Over the recent decades, comprehensive genome-wide association studies (GWAS) have indicated the potential influence of genetic factors on one’s alcohol consumption volume and identified over 100 related variants6,7. However, a predominant proportion of the identified variants are localized within noncoding regions, and their effect sizes tend to be small, making interpretation and identification of the causal gene challenging8. In addition, previous GWAS mainly utilized imputed genotype data, which only cover limited regions of the genome, and thus may have missed many potential genes. Furthermore, GWAS studies focused mainly on common variants, and few studies have investigated rare variants associated with alcohol consumption, which yield greater potential to interpret biological function and elucidate mechanisms9. Although there are studies that have attempted to leverage exome chip data to identify rare variants contributing to alcohol consumption, the sample size was small and limited regions of the whole exome were examined10.

The introduction of whole exome sequencing (WES) provides a great chance to overcome the limitations of previous genetic studies on alcohol consumption with a substantially larger amount of rare and ultra-rare protein-coding variants11,12,13. Collapsing of loss-of-function (LOF) variants helps estimate the effect direction of associated genes13,14. When combined with large-scale population cohorts with multi-modal phenotypic data, WES would greatly facilitate our understanding of the genetic underpinnings of alcohol consumption as well as its implication on physical and mental health6. However, to our knowledge, there have been few large-scale WES studies on alcohol consumption, let alone elucidating the potential implications of the identified genes10,15. Meanwhile, as indicated by a previous genome-wide association study, significant genetic associations existed between alcohol consumption and several body health phenotypes7. The application of phenome-wide analysis for alcohol-related genes can help extend and deepen our current comprehension of the association between alcohol consumption and human health.

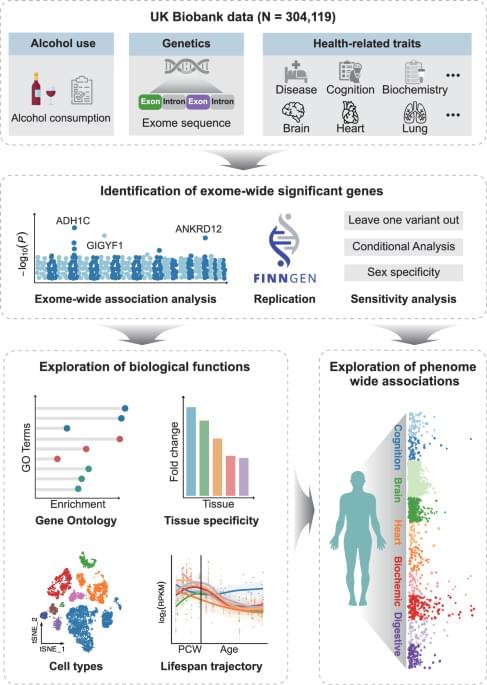

Hence, aiming to refine the genetic architecture of alcohol consumption, we conduct an exome-wide association study (ExWAS) for alcohol consumption among 304,119 individuals from the UK Biobank (UKB). We also examine the rare-variant associations with genes reported by previous GWAS6,7,16,17. Finally, we provide biological insights into the identified genes via bioinformatics analyses and phenome-wide association analysis (PheWAS).