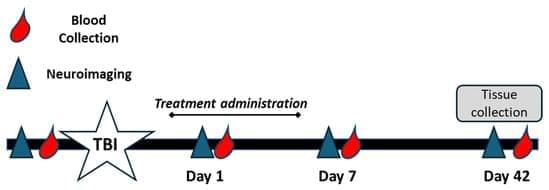

Background/Objectives: Traumatic brain injury (TBI) is a global leading cause of disability and death, with millions of new cases added each year. Oxidative stress significantly exacerbates primary TBI, leading to increased levels of intracerebral cell death, tissue loss, and long-term functional deficits in surviving patients. Catalase and superoxide dismutase (SOD) mitigate oxidative stress and play a critical role in dampening injury severity. This study examines the neuroprotective effects of the novel antioxidant alpha lipoic acid-based therapeutic, CMX-2043, on antioxidant enzymes in a preclinical TBI model via various drug administration routes. Methods: Piglets (n = 28) underwent cortical controlled impact to induce moderate–severe TBI and were assigned to placebo (n = 10), subcutaneous CMX-2043 (SQ, 10 mg/kg; n = 9), or intravenous CMX-2043 (IV, 9 mg/kg; n = 9) treatment groups. Treatments began 1 h after TBI induction and continued for 5 days. MRI was performed throughout the study period to evaluate brain recovery. Blood was collected at 1, 7, and 42 days post-TBI, and liver and brain tissues were collected at 42 days post-TBI to measure catalase and SOD activity. Results: CMX-2043 IV-treated piglets showed 46.3% higher hepatic catalase activity than placebo (p = 0.0038), while the SQ group did not show significant changes in hepatic catalase activity compared to placebo. In the brain, SQ-treated piglets had significantly higher catalase activity than both IV (p = 0.0163) and placebo (p = 0.0003) groups (45.8340 ± 3.0855, 36.4822 ± 1.5558, 31.6524 ± 1.3129 nmol/min/mg protein for SQ, IV, and placebo, respectively), while IV-treated piglets did not show significant changes compared to placebo. IV-treated piglets did exhibit 39.3% higher brain SOD activity than placebo (p = 0.0148), while the SQ group did not show a significant change. CMX-2043 treatment did not alter plasma antioxidant enzyme activity during the study period. Importantly, within CMX-2043 treated TBI groups, piglets with significantly decreased lesion volumes, midline shift, and combined swelling and atrophy had better brain recovery, determined by MRI on day 1, 7, and 42 days post-injury TBI, exhibited higher brain catalase activity at 42 days post-injury TBI regardless of administration route, suggesting a link between improved recovery and sustained local catalase activity. Conclusions: This study highlights the impact of administration route on tissue-specific antioxidant responses, with IV administration enhancing liver catalase and brain SOD activity, while SQ administration primarily elevated brain catalase activity. In addition, this study shows an association between increased brain catalase activity and decreased TBI brain lesioning, midline shift, and combined swelling and atrophy, thus emphasizing the role of antioxidant defenses in neuroprotection post-injury.