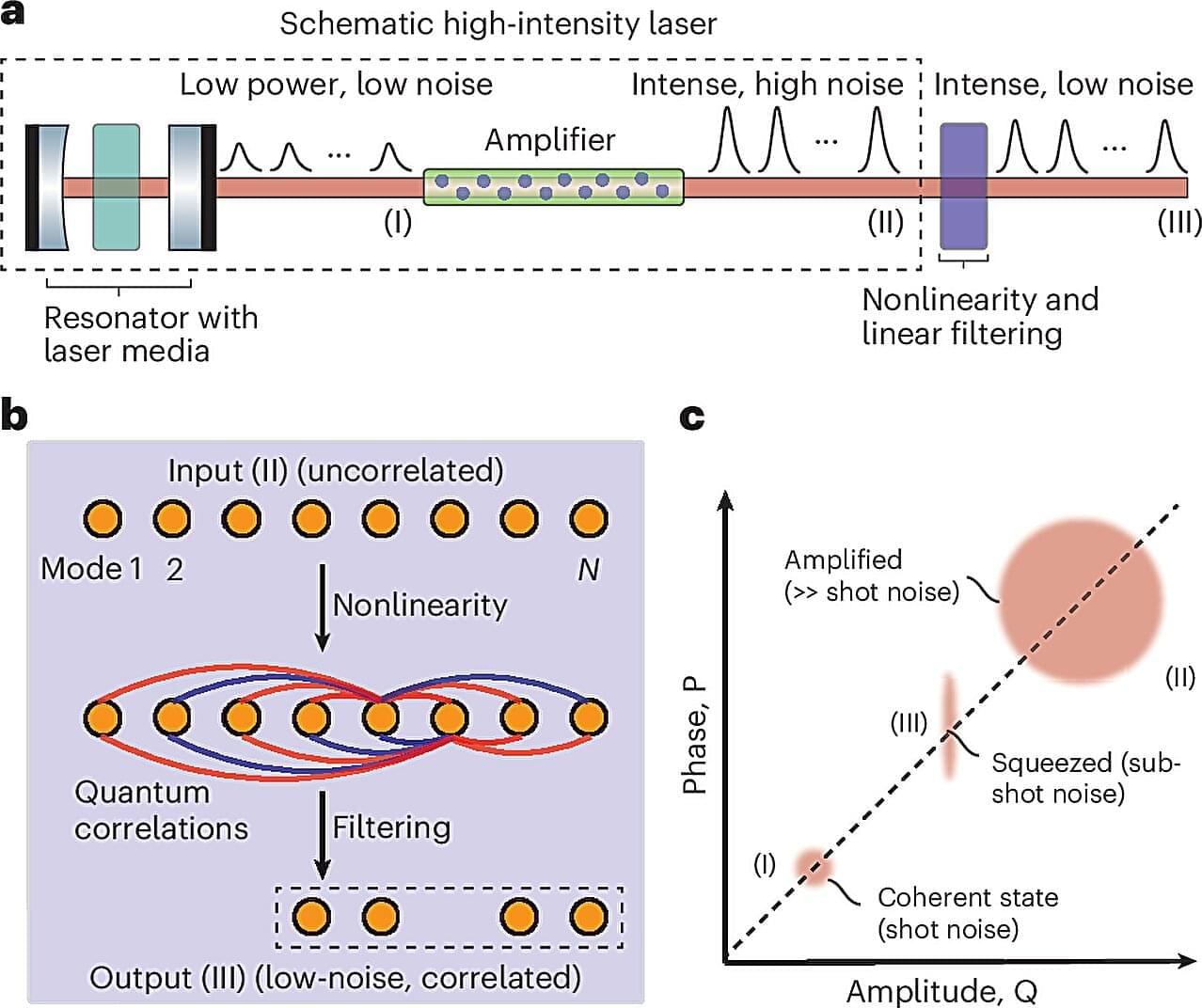

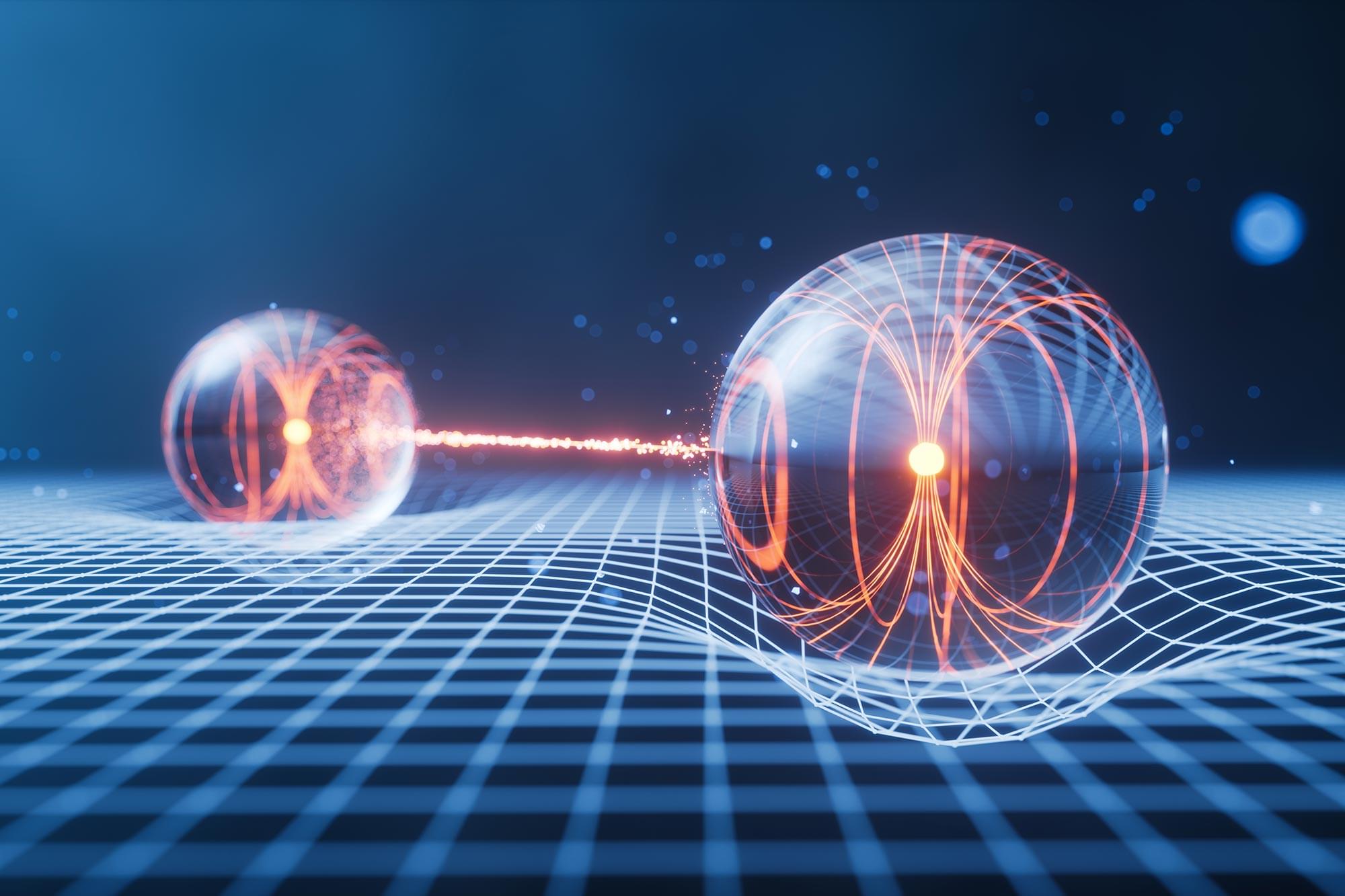

Scientists have discovered a way to convert fluctuating lasers into remarkably stable beams that defy classical physics, opening new doors for photonic technologies that rely on both high power and high precision.

Lasers are essential tools in science, industry and medicine, but increasing their power often results in “noise”—unpredictable fluctuations in intensity that disrupt applications requiring consistent, stable light.

Researchers led by Cornell and the Massachusetts Institute of Technology have demonstrated how noisy, amplified lasers can be transformed into ultra-stable beams through the clever use of optical fibers and filters. The technique was detailed in Nature Photonics.