The ispace lander’s failed touchdown highlights the challenges Moon landings pose, especially for private companies.

Smarter Faster™

► Big Think.

Our mission is to make you smarter, faster. Watch interviews with the world’s biggest thinkers on science, philosophy, business, and more.

► Big Think+

Looking to ignite a learning culture at your company? Prepare your workforce for the future with educational courses from the world’s biggest thinkers. Trusted by Ford, Marriot, Bank of America, and many more. Learn how Big Think+ can empower your people today: https://bigthink.com/plus/?utm_source=youtube&utm_medium=vid…escription.

Want more Big Think?

► Daily editorial features: https://bigthink.com/?utm_source=youtube&utm_medium=video&ut…escription.

► Get the best of Big Think right to your inbox: https://bigthink.com/subscribe/?utm_source=youtube&utm_mediu…escription.

► Facebook: https://bigth.ink/facebook/

► Instagram: https://bigth.ink/Instagram/

► Twitter: https://bigth.ink/twitter/

The Galaxy is approximately 13 billion years old, which makes one wonder — just how many civilizations could have come and gone across that ocean of time? Today, we try something a little bit different for this channel, and imagine when and how the first civilization could have lived. The story is a fiction, but it provides a narrative around which we can more viscerally experience the conditions of the early cosmos, and the fragility of life itself.

Written & presented by Prof David Kipping.

→ Support our research program: https://www.coolworldslab.com/support.

→ Get Stash here! https://teespring.com/stores/cool-worlds-store.

I’ll be speaking at RAND in Santa Monica, March 7th, on the future of space exploration, registration link here: https://www.rand.org/events/2022/03/7-8.html.

THANK-YOU to our supporters D. Smith, M. Sloan, L. Sanborn, C. Bottaccini, D. Daughaday, A. Jones, S. Brownlee, G. Fulton, N. Kildal, M. Lijoi, Z. Star, E. West, T. Zanjonc, C. Wolfred, F. Rebolledo, L. Skov, E. Wilson, A. de Vaal, M. Elliott, B. Daniluk, M. Forbes, S. Vystoropskyi, S. Lee, Z. Danielson, C. Fitzgerald, V. Alexandrov, L. Macchia, C. Souter, M. Gillette, T. Jeffcoat, H. Jensen, F. Linker, J. Rockett, N. Fredrickson, B. Mlazgar, D. Holland, J. Alexander, E. Hanway, J. Molnar, D. Murphree, S. Hannum, T. Donkin, K. Myers, A. Schoen, K. Dabrowski, J. Black, R. Ramezankhani, J. Armstrong, K. Weber, S. Marks, L. Robinson, F. van Exter, S. Roulier, B. Smith, P. Masterson, R. Sievers, G. Canterbury, J. Kill, J. Cassese, J. Kruger, S. Way, P. Finch, S. Applegate, L. Watson, T. Wheeler, E. Zahnle, N. Gebben, B. Weaver, E. Simonson, M. Murru, M. Shea, P. Finch, R. Boots, S. Applegate, L. Watson, S. Netherclift T. Wheeler T. West A. West H. Kissick, C. MacPherson, D. Bayless, D. Rolfe, E. Zahnle & G. Bolloten.

::Music::

And exploration of 10 Unpleasant Alien Civilization Scenarios and speculation on what they might mean.

My Patreon Page:

https://www.patreon.com/johnmichaelgodier.

My Event Horizon Channel:

https://www.youtube.com/eventhorizonshow.

Music:

A Re-Edited version of Aldous Huxleys classic, Brave New World…

My original plan was to only show parts relevent to present times… Then I realised that this is the blue print for our future… And the future is here, now and present… What we do from here is anyones guess… This should be seen by EVERY HUMAN ALIVE… It is the story of our fate and final destruction… We are already at the tipping point… Don’t accept their bullshit… Fight back with NON COMPLIANCE!!! DO NOT ACCEPT 5G… DO NOT ACCEPT BIO-TECHNICS… DO NOT ACCEPT IMPLANTS, VACCINES, NANO-TECH, etc, etc, etc… The future is ours if we take it… Or leave it to the World Rulling Psychopaths… The choice is YOURS!!!

I LOVE YOU ALL!!!

(Stick around at the end for a very real interview with Aldous Huxley where he explains why yesterdays fiction, is tomorrows reality…)

… Please leave your comments or questions bellow. Also check out my other videos and let me know what you think… Unless you think I’m CrAzY… In which case, I seriously don’t suggest watching the other videos… Just don’t do it… It’s for your own good wink (: For more related videos go to my channels playlists to find a huge selection ranging from Music to Movies, News & Political Affairs, Comedy, Wrestling, Documentaries & loads more… Thanks for watching smile

Want more madness??? (: CLICK SUBSCRIBE smile # @ );?! % £ $ € %!? ;(@ #…

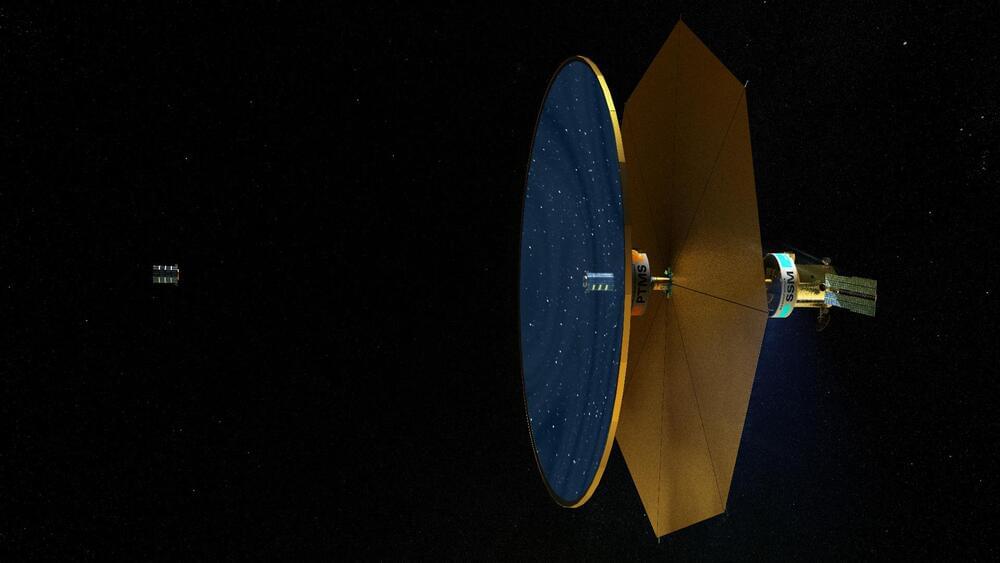

The Fluidic Telescope (FLUTE) project team, jointly led by NASA and Technion–Israel Institute of Technology, envisions a way to make huge circular self-healing mirrors in-orbit to further the field of astronomy. Larger telescopes collect more light, and they allow astronomers to peer farther into space and see distant objects in greater detail.

These next-generation large space observatories would study the highest priority astrophysics targets, including first generation stars—the first to shine and flame out after the Big Bang—early galaxies, and Earth-like exoplanets. These observatories could help address one of humanity’s most important science questions: “Are we alone in the universe?”

Like a carry-on suitcase, payloads launching to space need to stay within allowable size and weight limits to fly. Already pushing size limits, the state-of-the-art 21 foot (6.5 meter) aperture James Webb Space Telescope needed to be folded up origami-style—including the mirror itself—to fit inside the rocket for its ride to space. The aperture of an optical space observatory refers to the size of the telescope’s primary mirror, the surface that collects and focuses incoming light.

Humanity has had a sustained human presence in space for decades now. Traveling the world can be done in mere hours, and each of us carries within our pockets a supercomputer that is linked to all of human knowledge. Our fingertips are now more powerful than the kings or queens of centuries past. For all of our flaws and challenges, we live in the protopia today.

Not dystopia, not utopia, but something else.

Po-Shen Loh (Carnegie Mellon University)https://simons.berkeley.edu/events/theoretically-speaking-bu…ation-chat…