Despite the initial excitement and flashy headlines, all of these early ventures failed or switched focus away from aging. Most of these companies and their backers underestimated the complexity, costs, and time it would take to discover and develop a drug. Recent estimates suggest that developing a new drug takes over https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/abs/pii/S1359644623002428” rel=“noopener”>10 years and costs upwards of $6.1 billion and the failure rates exceed 90%. This figure reflects the immense difficulty of identifying therapeutic targets, conducting preclinical and clinical trials, and navigating the regulatory landscape. When it comes to developing a drug specifically for aging, the challenges multiply, making it much more difficult to design effective interventions and demonstrate their efficacy in clinical trials.

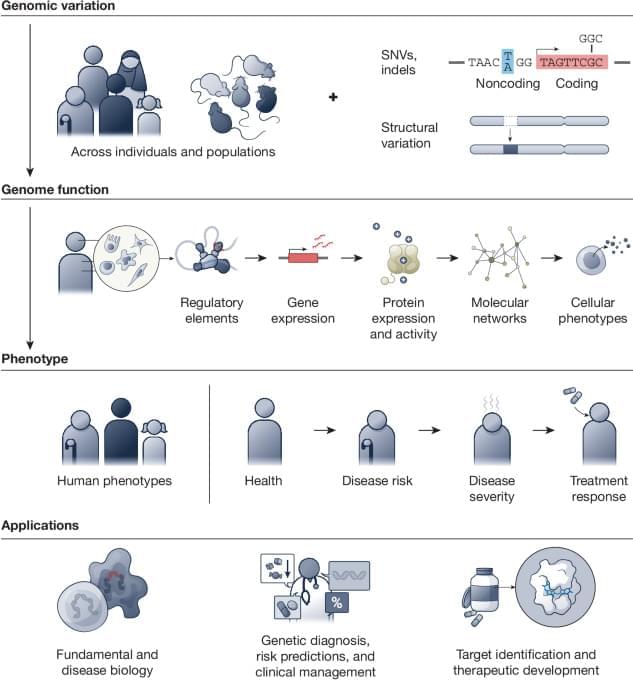

Fast forward to today, and a new generation of longevity biotechnology companies with a more conservative approach than their predecessors has emerged. Companies like http://www.bioagelabs.com” rel=“noopener”>BioAge Labs and http://www.insilico.com” rel=“noopener”>Insilico Medicine are using artificial intelligence (AI) to discover drugs that target specific chronic diseases or biological processes closely associated with aging. Instead of trying to develop therapies for aging directly, these companies focus on conditions that are closely linked to the aging process like obesity, muscle wasting, fibrosis, anemia, and even cancer… The strategy is to develop drugs for these diseases that could later be repurposed to address aging more broadly. And while in the technology industry we try to focus on moving very fast to win, here we prepare to play a very long game and focus on resilience and novelty rather than putting all eggs in one basket and failing miserably like dozens of companies in the past three decades.