Scientists in Europe may have discovered a direct link between the human brain and the quantum nature of the universe itself.

The United States Air Force unveiled the B-21 Raider, a high-tech stealth bomber that can carry nuclear and conventional weapons and is designed to be able to fly without a crew on board. The fleet is estimated to cost $203 billion to develop, buy and operate over 30 years, according to Bloomberg, with the US planning to acquire at least 100 of the aircraft.

Much of the features of the warplane are shrouded in mystery, with reports suggesting that it has the potential for an uncrewed flight. A US Air Force spokeswoman said the aircraft was “provisioned for the possibility, but there has been no decision to fly without a crew”.

The first flight by a B-21 is expected to take place next year.

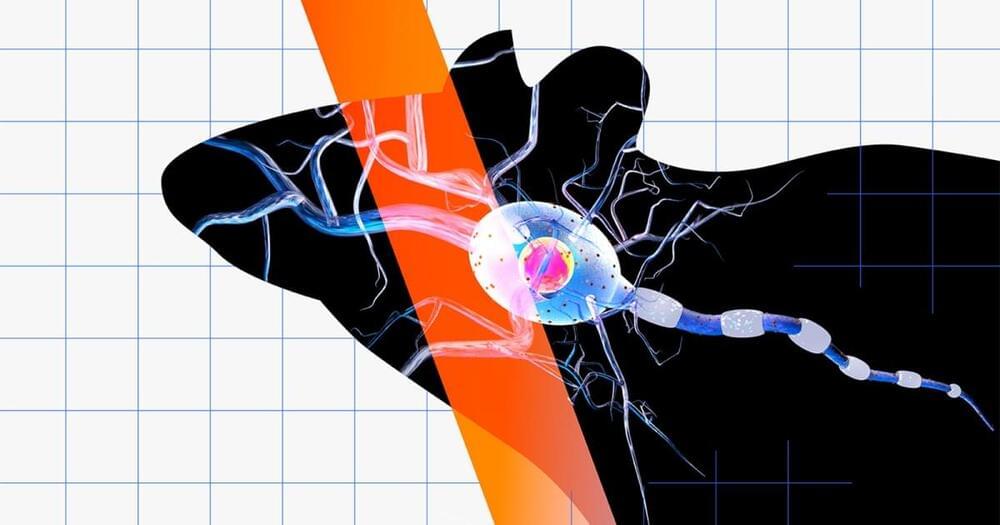

Researchers at Stanford and Singapore’s Nanyang Technological University (NTU) have developed a technique for controlling neurons from a distance, without invasive implants.

By injecting a molecule called TRPV1 — which helps us sense the heat in capsaicin chili peppers — into the brains of mice, they could control specific brain cells from up to one meter (about three feet) using infrared light beams.

The ability to impact neurons, without invasive surgical methods or tethers sticking out of skulls, could help researchers study the brain during more normal behavior, like mice socializing together.

Beijing, China — Dec 4, 2022 (CCTV — No access Chinese mainland) 1. Various of ground control team working 2. Screen showing Shenzhou-14 separating from space station combination.

In Space — Dec 4, 2022 (China Manned Space Agency — No access Chinese mainland) 3. Shenzhou-14 spacecraft.

Beijing, China — Dec 4, 2022 (CCTV — No access Chinese mainland) 4. Various of screen showing Shenzhou-14 separating from space station combination 5. Various of screen showing space station combination 6. Screen showing Shenzhou-14 separating from space station combination.

The world’s first artificial liver has been grown from stem cells by British scientists. The resulting “mini-liver” is the size of a small coin; the same technique will be further developed to create a full-size liver.

The mini-liver is useful as it is; within two years it can be used to test new drugs, reducing the number of animal experiments as well as providing results based on a human (rather than animal) liver.

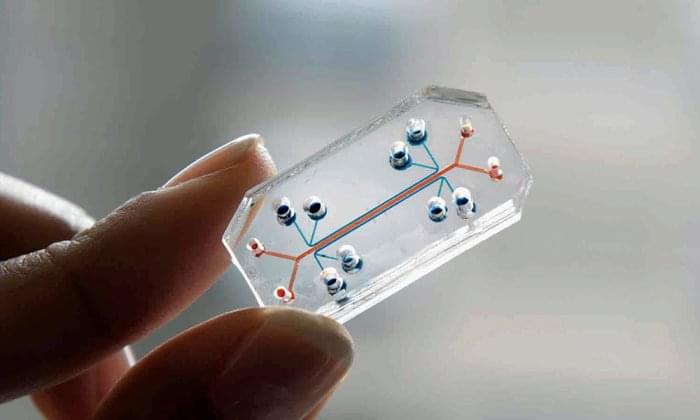

Human pancreas-on-a-chip (PoC) technology is quickly advancing as a platform for complex in vitro modeling of islet physiology. This review summarizes the current progress and evaluates the possibility of using this technology for clinical islet transplantation.

PoC microfluidic platforms have mainly shown proof of principle for long-term culturing of islets to study islet function in a standardized format. Advancement in microfluidic design by using imaging-compatible biomaterials and biosensor technology might provide a novel future tool for predicting islet transplantation outcome. Progress in combining islets with other tissue types gives a possibility to study diabetic interventions in a minimal equivalent in vitro environment.

Although the field of PoC is still in its infancy, considerable progress in the development of functional systems has brought the technology on the verge of a general applicable tool that may be used to study islet quality and to replace animal testing in the development of diabetes interventions.

😗

Not to mention the potential for cost-savings. If you have been severely sick, you will have felt the unfairness of the high cost of drugs. The latest drugs for cancer, cardiovascular or gastrointestinal diseases, nervous disorders, and rare conditions are so costly that even selling an expensive car won’t cover a year’s supply of them.

The most poignant example is that of cancer drugs, whose approval is by far the most wasteful process of all drug types: The FDA approves less than four percent of cancer drugs, meaning 96 percent of them spend more than a decade being tested in petri dishes, mice, and a small set of patients, before scientists finally realize that they aren’t suitable for human use. Each drug in the four percent that does get approved bears an average price tag of more than a billion dollars, a bill passed down to you, the patient-customer.

Given what is at stake, it is not surprising that a growing number of companies are offering their organs-on-chips to pharma, each with a different technology, patented chip design, or organ. The three oldest companies in this space — Hurel Corporation, Hepregen, and Organovo, founded in 2007 — are all from the United States. InSphero (Switzerland, 2009), TissUse (Germany, 2010), and Mimetas (Netherlands, 2011) were started shortly afterward. Nortis (Seattle, 2012) and Emulate (Boston, 2013, by Don Ingber) followed, and after them half a dozen startup companies are fighting to grow in this exciting cauldron. Thanks to the organs-on-chips pioneered by Grotberg, Huh, and Takayama, the day when most new drugs will be developed and tested directly (and only) using human tissues is fast approaching.

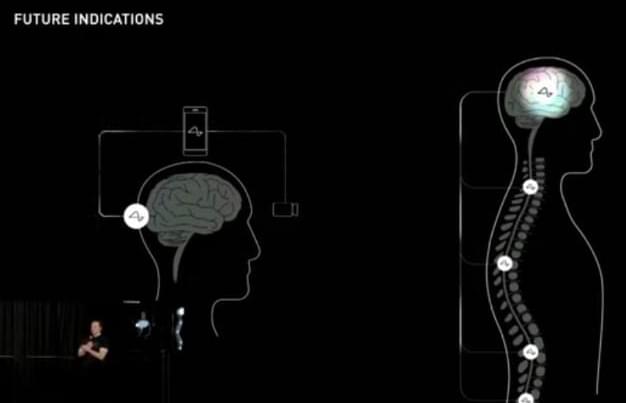

Elon Musk is confident that Neuralink will be able to restore vision in humans who are blind and full body functionality in humans who have a severed spinal cord.

Neuralink, another of Elon Musk’s companies, held its Show & Tell on Wednesday, and many revelations were shared in the live stream. One of those revelations included restoring vision even if someone was born blind. And also restoring full body functionality to someone with a severed spinal cord.

Elon Musk founded Neuralink to answer the question, “What do we do if there is a superintelligence that is much smarter than human beings? How do we, as a species, mitigate the risk or, in a benign scenario, go along for the ride?”