DNA writing is an aspect of our industry that I’ve been closely watching for several years because it is a critical component of so many groundbreaking capabilities, from cell and gene therapies to DNA data storage. At the SynBioBeta Conference in 2018, the co-founder of a new startup that was barely more than an idea gave a lightning talk on enzymatic DNA synthesis — and I was so struck by the technology the company was aiming to develop that I listed them as one of four synthetic biology startups to watch in 2019. I watched them, and I wasn’t disappointed.

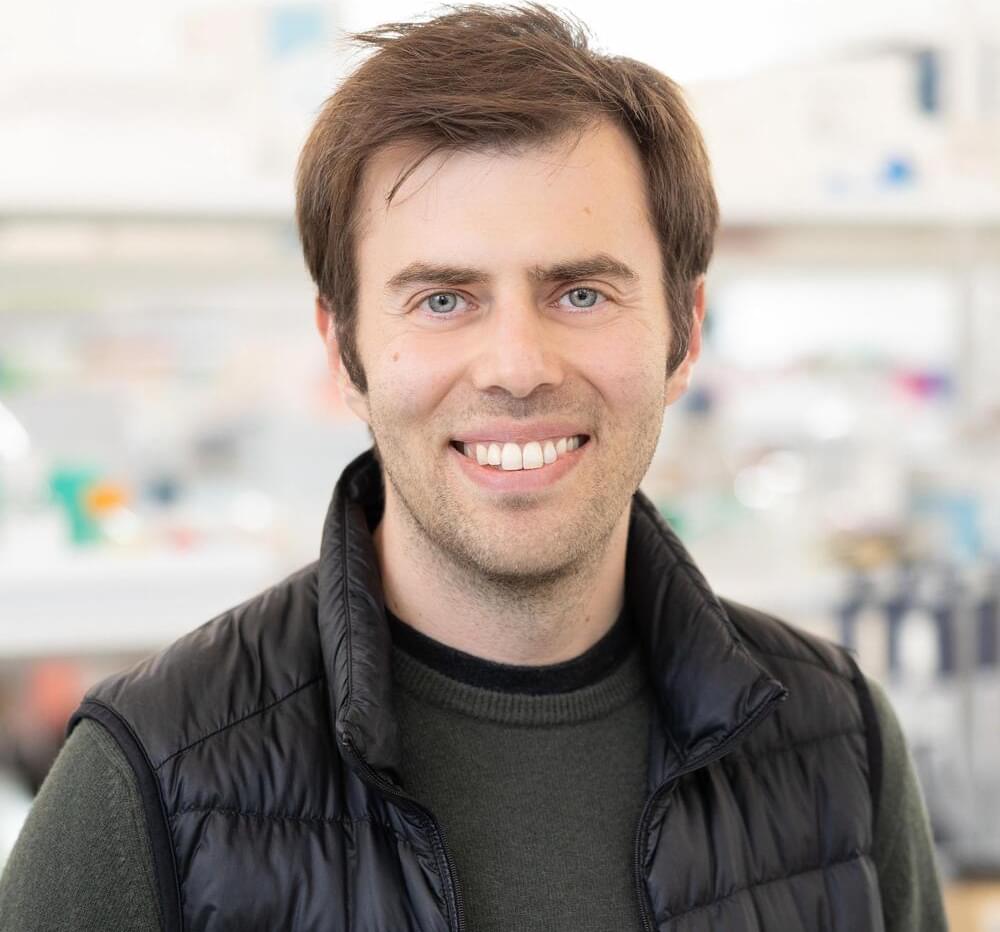

Ansa Biotechnologies, Inc. — the Emeryville, California-based DNA synthesis startup using enzymes instead of chemicals to write DNA — announced in March the successful de novo synthesis of a 1005-mer, the world’s longest synthetic oligonucleotide, encoding a key part of the AAV vector used for developing gene therapies. And that’s just the beginning. Co-founder Dan Lin-Arlow will be giving another lightning talk at this year’s SynBioBeta Conference in just a few weeks. I caught up with him in the lead up and was truly impressed by what Ansa Biotechnologies has accomplished in just 5 years.

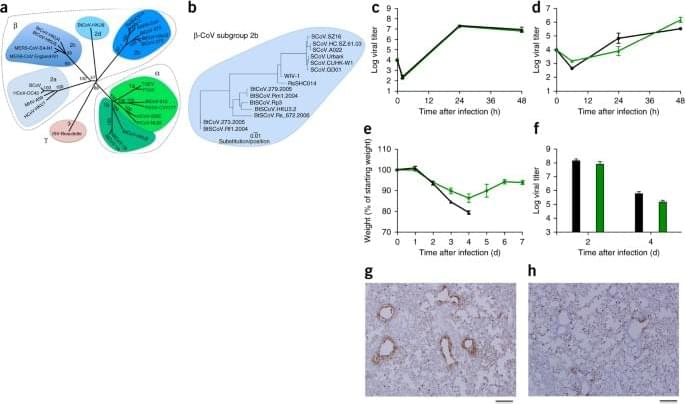

Synthetic DNA is a key enabling technology for engineering biology. For nearly 40 years, synthetic DNA has been produced using phosphoramidite chemistry, which facilitates the sequential addition of new bases to a DNA chain in a simple cyclic reaction. While this process is incredibly efficient and has supported countless innovative breakthroughs (a visit to Twist Bioscience’s website will quickly educate you on exciting advances in drug discovery, infectious disease research, cancer therapeutics, and even agriculture enabled by synthetic DNA) it suffers from two main drawbacks: its reliance on harsh chemicals and its inability to produce long (read: complex) DNA fragments.