A growing body of research underscores that Alzheimer’s and cognitive decline are not inevitable parts of aging.

Researchers have provided new insights into how exercise helps lose weight. They discovered a mechanism by which the compound Lac-Phe, which is produced during exercise, reduces appetite in mice, leading to weight loss. The findings appeared in Nature Metabolism.

“Regular exercise is considered a powerful way to lose weight and to protect from obesity-associated diseases, such as diabetes or heart conditions,” said co-corresponding author Dr. Yang He, assistant professor of pediatrics—neurology at Baylor and investigator at the Duncan NRI. “Exercise helps lose weight by increasing the amount of energy the body uses; however, it is likely that other mechanisms are also involved.”

The researchers previously discovered that Lac-Phe is the most increased metabolite—a product of the body’s metabolism—in blood after intense exercise, not just in mice but also in humans and racehorses. The team’s previous work showed that giving Lac-Phe to obese mice reduced how much they ate and helped them lose weight without negative side effects. But until now, scientists didn’t fully understand how Lac-Phe works to suppress appetite.

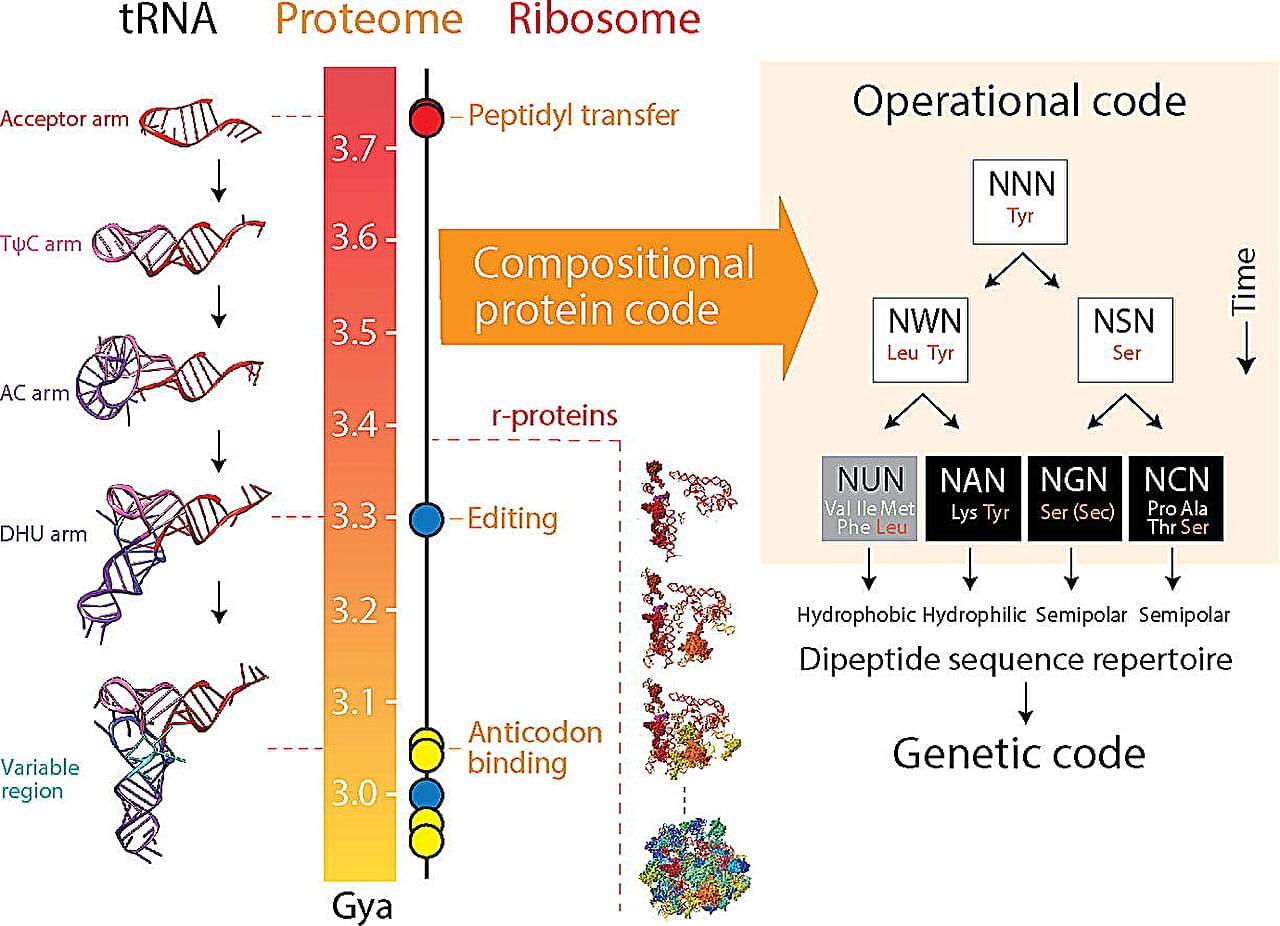

Genes are the building blocks of life, and the genetic code provides the instructions for the complex processes that make organisms function. But how and why did it come to be the way it is?

A recent study from the University of Illinois Urbana-Champaign sheds new light on the origin and evolution of the genetic code, providing valuable insights for genetic engineering and bioinformatics. The study is published in the Journal of Molecular Biology.

“We find the origin of the genetic code mysteriously linked to the dipeptide composition of a proteome, the collective of proteins in an organism,” said corresponding author Gustavo Caetano-Anollés, professor in the Department of Crop Sciences, the Carl R. Woese Institute for Genomic Biology, and Biomedical and Translation Sciences of Carle Illinois College of Medicine at U. of I.

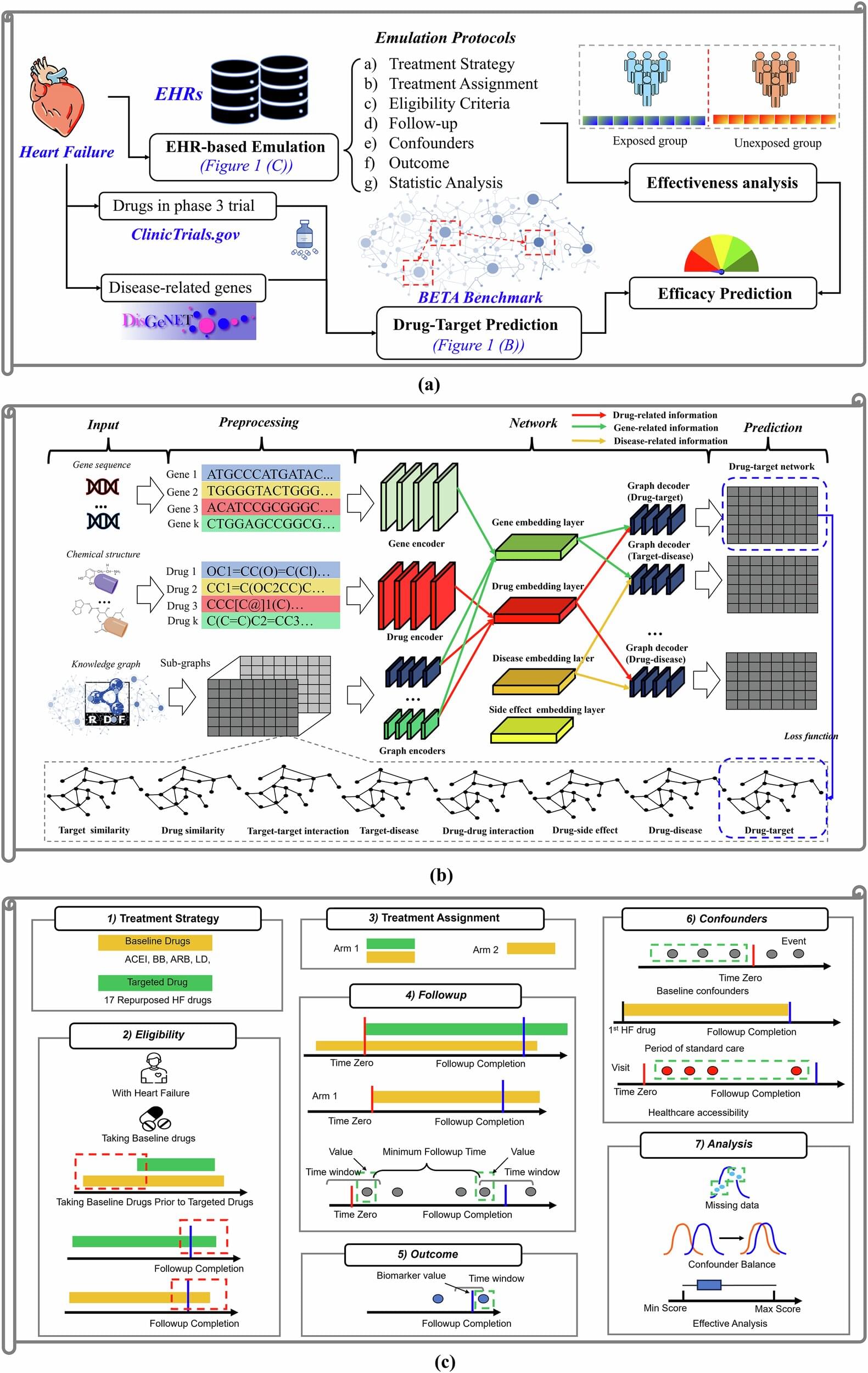

Mayo Clinic researchers have developed a new way to predict whether existing drugs could be repurposed to treat heart failure, one of the world’s most pressing health challenges. By combining advanced computer modeling with real-world patient data, the team has created “virtual clinical trials” that may facilitate the discovery of effective therapies while reducing the time, cost, and risk of failed studies.

“We’ve shown that with our framework, we can predict the clinical effect of a drug without a randomized controlled trial. We can say with high confidence if a drug is likely to succeed or not,” says Nansu Zong, Ph.D., a biomedical informatician at Mayo Clinic and lead author of the study, which was published in npj Digital Medicine.

MIT researchers developed a fully autonomous platform that can identify, mix, and characterize novel polymer blends until it finds the optimal blend. This system could streamline the design of new composite materials for sustainable biocatalysis, better batteries, cheaper solar panels, and safer drug-delivery materials.

Stanford Medicine researchers have developed an artificial intelligence tool to help scientists better plan gene-editing experiments. The technology, CRISPR-GPT, acts as a gene-editing “copilot” supported by AI to help researchers—even those unfamiliar with gene editing—generate designs, analyze data and troubleshoot design flaws.

The model builds on a tool called CRISPR, a powerful gene-editing technology used to edit genomes and develop therapies for genetic diseases. But training on the tool to design an experiment is complicated and time-consuming—even for seasoned scientists. CRISPR-GPT speeds that process along, automating much of the experimental design and refinement. The goal, said Le Cong, Ph.D., assistant professor of pathology and genetics, who led the technology’s development, is to help scientists produce lifesaving drugs faster.

The paper is published in the journal Nature Biomedical Engineering.

Mortality after emergency abdominal surgery is more than three times higher in the least developed countries compared to the most developed. Yet among those who undergo surgery, injuries tend to be less severe—raising concerns that those most critically injured are not even reaching the operating theater.

A study published in The Lancet Global Health has revealed stark global inequalities in survival after emergency abdominal surgery for traumatic injuries. The research found that patients in the world’s least developed countries face a substantially higher risk of dying within 30 days of surgery than those in the most developed nations, as ranked by the United Nations Human Development Index (HDI).

Although overall mortality rates appeared similar across settings at 11%, risk-adjusted analysis showed that patients in the lowest-HDI countries faced more than three times the risk of death compared with those in the highest-HDI group, while the risk in middle-HDI countries was nearly double.