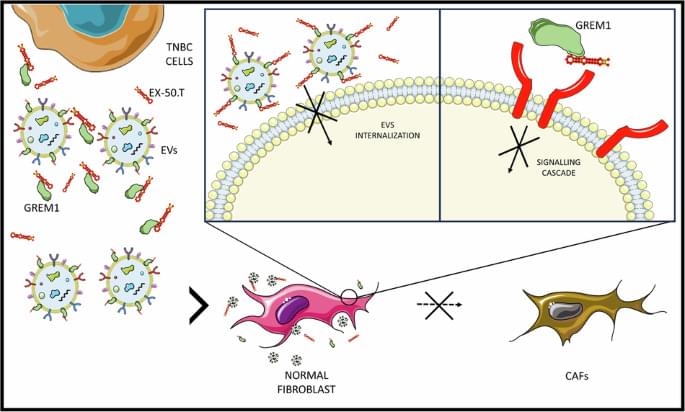

Quintavalle, C., Ingenito, F., Roscigno, G. et al. Ex.50.T aptamer impairs tumor–stroma cross-talk in breast cancer by targeting gremlin-1. Cell Death Discov. 11, 94 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41420-025-02363-6

Quintavalle, C., Ingenito, F., Roscigno, G. et al. Ex.50.T aptamer impairs tumor–stroma cross-talk in breast cancer by targeting gremlin-1. Cell Death Discov. 11, 94 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41420-025-02363-6

As people age, these cells become defective and lose their ability to renew and repair the blood system, decreasing the body’s ability to fight infections as seen in older adults. Another example is a condition called clonal hematopoiesis; this asymptomatic condition is considered a premalignant state that increases the risk of developing blood cancers and other inflammatory disorders. Its prevalence increases significantly with age.

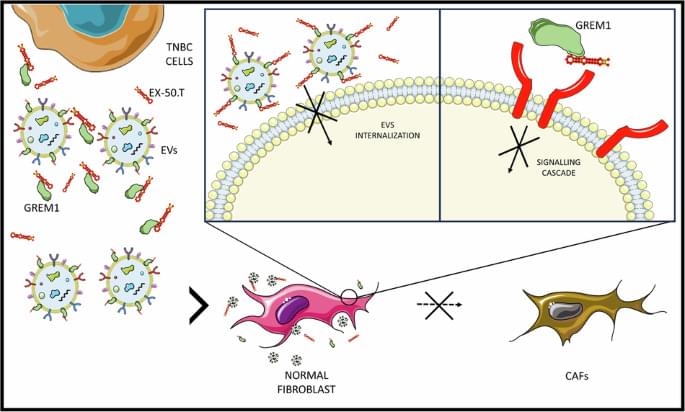

The team discovered that lysosomes in aged HSCs become hyper-acidic, depleted, damaged, and abnormally activated, disrupting the cells’ metabolic and epigenetic stability. Using single-cell transcriptomics and stringent functional assays, the researchers found that suppressing this hyperactivation with a specific vacuolar ATPase inhibitor restored lysosomal integrity and blood-forming stem cell function.

The old stem cells started acting young and healthy once more. Old stem cells regained their regenerative potential and ability to be transplanted and to produce more healthy stem cells and blood that is balanced in immune cells; they renewed their metabolism and mitochondrial function, improved their epigenome, reduced their inflammation, and stopped sending out “inflammation” signals that can cause damage in the body.

Remarkably, ex vivo treatment (when cells are removed from the body, modified in a laboratory, and returned to the body) of old stem cells with the lysosomal inhibitor boosted their in vivo blood-forming capacity more than eightfold, demonstrating that correcting lysosomal dysfunction can restore regenerative potential.

This restoration also dampened harmful inflammatory and interferon-driven pathways by improving lysosomal processing of mitochondrial DNA and reducing activation of the cGAS-STING immune signaling pathway, which they find to be a key driver of inflammation and aging of stem cells.

Researchers have discovered how to reverse aging in blood-forming stem cells in mice by correcting defects in the stem cell’s lysosomes. The breakthrough, published in Cell Stem Cell, identifies lysosomal hyperactivation and dysfunction as key drivers of stem cell aging and shows that restoring lysosomal slow degradation can revitalize aged stem cells and enhance their regenerative capacity.

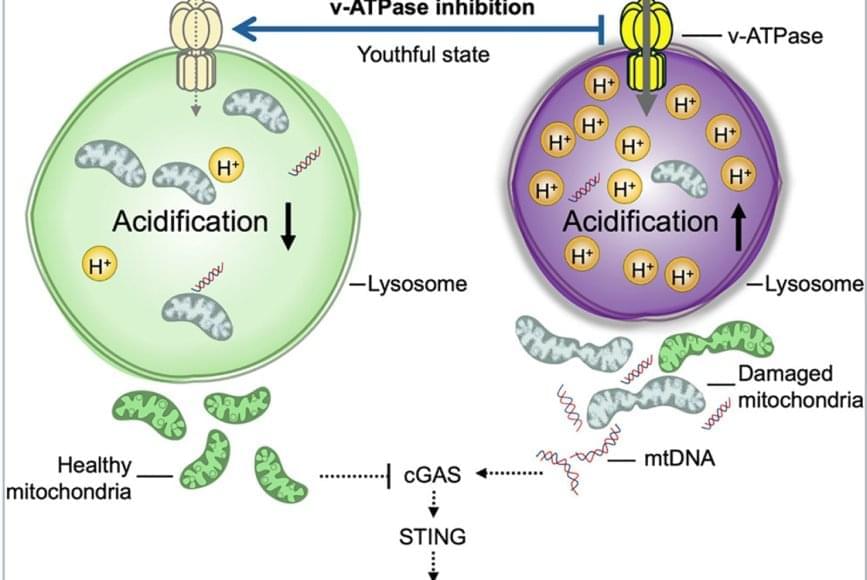

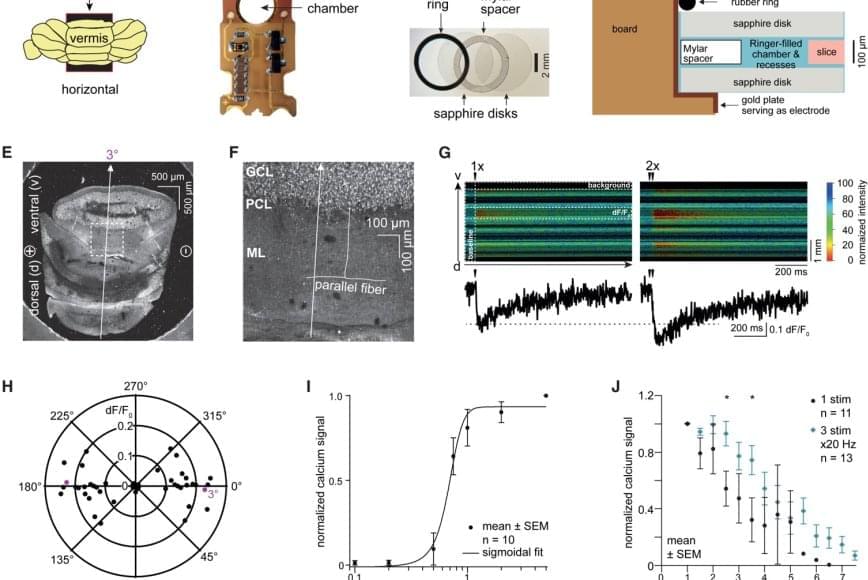

For the new study, the researchers used samples from the brains of normal mice as well as living cortical brain tissue sampled with permission from six individuals undergoing surgical treatment for epilepsy. The surgical procedures were medically necessary to remove lesions from the brain’s hippocampus.

The researchers first validated the zap-and-freeze approach by observing calcium signaling, a process that triggers neurons to release neurotransmitters in living mouse brain tissues.

Next, the scientists stimulated neurons in mouse brain tissue with the zap-and-freeze approach and observed where synaptic vesicles fuse with brain cell membranes and then release chemicals called neurotransmitters that reach other brain cells. The scientists then observed how mouse brain cells recycle synaptic vesicles after they are used for neuronal communication, a process known as endocytosis that allows material to be taken up by neurons.

The researchers then applied the zap-and-freeze technique to brain tissue samples from people with epilepsy, and observed the same synaptic vesicle recycling pathway operating in human neurons.

In both mouse and human brain samples, the protein Dynamin1xA, which is essential for ultrafast synaptic membrane recycling, was present where endocytosis is thought to occur on the membrane of the synapse.

“Our findings indicate that the molecular mechanism of ultrafast endocytosis is conserved between mice and human brain tissues,” the author says, suggesting that the investigations in these models are valuable for understanding human biology.

Cancer treatment with a cell-based immunotherapy causes mild cognitive impairment, a Stanford Medicine team found. They also identified compounds that could treat it.

In a patient from a histoplasmosis-endemic region, laryngeal histoplasmosis caused by Histoplasma capsulatum was diagnosed after biopsy revealed granulomatous inflammation and fungal organisms.

Early consideration and biopsy are key when evaluating ulcerative laryngeal lesions.

A 61-year-old man presented to the otolaryngology clinic with a 2-month history of progressive hoarseness, dysphagia, odynophagia, and persistent globus sensation. What is your diagnosis?