Circa 2011 o,.o Foglet bodies around the corner sooner than we think 🤔

Could living things that evolved from metals be clunking about somewhere in the universe? Perhaps. In a lab in Glasgow, UK, one man is intent on proving that metal-based life is possible.

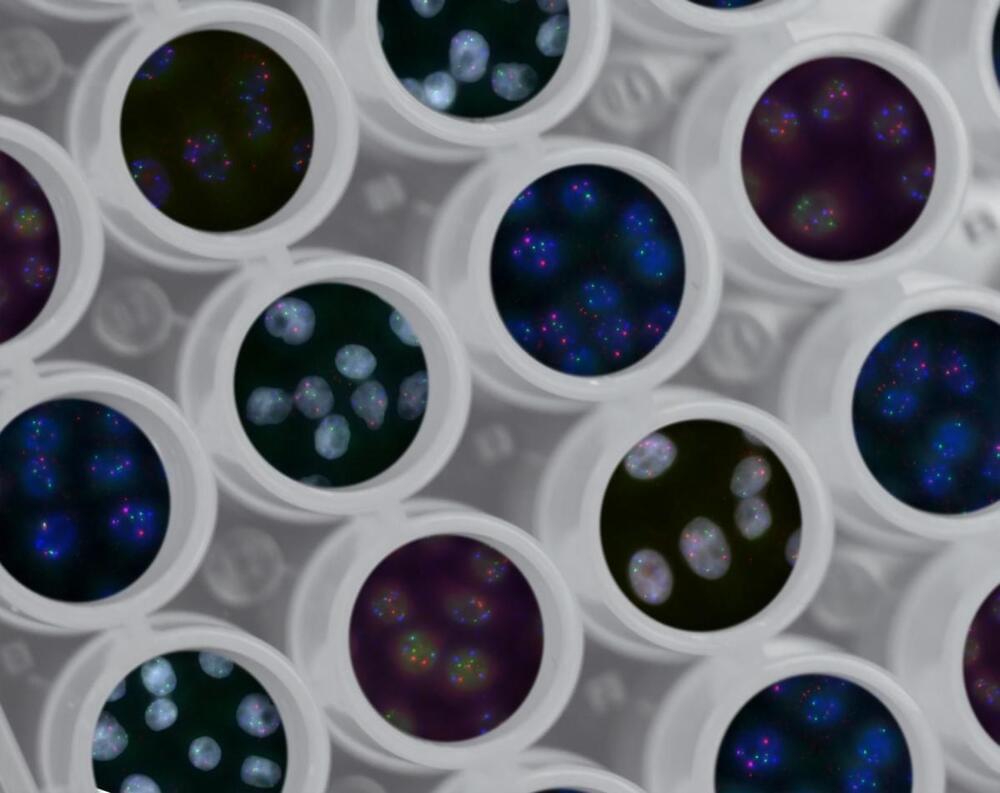

He has managed to build cell-like bubbles from giant metal-containing molecules and has given them some life-like properties. He now hopes to induce them to evolve into fully inorganic self-replicating entities.

“I am 100 per cent positive that we can get evolution to work outside organic biology,” says Lee Cronin (see photo, right) at the University of Glasgow. His building blocks are large “polyoxometalates” made of a range of metal atoms – most recently tungsten – linked to oxygen and phosphorus. By simply mixing them in solution, he can get them to self-assemble into cell-like spheres.