New ultralight hexagonal boron nitride material could be used in extreme-temperature applications such as spacecraft.

Researchers are using 3D printing to develop electrodes with the highest electric charge store per unit of surface area ever reported for a supercapacitor.

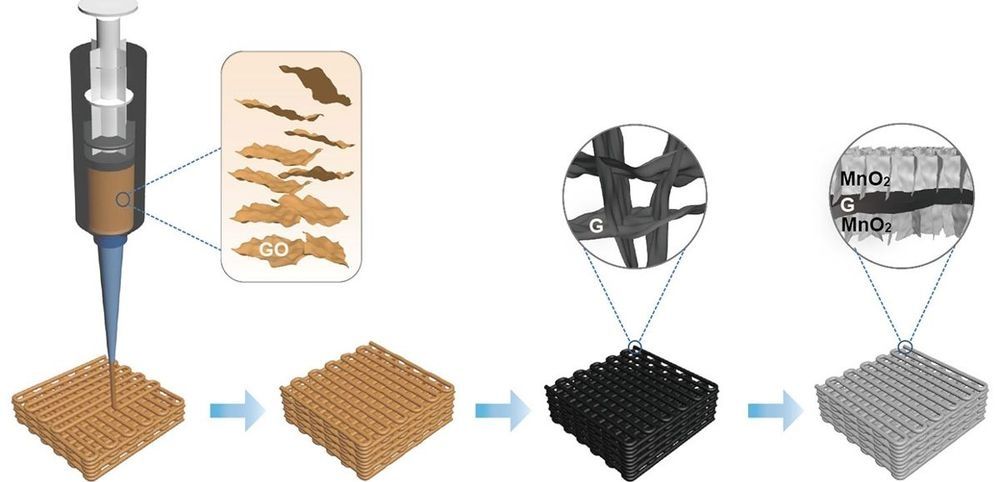

A research collaboration from the University of California Santa Cruz and the U.S. Department of Energy’s Lawrence Livermore National Laboratory have 3D printed a graphene aerogel that enabled them to develop a porous three-dimensional scaffold loaded with manganese oxide that yields better supercapacitor electrodes. The recently published their findings in Joule. Yat Li, a professor of chemistry and biochemistry at UC Santa Cruz, explained the breakthrough in an interview with R&D Magazine.

“So what we’re trying to address in this paper is really the loading of the materials and the amount of energy we can store,” Li said. “What we are trying to do is use a printing method to print where we can control the thickness and volume.

After what has seemed a bit of a lapse in the timeline of their development, graphene-enabled supercapacitors may be poised to make a significant advance. Researchers at the University of California, Santa Cruz, and Lawrence Livermore Laboratory (LLNL) have developed an electrode for supercapacitors made from a graphene-based aerogel. The new supercapacitor component has the highest areal capacitance (electric charge stored per unit of surface area) ever reported for a supercapacitor.

The 3D-printing technique they leveraged to make the graphene electrode may have finally addressed the trade-offs between the gravimetric (weight), areal (surface area), and volumetric (total volume) capacitance of supercapacitor electrodes that were previously thought to be unavoidable.

In previous uses of pure graphene aerogel electrodes with high surface area, volumetric capacitance always suffered. This issue has typically been exacerbated with 3D-printed graphene aerogel electrodes; volumetric capacitance was reduced even further because of the periodic large pores between the printed filaments.

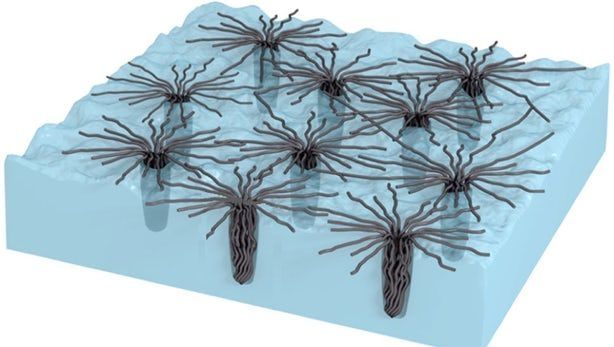

Lighter than air! Stronger than steel! More flexible than rubber! No, it’s not an upcoming superhero flick: It’s the latest marvelous formulation of carbon nanotubes–at least as reported by the creators of the new super-material. Researchers working on artificial muscles say they’ve created nanotech ribbons that make our human muscles look puny by comparison. The ribbons, which are made of long, entangled 11-nanometer-thick nanotubes, can stretch to more than three times their normal width but are stiffer and stronger than steel… They can expand and contract thousands of times and withstand temperatures ranging from −190 to over 1,600 °C. What’s more, they are almost as light as air, and are transparent, conductive, and flexible [Technology Review].

The material is made from bundles of vertically aligned nanotubes that respond directly to electricity. Lengthwise, the muscle can expand and contract with tremendous speed; from side-to-side, it’s super-stiff. Its possibilities may only be limited by the imaginations of engineers. [The material’s composition] “is akin to having diamond-like behavior in one direction, and rubber-like behavior in the others” [Wired], says material scientist John Madden, who wasn’t involved in the research.

When voltage is applied to the material, the nanotubes become charged and push each other away, causing the material to expand at a rate of 37,000 percent per second, tripling its width. That’s 10 times as far and 1000 times as fast as natural muscle can move, and the material does so while generating 30 times as much force as a natural muscle [IEEE Spectrum]. The researchers put together a video to illustrate the concept, and will publish their work in Science tomorrow.

Beam Me Down

Needless to say, the biggest problem for a floating power plant is figuring out how to get the energy back down to Earth.

The scientists behind the project are still sorting that part out. But right now, the plan is to have solar arrays in space capture light from the sun and then beam electricity down to a facility on Earth in the form of a microwave or a laser, according to The Sydney Morning Herald.