How is Cuba’s one dose vaccine working 🤔

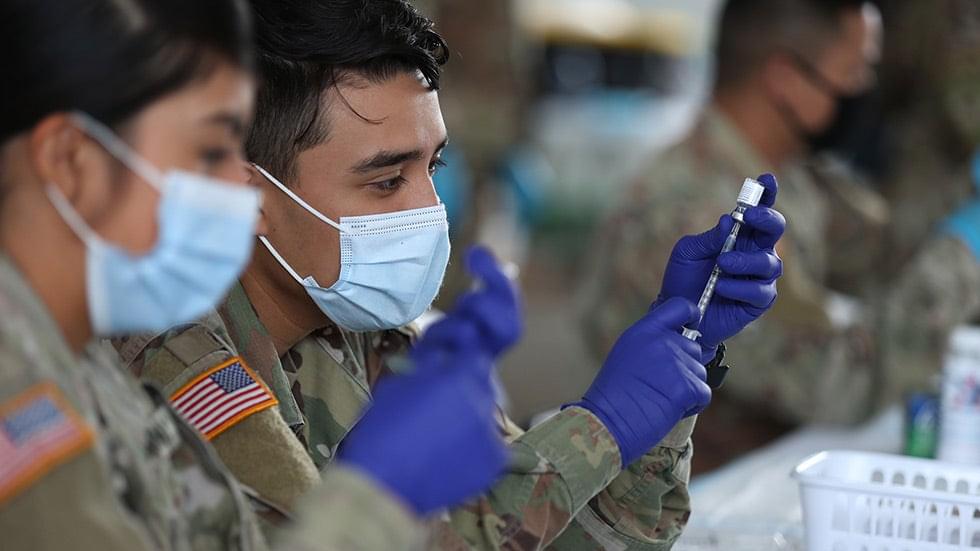

HAVANA, Dec 20 (Reuters) — Cuba has vaccinated more of its citizens against COVID-19 than most of the world’s largest and richest nations, a milestone that will make the poor, communist-run country a test case as the highly contagious Omicron variant begins to circle the globe.

The Caribbean island has vaccinated over 90% of its population with at least one dose, and 83% of the population is now fully inoculated, placing it second globally behind only the United Arab Emirates among countries of at least 1 million people, according to official statistics compiled by ‘Our World in Data.’

What is Cuba’s secret? While many of its neighbors in Latin America, as well as emerging economies globally, have competed for vaccines produced by wealthier nations, health officials say Cuba vaulted ahead by developing its own.