Year 2019 face_with_colon_three

In greenhouses across China, scientists are exposing lettuces and cucumbers to powerful electric fields in an attempt to make them grow faster. Can electroculture work?

It’s possibly the most famous question in all of science — where is everyone? Join us today for deep dive into Fermi Paradox.

Thanks to NordVPN for sponsoring this episode. 🌏 Get exclusive NordVPN deal here ➵ https://NordVPN.com/coolworlds It’s risk free with Nord’s 30 day money-back guarantee!✌

The Fermi Paradox has been a topic of keen debate amongst scientists, astronomers and the rest of us for more than seven decades. We can’t resist the urge to speculate about aliens! But what is the paradox even really about? What explanations have been offered? Today, we explore this famous question, and offer a mind-shifting explanation.

Written and presented by Prof David Kipping, guest starring Jackson Kipping and edited by Jorge Casas.

→ Support our research program: https://www.coolworldslab.com/support.

→ Get Stash here! https://teespring.com/stores/cool-worlds-store.

THANK-YOU to our supporters D. Smith, M. Sloan, C. Bottaccini, D. Daughaday, A. Jones, S. Brownlee, N. Kildal, Z. Star, E. West, T. Zajonc, C. Wolfred, L. Skov, G. Benson, A. De Vaal, M. Elliott, B. Daniluk, M. Forbes, S. Vystoropskyi, S. Lee, Z. Danielson, C. Fitzgerald, C. Souter, M. Gillette, T. Jeffcoat, J. Rockett, D. Murphree, S. Hannum, T. Donkin, K. Myers, A. Schoen, K. Dabrowski, J. Black, R. Ramezankhani, J. Armstrong, K. Weber, S. Marks, L. Robinson, S. Roulier, B. Smith, G. Canterbury, J. Cassese, J. Kruger, S. Way, P. Finch, S. Applegate, L. Watson, E. Zahnle, N. Gebben, J. Bergman, E. Dessoi, J. Alexander, C. Macdonald, M. Hedlund, P. Kaup, C. Hays, W. Evans, D. Bansal, J. Curtin, J. Sturm, RAND Corp., M. Donovan, N. Corwin, M. Mangione, K. Howard, L. Deacon, G. Metts, G. Genova, R. Provost, B. Sigurjonsson, G. Fullwood, B. Walford, J. Boyd, N. De Haan, J. Gillmer, R. Williams, E. Garland, A. Leishman, A. Phan Le, R. Lovely, M. Spoto, A. Steele, M. Varenka, K. Yarbrough, A. Cornejo, D. Compos, F. Demopoulos, G. Bylinsky, J. Werner, B. Pearson, S. Thayer & T. Edris.

Sourcing human tissue samples for biological investigations isn’t always easy. While they are ethically obtained through organ donation or from tissue that’s removed during surgical procedures, scientists are finding them increasingly difficult to get hold of.

And it’s not just because there’s a limited supply of human tissue samples. There’s also restricted availability of the specific size and type of tissue samples needed for the many projects taking place at any given time.

That’s why we decided to address the issue by building our own low-cost, easily accessible printer capable of creating human tissue samples using one of the world’s most popular toys.

Lead author Jon Walbrin explains, “Most previous social neuroscience studies have focused on measuring responses to other people as individuals. But more recently there has been an increased interest in understanding brain responses to others in the context of social interactions. However, very little is currently known about how such responses develop during childhood.”

“These results suggest that children and adults might employ different strategies for interaction understanding: Adults rely more on observable, body-based information, while children—with less social experience—engage more in effortful reasoning about what others are thinking and feeling during an interaction. This likely reflects the process of learning to understand interactive behavior.”

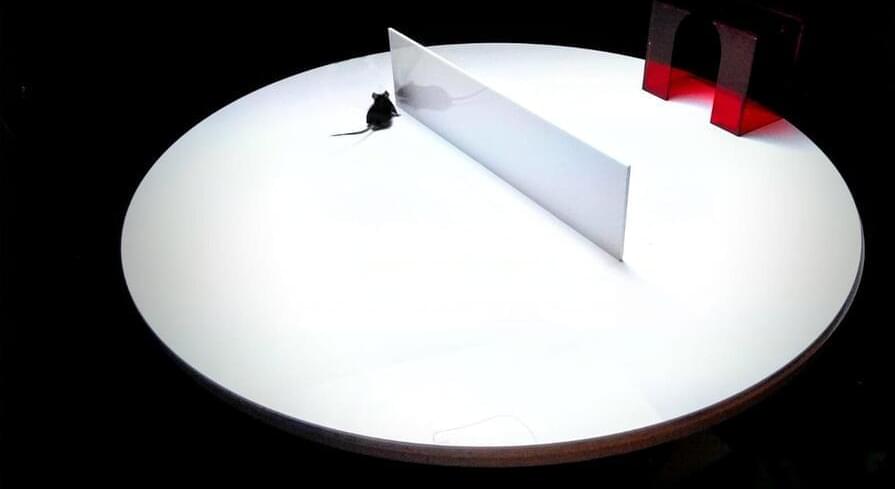

Neuroscientists have uncovered how exploratory actions enable animals to learn their spatial environment more efficiently. Their findings could help build better AI agents that can learn faster and require less experience.

Researchers at the Sainsbury Wellcome Center and Gatsby Computational Neuroscience Unit at UCL found the instinctual exploratory runs that animals carry out are not random. These purposeful actions allow mice to learn a map of the world efficiently. The study, published today, April 28, in Neuron, describes how neuroscientists tested their hypothesis that the specific exploratory actions that animals undertake, such as darting quickly towards objects, are important in helping them learn how to navigate their environment.

“There are a lot of theories in psychology about how performing certain actions facilitates learning. In this study, we tested whether simply observing obstacles in an environment was enough to learn about them, or if purposeful, sensory-guided actions help animals build a cognitive map of the world,” said Professor Tiago Branco, Group Leader at the Sainsbury Wellcome Center and corresponding author on the paper.

Quantum objects make up classical objects. But the two behave very differently. The collapse of the wave-function prevents classical objects from doing the weird things quantum objects do; like quantum entanglement or quantum tunneling. Is the universe as a whole a quantum object or a classical one? Artyom Yurov and Valerian Yurov argue the universe is a quantum object, interacting with other quantum universes, with surprising consequences for our theories about dark matter and dark energy.

1. The Quantum Wonderland

If scientific theories were like human beings, the anthropomorphic quantum mechanics would be a miracle worker, a brilliant wizard of engineering, capable of fabricating almost anything, be it a laser or a complex integrated circuit. At the same token, this wizard of science would probably look and act crazier than a March Hair and Mad Hatter combined. The fact of the matter is, the principles of quantum mechanics are so bizarre and unintuitive, they seem to be utterly incompatible with our inherent common sense. For example, in the quantum realm, a particle does not journey from point A to point B along some predetermined path. Instead, it appears to traverse all possible trajectories between these points – every single one! In this strange realm the items might vanish right in front of an impenetrably high barrier – only to materialize on the other side (this is called quantum tunneling).

Most of the matter and energy in the Universe are in mysterious, invisible forms that cannot be explained by physics as we know it. But it is possible for us to uncover the dark side of the Universe, and CERN physicist John Ellis knows how.

John Ellis is a Maxwell prize-winning theoretical physicist, and is considered one of the world’s leading physicists. John is currently Clerk Maxwell Professor of Theoretical Physics at King’s College London, and since 1978 has held an indefinite contract at CERN.