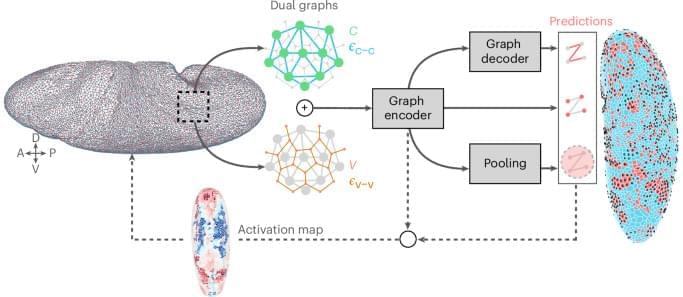

MultiCell is a deep learning method to capture complex cell dynamics during multicellular development.

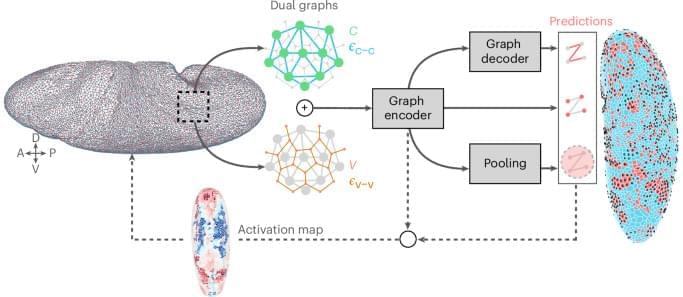

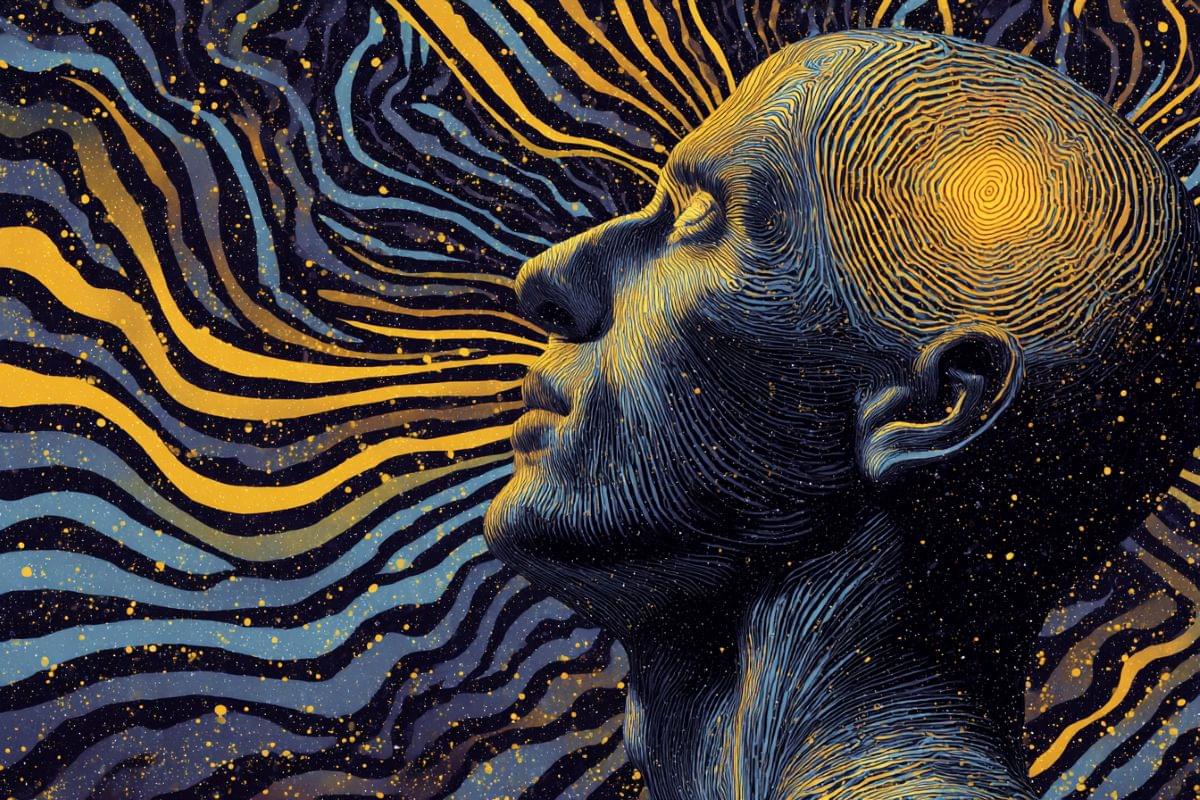

The rapid advances in the capabilities of Large Language Models (LLMs) have galvanised public and scientific debates over whether artificial systems might one day be conscious. Prevailing optimism is often grounded in computational functionalism: the assumption that consciousness is determined solely by the right pattern of information processing, independent of the physical substrate. Opposing this, biological naturalism insists that conscious experience is fundamentally dependent on the concrete physical processes of living systems. Despite the centrality of these positions to the artificial consciousness debate, there is currently no coherent framework that explains how biological computation differs from digital computation, and why this difference might matter for consciousness.

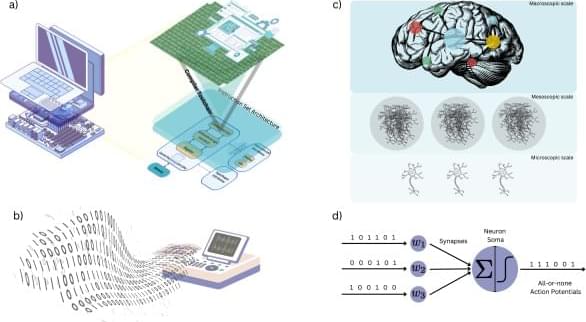

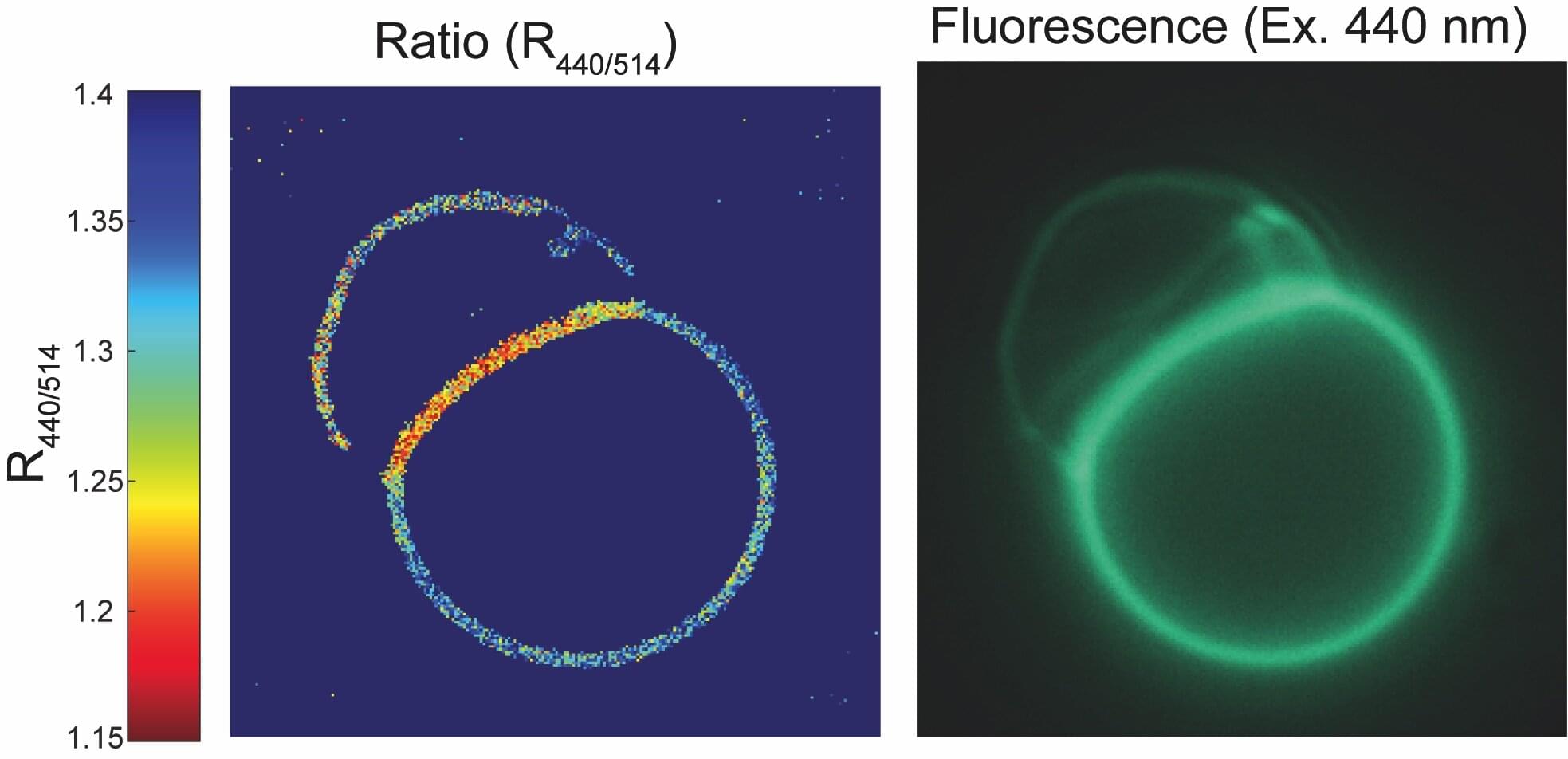

Cells may generate their own electrical signals through microscopic membrane motions. Researchers show that active molecular processes can create voltage spikes similar to those used by neurons. These signals could help drive ion transport and explain key biological functions. The work may also guide the design of intelligent, bio-inspired materials.

The breakthrough wasn’t speed or scale, but a neural architecture that finally respected protein geometry.

AlphaFold didn’t accelerate biology by running faster experiments. It changed the engineering assumptions behind protein structure prediction.

Many biological processes are regulated by electricity—from nerve impulses to heartbeats to the movement of molecules in and out of cells.

A study by Scripps Research scientists reveals a previously unknown potential regulator of this bioelectricity: droplet-like structures called condensates. Condensates are better known for their role in compartmentalizing the cell, but this study shows they can also act as tiny biological batteries that charge the cell membrane from within.

The team showed that when electrically charged condensates collide with cell membranes, they change the cell membrane’s voltage—which influences the amount of electrical charge flowing across the membrane—at the point of contact.

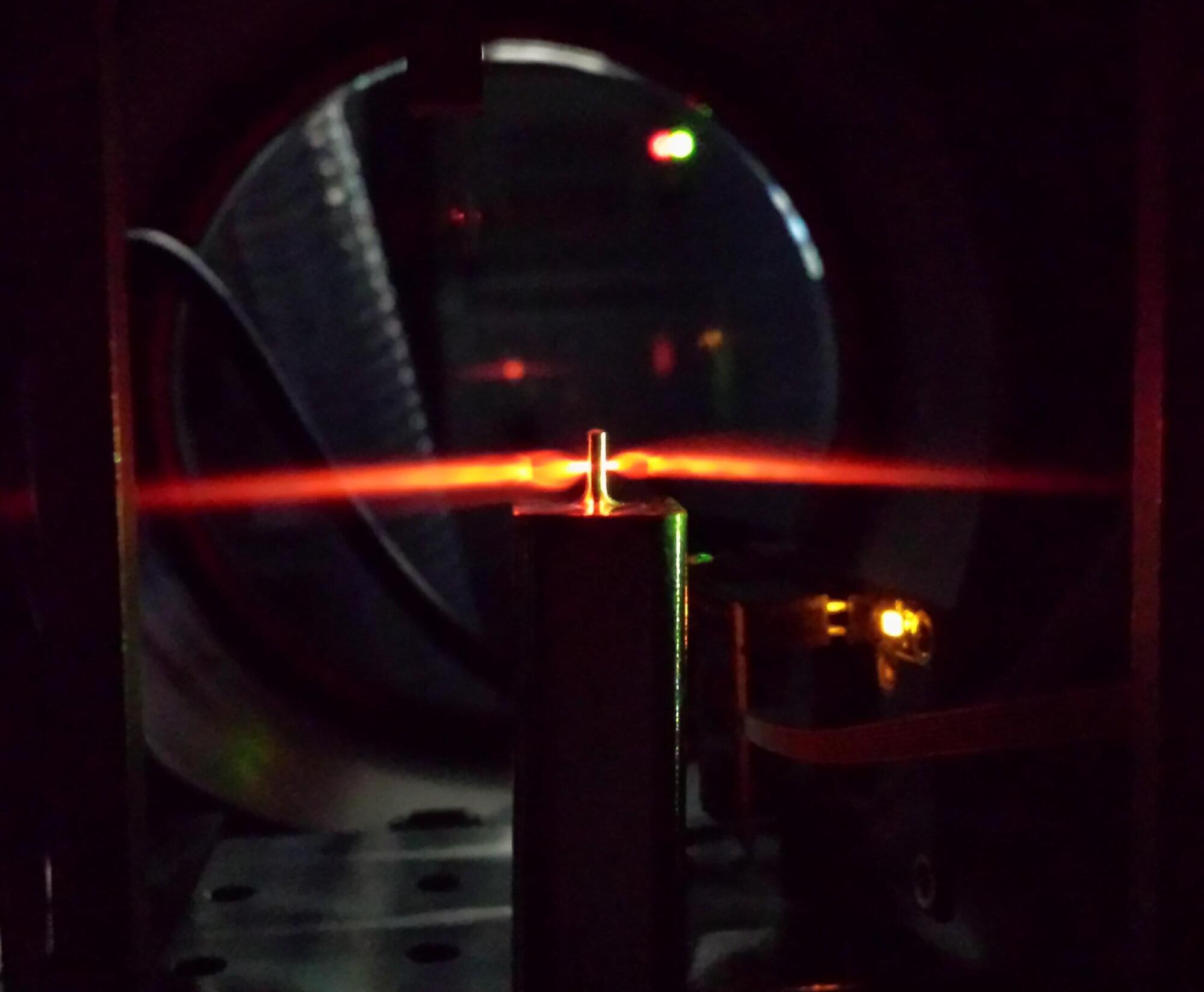

Electrons determine everything: how chemical reactions unfold, how materials conduct electricity, how biological molecules transfer energy, and how quantum technologies operate. But electron dynamics happens on attosecond timescales—far too fast for conventional measurement tools.

Researchers have now generated a 19.2-attosecond soft X-ray pulse, which effectively creates a camera capable of capturing these elusive dynamics in real time with unprecedented detail, enabling the observation of processes never observed before. Dr. Fernando Ardana-Lamas, Dr. Seth L. Cousin, Juliette Lignieres, and ICREA Prof. Jens Biegert, at ICFO, has published this new record in Ultrafast Science. At just 19.2 attoseconds long, it is the shortest and brightest soft X-ray pulse ever produced, giving rise to the fastest “camera” in existence.

Flashes of light in the soft X-ray spectral range provide fingerprinting identification, allowing scientists to track how electrons reorganize around specific atoms during reactions or phase transitions. Generating an isolated pulse this short, required innovations in high-harmonic generation, advanced laser engineering, and attosecond metrology. Together, these developments allow researchers to observe electron dynamics, which define material properties, at their natural timescales.

Jim Al-Khalili explores emerging technologies powering the future of quantum, and looks at how we got here.

This Discourse was recorded at the Ri on 7 November 2025, in partnership with the Institute of Physics.

Watch the Q&A session for this talk here (exclusively for our Science Supporter members):

Join this channel as a member to get access to perks:

/ @theroyalinstitution.

Physicist and renowned broadcaster Jim Al-Khalili takes a look back at a century of quantum mechanics, the strangest yet most successful theory in all of science, and how it has shaped our world. He also looks forward to the exciting new world of Quantum 2.0 and how a deeper understanding of such counterintuitive concepts as quantum superposition and quantum entanglement is leading to the development of entirely new technologies, from quantum computers and quantum sensors to quantum cryptography and the quantum internet.

The United Nations has proclaimed 2025 as the International Year of Quantum Science and Technology, to celebrate the centenary of quantum mechanics and the revolutionary work of the likes of Werner Heisenberg and Erwin Schrödinger. Together with the Institute of Physics, join us to celebrate the culmination of the International Year of Quantum at the penultimate Discourse of our Discover200 year.

-

A new study from the University of Miami Rosenstiel School of Marine, Atmospheric, and Earth Science and the Marine Megafauna Foundation finds that young Caribbean manta rays (Mobula yarae) often swim with groups of other fish, creating small, moving ecosystems that support a variety of marine species.

The paper is published in the journal Marine Biology.

South Florida —particularly Palm Beach County—serves as a nursery for juvenile manta rays. For nearly a decade, the Marine Megafauna Foundation has been studying these rays and documenting the challenges they face from human activities near the coast, such as boat strikes and entanglement in fishing gear, which can pose significant threats to juvenile mantas.

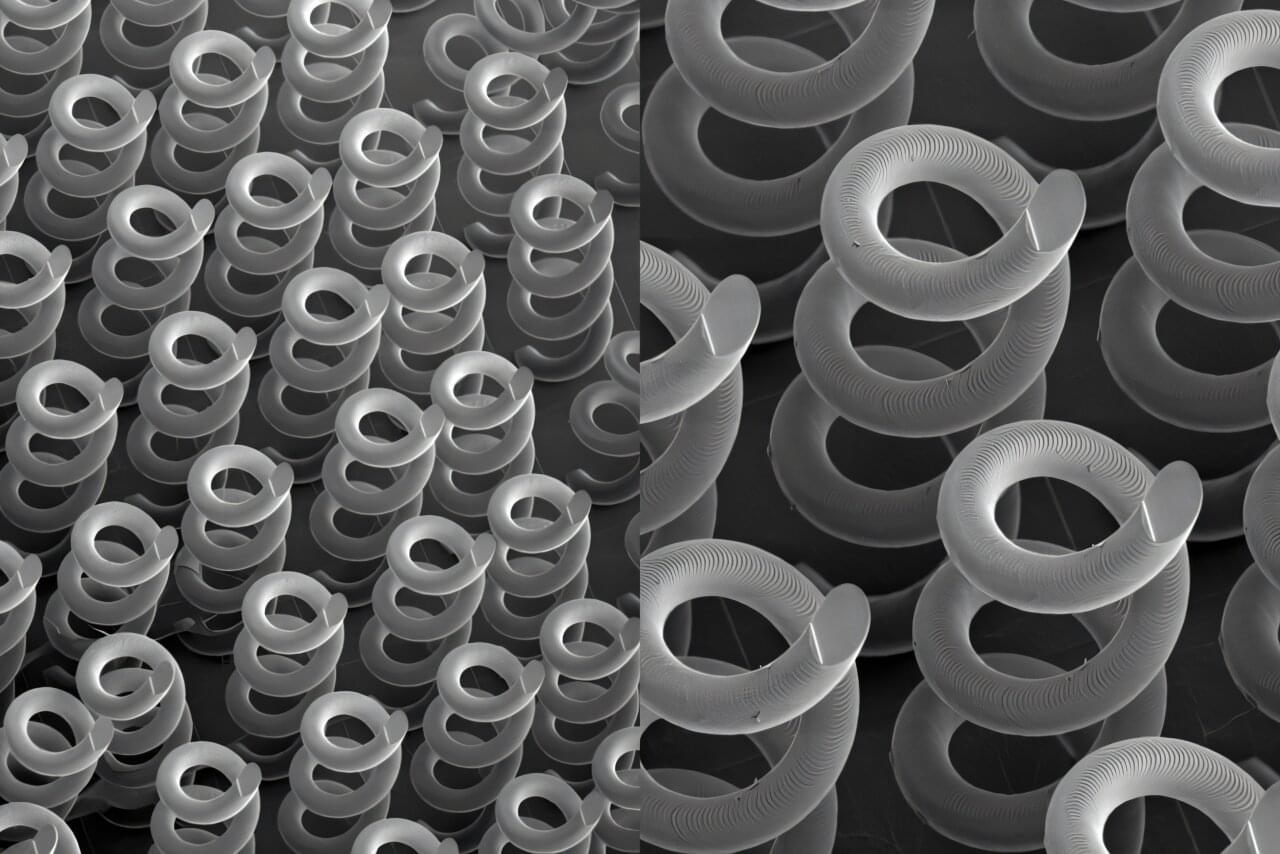

Researchers at Lawrence Livermore National Laboratory (LLNL) have optimized and 3D-printed helix structures as optical materials for terahertz (THz) frequencies, a potential way to address a technology gap for next-generation telecommunications, non-destructive evaluation, chemical/biological sensing and more.

The printed microscale helices reliably create circularly polarized beams in the THz range and, when arranged in patterned arrays, can function as a new type of Quick Response (QR) for advanced encryption/decryption. Their results, published in Advanced Science, represent the first full parametric analysis of helical structures for THz frequencies and show the potential of 3D printing for fabricating THz devices.