© 1998 — 2023 Nexstar Media Group Inc. | All Rights Reserved.

\t\t\t\t.

\t.

\t\t.

\t\tTrending on NewsNation.

\t\t.

\t.

For thousands of years, mathematicians have adapted to the latest advances in logic and reasoning. Are they ready for artificial intelligence?

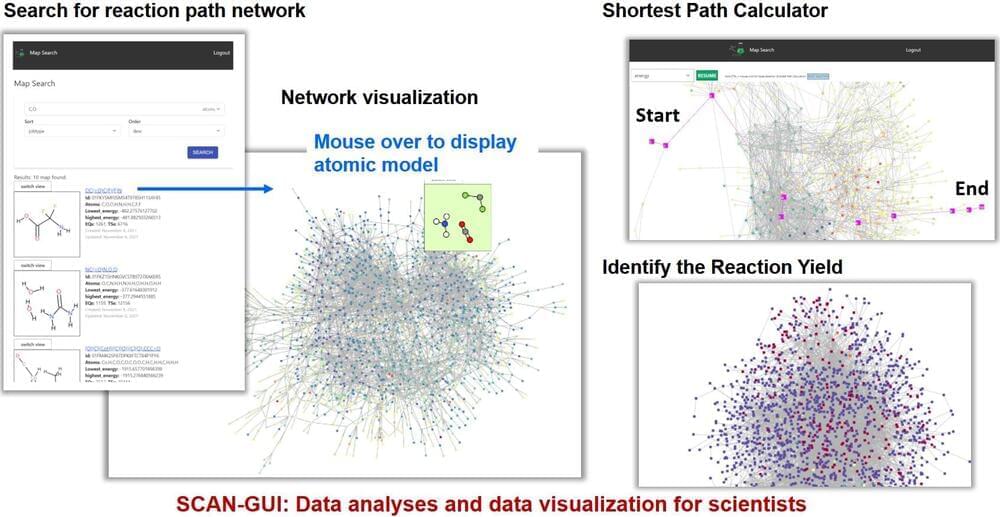

A new online platform to explore computationally calculated chemical reaction pathways has been released, allowing for in-depth understanding and design of chemical reactions.

Advances in computational chemistry have lead to the discovery of new reaction pathways for the synthesis of high-value compounds. Computational chemistry generates much data, and the process of organizing and visualizing this data is vital to be able to utilize it for future research.

A team of researchers from Hokkaido University, led by Professor Keisuke Takahashi at the Faculty of Chemistry and Professor Satoshi Maeda at the Institute for Chemical Reaction Design and Discovery (WPI-ICReDD), have developed a centralized, interactive, and user-friendly platform, Searching Chemical Action and Network (SCAN), to explore reaction pathways generated by computational chemistry. Their research was published in the journal Digital Discovery.

Humans split away from our closest animal relatives, chimpanzees, and formed our own branch on the evolutionary tree about seven million years ago. In the time since—brief, from an evolutionary perspective—our ancestors evolved the traits that make us human, including a much bigger brain than chimpanzees and bodies that are better suited to walking on two feet. These physical differences are underpinned by subtle changes at the level of our DNA. However, it can be hard to tell which of the many small genetic differences between us and chimps have been significant to our evolution.

New research from Whitehead Institute Member Jonathan Weissman; University of California, San Francisco Assistant Professor Alex Pollen; Weissman lab postdoc Richard She; Pollen lab graduate student Tyler Fair; and colleagues uses cutting edge tools developed in the Weissman lab to narrow in on the key differences in how humans and chimps rely on certain genes. Their findings, published in the journal Cell on June 20, may provide unique clues into how humans and chimps have evolved, including how humans became able to grow comparatively large brains.

In a groundbreaking study, researchers from Weill Cornell Medicine and the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute, a department of the National Institutes of Health.

The National Institutes of Health (NIH) is the primary agency of the United States government responsible for biomedical and public health research. Founded in 1,887, it is a part of the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services. The NIH conducts its own scientific research through its Intramural Research Program (IRP) and provides major biomedical research funding to non-NIH research facilities through its Extramural Research Program. With 27 different institutes and centers under its umbrella, the NIH covers a broad spectrum of health-related research, including specific diseases, population health, clinical research, and fundamental biological processes. Its mission is to seek fundamental knowledge about the nature and behavior of living systems and the application of that knowledge to enhance health, lengthen life, and reduce illness and disability.

Whether it’s baking a cake, constructing a building, or creating a quantum device, the caliber of the finished product is greatly influenced by the components or fundamental materials used. In their pursuit to enhance the performance of superconducting qubits, which form the bedrock of quantum computers, scientists have been probing different foundational materials aiming to extend the coherent lifetimes of these qubits.

Coherence time serves as a metric to determine the duration a qubit can preserve quantum data, making it a key performance indicator. A recent revelation by researchers showed that the use of tantalum in superconducting qubits enhances their functionality. However, the underlying reasons remained unknown – until now.

Scientists from the Center for Functional Nanomaterials (CFN), the National Synchrotron Light Source II (NSLS-II), the Co-design Center for Quantum Advantage (C2QA), and Princeton University investigated the fundamental reasons that these qubits perform better by decoding the chemical profile of tantalum.

An android robot, EveR 6, took the conductor’s podium in Seoul on Friday evening to lead a performance by South Korea’s national orchestra, marking the first such attempt in the country.

The two-armed robot, designed by the Korea Institute of Industrial Technology, made its debut at the National Theater of Korea, leading musicians in the country’s national orchestra.

The robot, with a humanoid face, first bowed to the audience and started waving its arms to control the tempo of the live show.

The concept of a computational consciousness and the potential impact it may have on humanity is a topic of ongoing debate and speculation. While Artificial Intelligence (AI) has made significant advancements in recent years, we have not yet achieved a true computational consciousness that can replicate the complexities of the human mind.

It is true that AI technologies are becoming more sophisticated and capable of performing tasks that were previously exclusive to human intelligence. However, there are fundamental differences between Artificial Intelligence and human consciousness. Human consciousness is not solely based on computation; it encompasses emotions, subjective experiences, self-awareness, and other aspects that are not yet fully understood or replicated in machines.

The arrival of advanced AI systems could certainly have transformative effects on society and our understanding of humanity. It may reshape various aspects of our lives, from how we work and communicate to how we approach healthcare and scientific discoveries. AI can enhance our capabilities and provide valuable tools for solving complex problems.

However, it is important to consider the ethical implications and potential risks associated with the development of AI. Ensuring that AI systems are developed and deployed responsibly, with a focus on fairness, transparency, and accountability, is crucial.