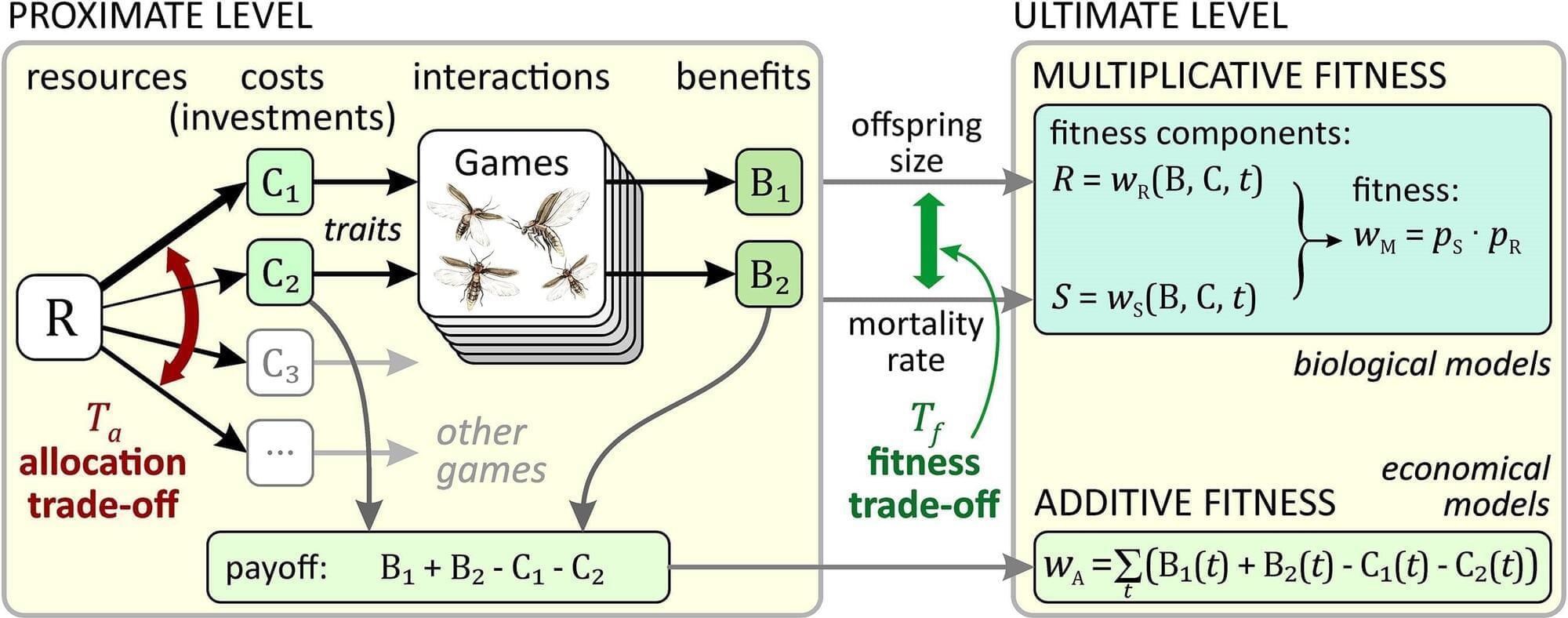

Here, Lintao Qu & team illuminate a neuroimmune mechanism in a mouse gout model involving MRGPRX2 signaling in synovial mast cells that drives pain and joint inflammation:

The figure: Mouse knee joint sections show treatment with an antibody against neuropeptide substance P (SP) decreases infiltration of neutrophils (Ly6G) and macrophages (CD68) into the synovium (S) in gout arthritis compared with control.

5Department of Endocrinology, Second Affiliated Hospital, University of South China, Hengyang, Hunan, China.

6College of Pharmacy, Rady Faculty of Health Sciences, University of Manitoba, Winnipeg, Manitoba, Canada.

7Center of Research Excellence in Allergy and Immunology, Research Department, Faculty of Medicine Siriraj Hospital, Mahidol University, Bangkok, Thailand.