Scientists found a compound that appears to counter common mutations behind POLG-related diseases, rare conditions that harm mitochondrial DNA.

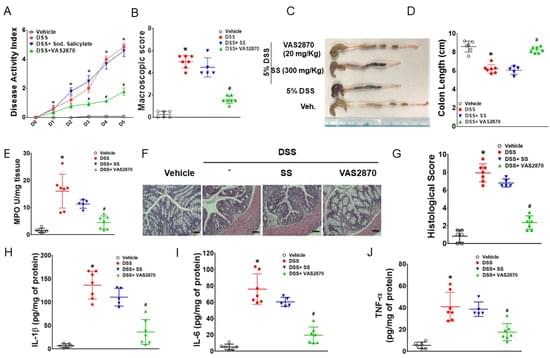

Macrophage adenosine monophosphate-activated protein kinase (AMPK) limits the development of experimental colitis. AMPK activation inhibits NADPH oxidase (NOX) 2 expression, reactive oxygen species (ROS) generation, and pro-inflammatory cytokine secretion in macrophages during inflammation, while increased NOX2 expression is reported in experimental models of colitis and inflammatory bowel disease (IBD) patients. Although there are reductions in AMPK activity in IBD, it remains unclear whether targeted inhibition of NOX2 in the presence of defective AMPK can reduce the severity of colitis. Here, we investigate whether the inhibition of NOX2 ameliorates colitis in mice independent of AMPK activation. Our study identified that VAS2870 (a pan-Nox inhibitor) alleviated dextran sodium sulfate (DSS)-induced colitis in macrophage-specific AMPKβ1-deficient (AMPKβ1LysM) mice.

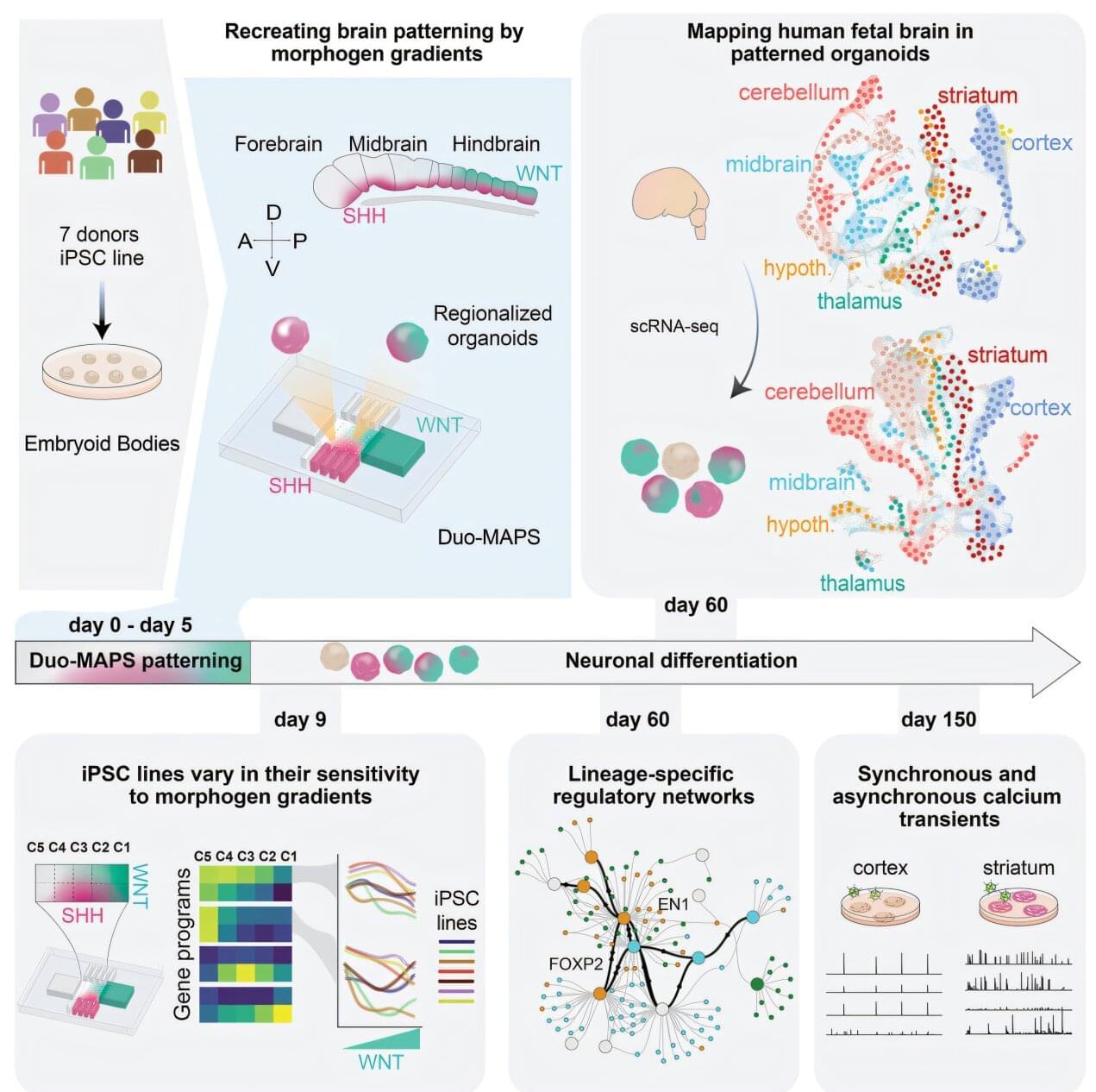

Just a few weeks after conception, stem cells are already orchestrating the future structure of the human brain. A new Yale-led study shows that, early in development, molecular “traffic cops” known as morphogens regulate the activation of gene programs that initiate stem cells’ differentiation into more specialized brain cells.

The Yale team found that sensitivity to these signaling morphogens can vary not only between stem cells from different donors, but between stem cells derived from the same individual.

“This is a new chapter in understanding how we develop and how development can be influenced by genomic changes between people and by epigenetic modifications within individuals,” said Flora Vaccarino, the Harris Professor in the Child Study Center at the Yale School of Medicine (YSM) and co-senior author of the research, published in the journal Cell Stem Cell.

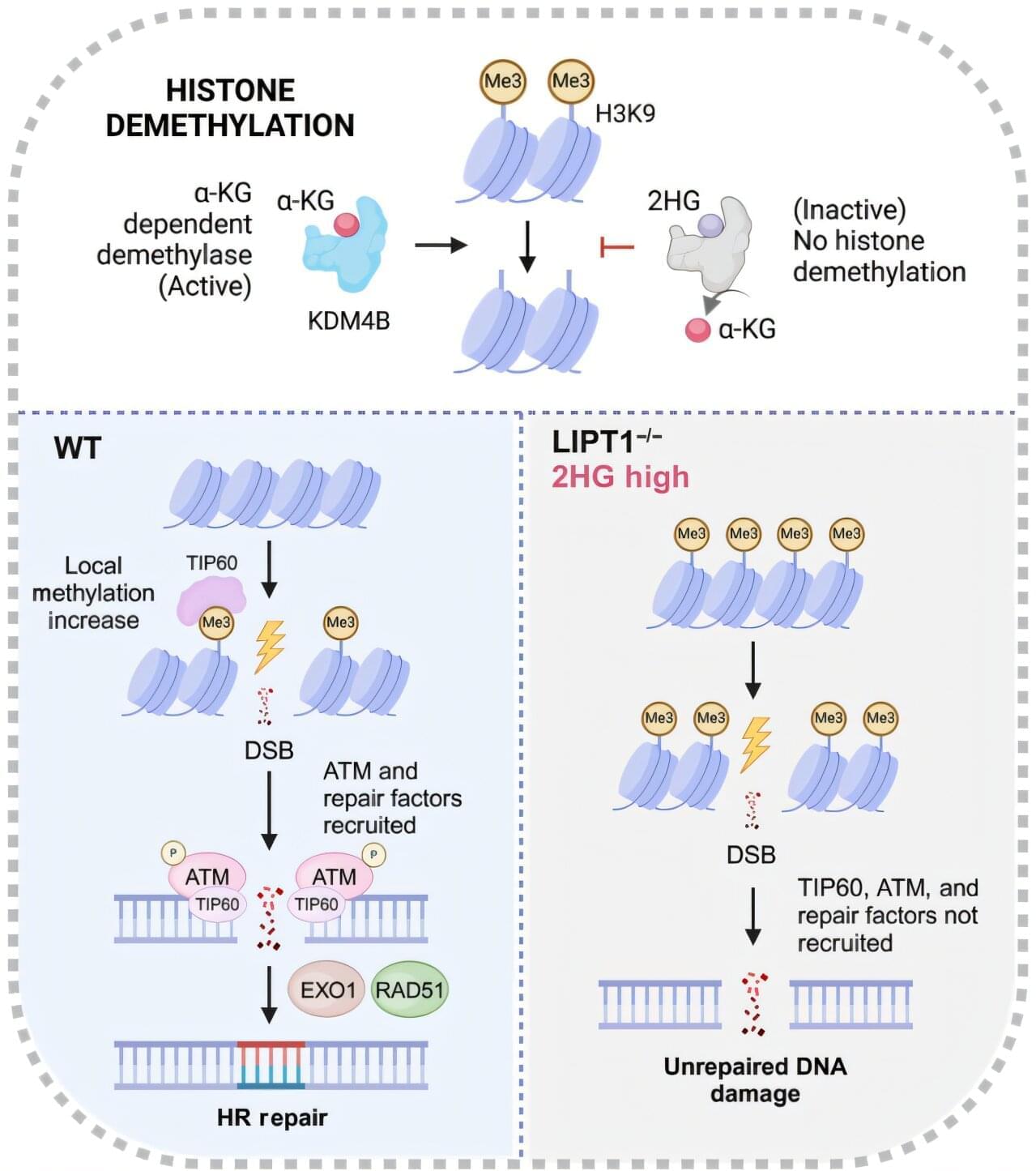

An FDA-designated orphan drug that can target a key vulnerability in lung cancer shows promise in improving the efficacy of radiation treatments in preclinical models, according to a study by UT Southwestern Medical Center researchers. The findings, published in Science Advances, suggest a new way to enhance the response to radiotherapy by inhibiting DNA repair in lung cancer cells.

“This study was motivated by challenges faced by millions of cancer patients undergoing radiation therapy, where treatment-related toxicities limit both curative potential and the patient’s quality of life,” said principal investigator Yuanyuan Zhang, M.D., Ph.D., Assistant Professor of Radiation Oncology and a member of the Harold C. Simmons Comprehensive Cancer Center at UT Southwestern.

Prior research, including from the laboratory of co-investigator Ralph J. DeBerardinis, M.D., Ph.D., Professor and Director of the Eugene McDermott Center for Human Growth and Development, Professor in Children’s Medical Center Research Institute at UT Southwestern, and co-leader of the Cellular Networks in Cancer Research Program in the Simmons Cancer Center, has demonstrated that altered metabolic pathways in lung cancer cells allow them to survive, grow, and spread. But the role of metabolism in enhancing radiation efficacy has not been thoroughly explored.

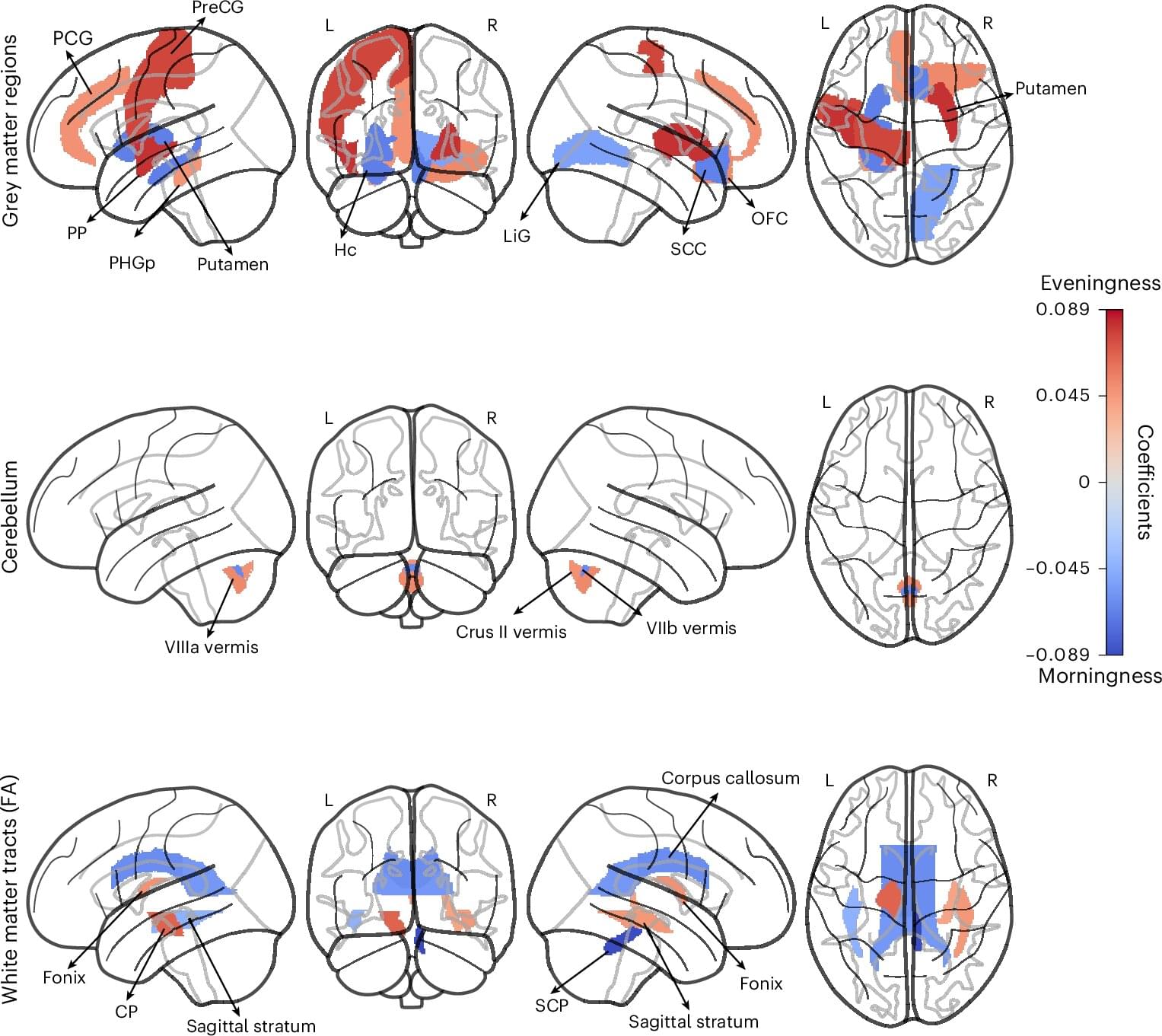

Human beings exhibit marked differences in habits, lifestyles and behavioral tendencies. One of these differences, known as chronotype, is the inclination to sleep and wake up early or alternatively to sleep and wake up late.

Changes in society, such as the introduction of portable devices and video streaming services, may have also influenced people’s behavioral patterns, offering them further distractions that could occupy their evenings or late nights. Yet past studies have found that sleeping and waking up late is often linked to a higher risk of being diagnosed with mental health disorders, such as depression and anxiety disorders, as well as poorer physical health.

Understanding the neurobiological underpinnings of humans’ chronotypes, as well as the possible implications of being a so-called “morning person” or “night owl,” could thus be beneficial. Specifically, it could inform the development of lifestyle interventions or medical treatments designed to promote healthy sleeping patterns.

A specialized model used by researchers is becoming a valuable tool for studying human brain development, diseases and potential treatments, according to a team of scientists at Rutgers University-New Brunswick.

Known as chimeric brain models, these laboratory tools provide a unique way to understand human brain functions in a living environment, which may lead to new and better therapies for brain disorders, researchers said in a review article in Neuron.

Scientists create models by transplanting human brain cells culled from stem cells into the brains of animals such as mice, thereby creating a mix of human and animal brain cells in the same brain. This environment is closer to the complexity of a living human brain than what can be simulated in a petri dish study.

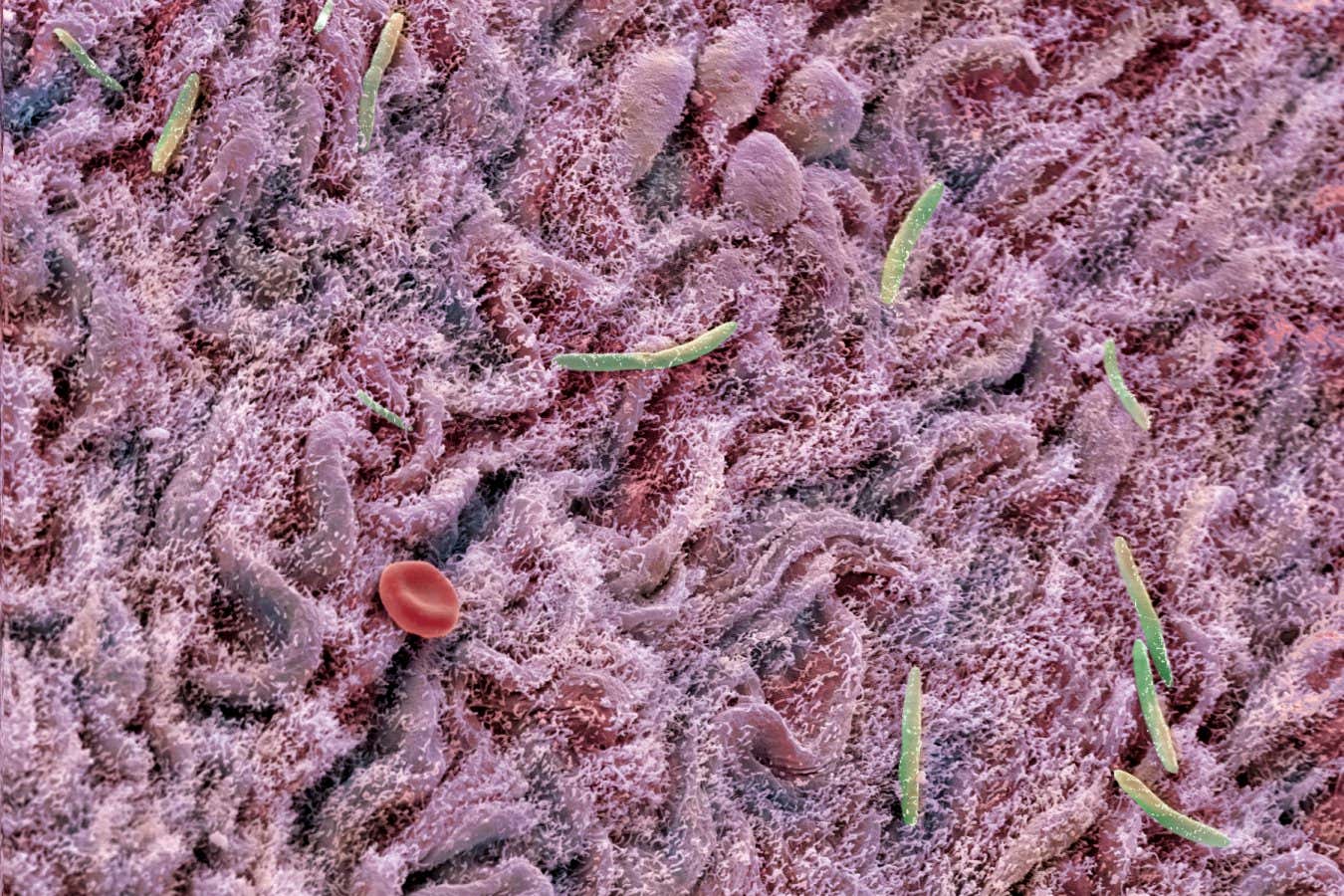

A team led by Rice University bioscientist Caroline Ajo-Franklin has discovered how certain bacteria breathe by generating electricity, using a natural process that pushes electrons into their surroundings instead of breathing on oxygen.

The findings, published in Cell, could enable new developments in clean energy and industrial biotechnology.

By identifying how these bacteria expel electrons externally, the researchers offer a glimpse into a previously hidden strategy of bacterial life. This work, which merges biology with electrochemistry, lays the groundwork for future technologies that harness the unique capabilities of these microscopic organisms.