Researchers designed nanoparticles that can deliver mRNA gene editing solutions directly to the lungs to address rare genetic diseases.

It was an honor to speak at MIT’s Broad Institute about some of my past and present synthetic biology research on redesigning bacteria and viruses to act as delivery systems for biomedicine! Video recording is now available! Here is a link which should take you to 1:40:18 when my talk starts:[ ]. My talk was part of the inaugural MIT Biosummit (https://mitbiosummit.com/), a forward-looking conference which this year focused on tackling challenges at the interface of climate change and health sciences. #futureofmedicine #future #biotech #mit Thank you Ryan Robinson for helping to organize this conference and for giving your own excellent talk!

Recording of the MIT Club of Boston 2023 BioSummit: Human Health 2050 held at the Broad Institute on April 27, 2023. Note: Although the video is almost 6 hours long, you can rapidly navigate and skip to a particular speaker or session by scrubbing along the video timeline (in Chrome or Edge) or using the time markers listed below in blue (in all browsers). You can also use chapter browsing in the YouTube app on platforms where it is available.

0:00:00 Introductory remarks: Ryan Robinson, Whitney Espich.

0:08:44 Morning keynote: Bradley Willcox.

0:57:14 Infectious disease panel introduction, Lindsey Baden.

1:02:21 Kieren Marr.

1:38:27 Speaker transition with Lindsey Baden.

1:39:36 Logan Collins.

1:56:36 Ryan Robinson.

2:13:13 Infectious disease panel Q&A

2:24:00 Longevity panel introduction, Eduardo Cornejo.

2:27:14 Joseph Coughlin.

2:46:47 Vladim Gladyshev.

3:02:28 Cavin Ward-Caviness.

3:18:55 Longevity panel Q&A

3:37:44 Food supply panel introduction, Viji Thomas.

3:48:32 Gary Cohen.

4:05:16 Greg Sixt.

4:21:50 Anirban Kundu.

4:37:32 Food supply panel Q&A

5:15:03 Sebastian Eastham.

5:42:13 Closing remarks, preview of next year’s BioSummit Stephanie Licata.

Geoffrey Hinton, a VP and engineering fellow at Google and a pioneer of deep learning who developed some of the most important techniques at the heart of modern AI, is leaving the company after 10 years, the New York Times reported today.

According to the Times, Hinton says he has new fears about the technology he helped usher in and wants to speak openly about them, and that a part of him now regrets his life’s work.

While the world has been captivated by recent advances in artificial intelligence, researchers at Johns Hopkins University have identified a new form of intelligence: organoid intelligence. A future where computers are powered by lab-grown brain cells may be closer than we could ever have imagined.

What is an organoid? Organoids are three-dimensional tissue cultures commonly derived from human pluripotent stem cells. What looks like a clump of cells can be engineered to function like a human organ, mirroring its key structural and biological characteristics. Under the right laboratory conditions, genetic instructions from donated stem cells allow organoids to self-organize and grow into any type of organ tissue, including the human brain.

Although this may sound like science-fiction, brain organoids have been used to model and study neurodegenerative diseases for nearly a decade. Emerging studies now reveal that these lab grown brain cells may be capable of learning. In fact, a research team from Melbourne recently reported that they trained 800,000 brain cells to perform the computer game, Pong (see video). As this field of research continues to grow, researchers speculate that this so-called “intelligence in a dish” may be able to outcompete artificial intelligence.

A stream of air bubbles can be most effective at cleaning produce or industrial equipment if it strikes at the correct angle.

Researchers believe that washing vegetables and food-processing equipment with flowing liquids filled with air bubbles could be effective, but little is known about how to optimize the process. Now engineers, using experiments and simulations, have shown that bubbles exert an optimal cleaning effect if they strike a surface at an angle of about 22.5° [1]. The researchers hope that this insight will help improve methods for the gentle cleaning of fruits and vegetables, potentially leading to a commercial food-cleaning device that they call a “fruit Jacuzzi.”

As bioengineer Sunghwan “Sunny” Jung of Cornell University points out, bubbles injected into fluid have long been used to clean biofilm-encrusted surfaces in settings such as wastewater treatment facilities. Experts generally believe that the technique works because bubbles flowing over a surface exert a shear force, parallel to the surface, which tends to remove attached contaminants. “It’s similar to how you move your hand along the surface of your skin when you’re cleaning your body, applying a shearing force at the surface,” says Jung. Even so, he says, little is known about the basic science behind the effect and in particular about how the motions of bubbles within the liquid might optimize the cleaning.

The potential of satellite-based synthetic biology and genetic engineering to revolutionize healthcare is becoming increasingly clear. Recent advances in the field have opened up a world of possibilities for medical professionals and researchers, allowing them to diagnose and treat diseases more effectively and efficiently than ever before.

Satellite-based synthetic biology and genetic engineering have already been used to develop treatments for a variety of conditions, including cancer, heart disease, and neurological disorders. By using satellite-based techniques, researchers can quickly and accurately identify genetic mutations and other abnormalities in a patient’s DNA. This allows them to develop personalized treatments that are tailored to the individual’s specific needs.

The use of satellite-based synthetic biology and genetic engineering also has the potential to reduce healthcare costs. By identifying genetic mutations and other abnormalities at an early stage, doctors can avoid costly and unnecessary treatments. This could lead to significant savings for both patients and healthcare providers.

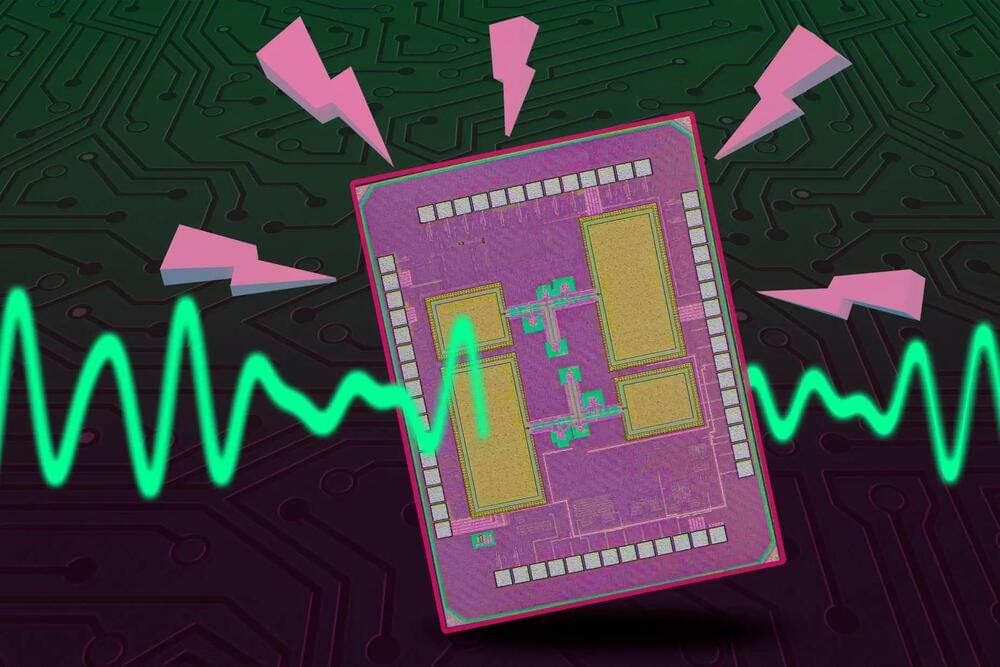

Researchers demonstrate a low-power “wake-up” receiver one-tenth the size of other devices.

MIT

MIT is an acronym for the Massachusetts Institute of Technology. It is a prestigious private research university in Cambridge, Massachusetts that was founded in 1861. It is organized into five Schools: architecture and planning; engineering; humanities, arts, and social sciences; management; and science. MIT’s impact includes many scientific breakthroughs and technological advances. Their stated goal is to make a better world through education, research, and innovation.

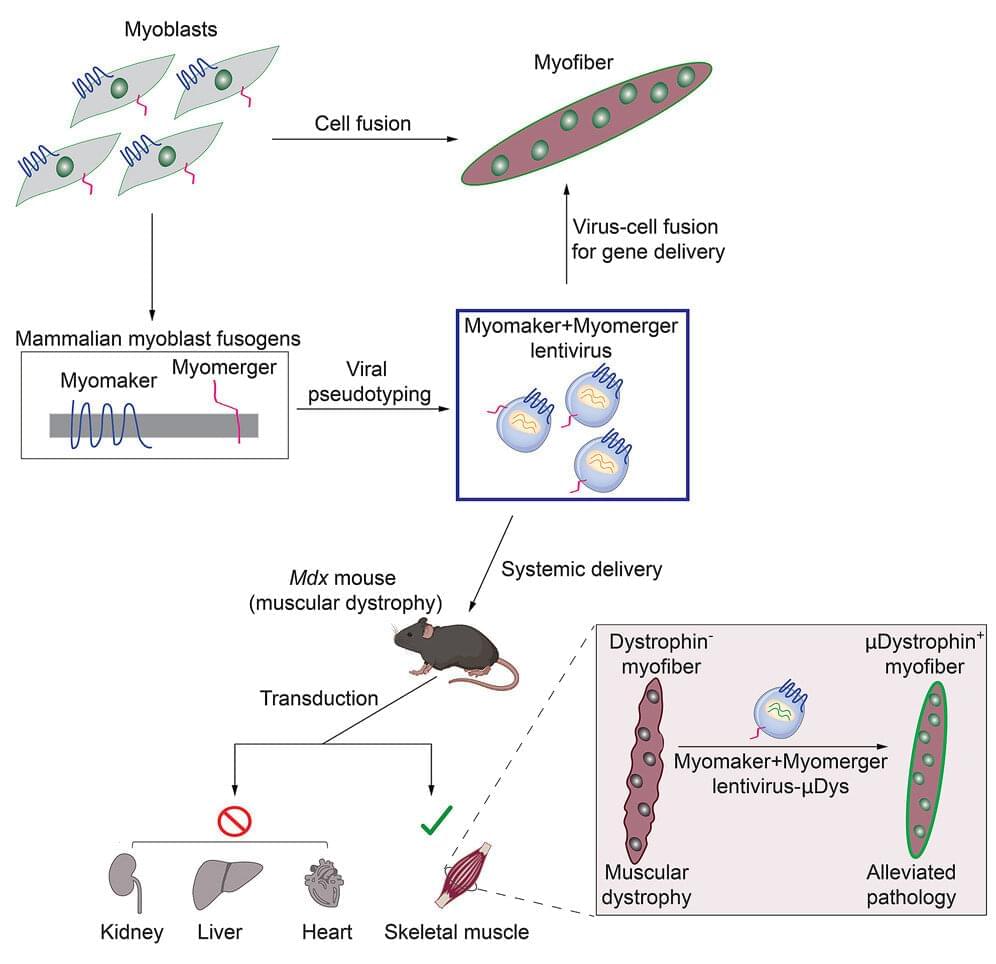

Doug Millay, Ph.D., a scientist with the Division of Molecular Cardiovascular Biology at Cincinnati Children’s has dedicated his career to revealing the most fundamental mechanisms of skeletal muscle development. He has been a leader in characterizing how two “fusogens” called Myomaker and Myomerger mediate the entry of stem cells into mature muscle cells to build the tissue that humans depend upon for movement, breathing, and survival.

Now, some of the basic discoveries made by Millay and colleagues are translating into a potential treatment for people living with Duchenne muscular dystrophy (DMD). Their latest research, published April 12, 2023, in the journal Cell, reveals that in mice, modified viruses, engineered with Myomaker and Myomerger, result in specific fusion with muscle cells. These viruses can therefore be used as a vector to deliver a vital gene needed for muscle function that is mutated in people with DMD.

A key unknown prior to this work was whether proteins like Myomaker and Myomerger, which mainly function on cells, could even work on viruses. First author Sajedah Hindi, Ph.D., also with the Division of Molecular Cardiovascular Biology at Cincinnati Children’s and a leading member of the research team, took on the challenge to test this idea.

A causal relationship exists among the aging process, organ decay and dis-function, and the occurrence of various diseases including cancer. A genetically engineered mouse model, termed EklfK74R/K74R or Eklf (K74R), carrying mutation on the well-conserved sumoylation site of the hematopoietic transcription factor KLF1/ EKLF has been generated that possesses extended lifespan and healthy characteristics including cancer resistance. We show that the high anti-cancer capability of the Eklf (K74R) mice are gender-, age-and genetic background-independent. Significantly, the anti-cancer capability and extended lifespan characteristics of Eklf (K74R) mice could be transferred to wild-type mice via transplantation of their bone marrow mononuclear cells. Targeted/global gene expression profiling analysis has identified changes of the expression of specific proteins and cellular pathways in the leukocytes of the Eklf (K74R) that are in the directions of anti-cancer and/or anti-aging. This study demonstrates the feasibility of developing a novel hematopoietic/ blood system for long-term anti-cancer and, potentially, for anti-aging.

The authors have declared no competing interest.

In parallel to recent developments in machine learning like GPT-4, a group of scientists has recently proposed the use of neural tissue itself, carefully grown to recreate the structures of the animal brain, as a computational substrate. After all, if AI is inspired by neurological systems, what better medium to do computing than an actual neurological system? Gathering developments from the fields of computer science, electrical engineering, neurobiology, electrophysiology, and pharmacology, the authors propose a new research initiative they call “organoid intelligence.”

OI is a collective effort to promote the use of brain organoids —tiny spherical masses of brain tissue grown from stem cells—for computation, drug research and as a model to study at a small scale how a complete brain may function. In other words, organoids provide an opportunity to better understand the brain, and OI aims to use that knowledge to develop neurobiological computational systems that learn from less data and with less energy than silicon hardware.

The development of organoids has been made possible by two bioengineering breakthroughs: induced pluripotent stem cells and 3D cell culturing techniques.