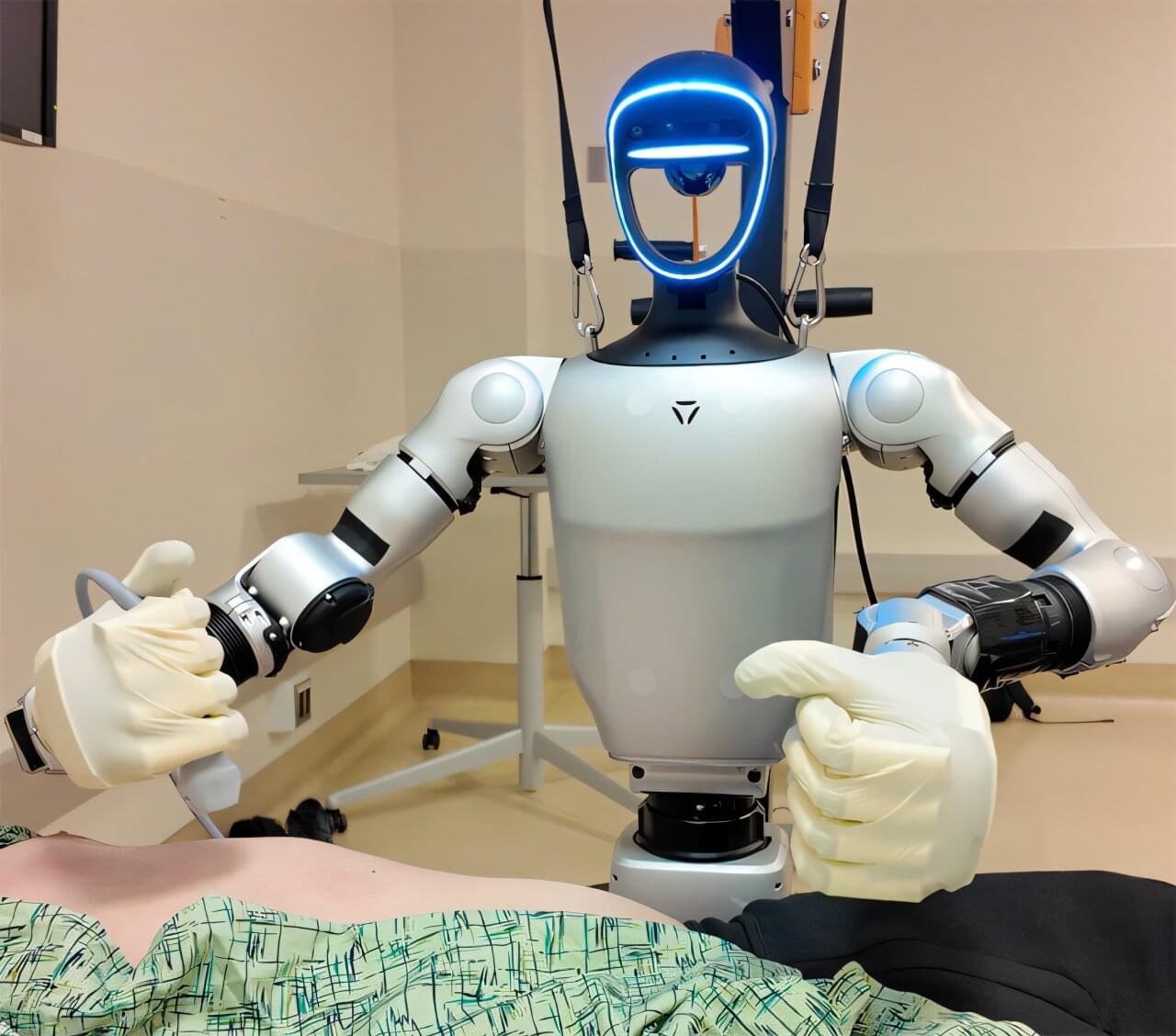

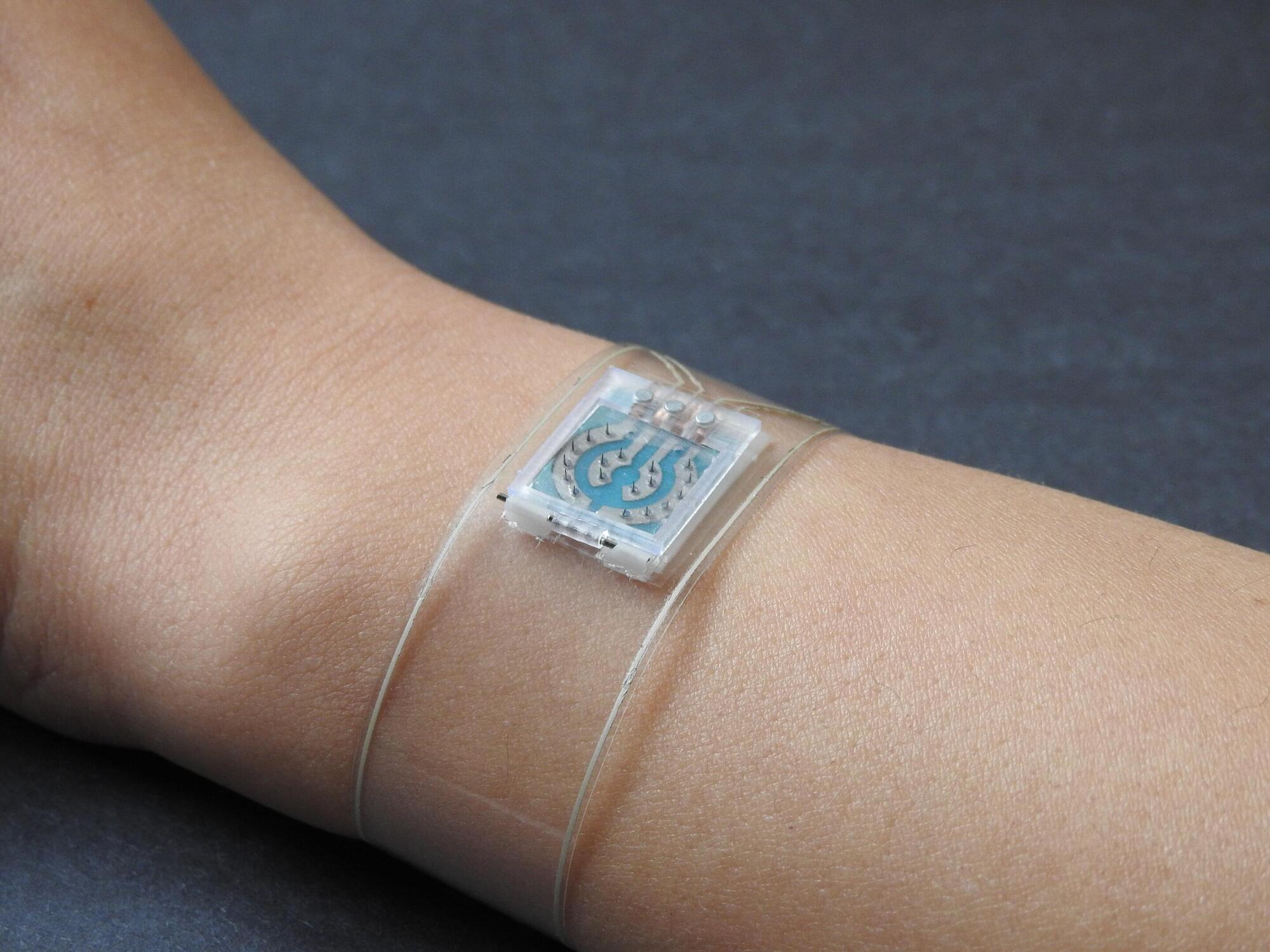

As waiting rooms fill up, doctors get increasingly burned out, and surgeries take longer to schedule and more get canceled, humanoid surgical robots offer a solution. That’s the argument that UC San Diego robotics expert Michael Yip makes in a perspective piece in Science Robotics.

Today’s surgical robots are costly pieces of equipment designed for specialized tasks and can only be operated by highly trained physicians. However, this model doesn’t scale.

Despite the drastic improvements in artificial intelligence and autonomy for industrial and humanoid robots in the past year, these improvements haven’t translated to surgical robots.