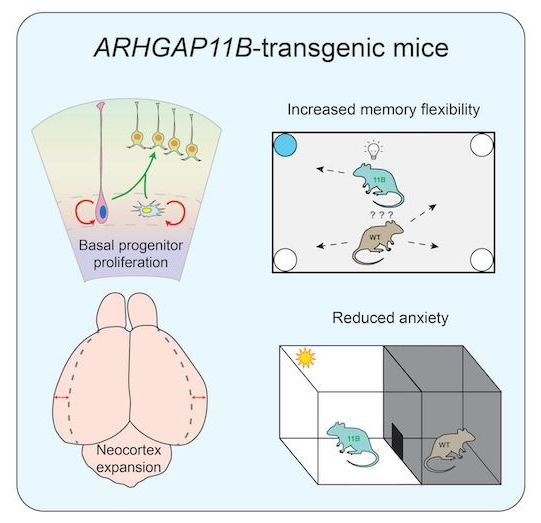

The idea is simple: decades of research have found certain genes that seem to increase the chance of Alzheimer’s and other dementias. The numbers range over hundreds. Figuring out how each connects or influences another—if at all—takes years of research in individual labs. What if scientists unite, tap into a shared resource, and collectively solve the case of why Alzheimer’s occurs in the first place?

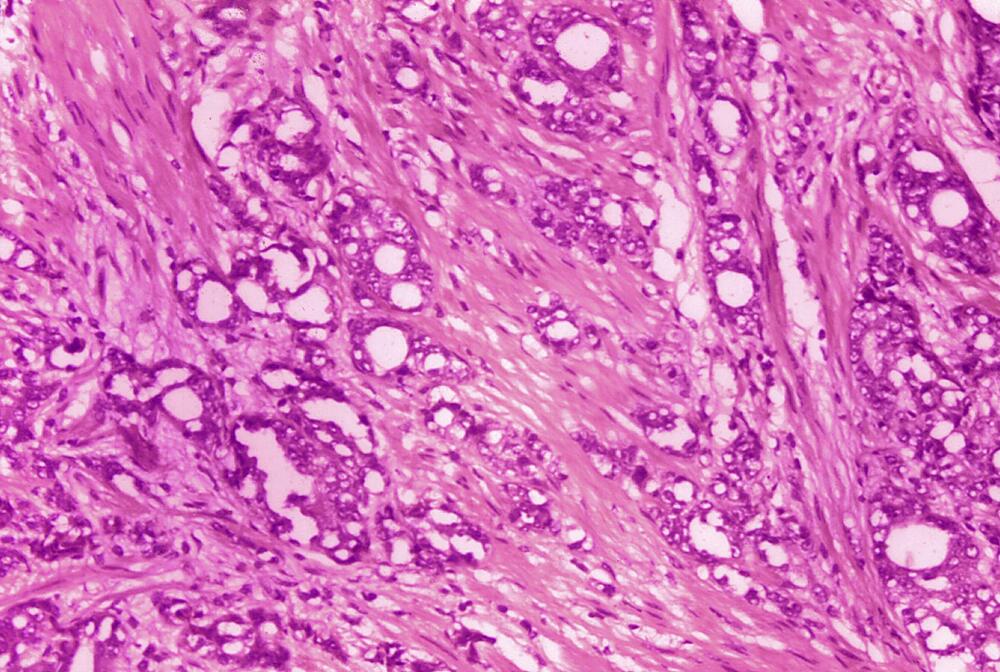

The initiative’s secret weapon is induced pluripotent stem cells, or iPSCs. Similar to most stem cells, they have the ability to transform into anything—a cellular genie, if you will. iPSCs are reborn from regular adult cells, such as skin cells. When transformed into a brain cell, however, they carry the original genes of their donor, meaning that they harbor the original person’s genetic legacy—for example, his or her chance of developing Alzheimer’s in the first place. What if we introduce Alzheimer’s-related genes into these reborn stem cells, and watch how they behave?

By studying these iPSCs, we might be able to follow clues that lead to the genetic causes of Alzheimer’s and other dementias—paving the road for gene therapies to nip them in the bud.