Researchers at Karolinska Institute in Sweden recently carried out a mouse study aimed at mapping how different MOL subtypes might differ in their sensitivity to neuroinflammation across different stages of MS.