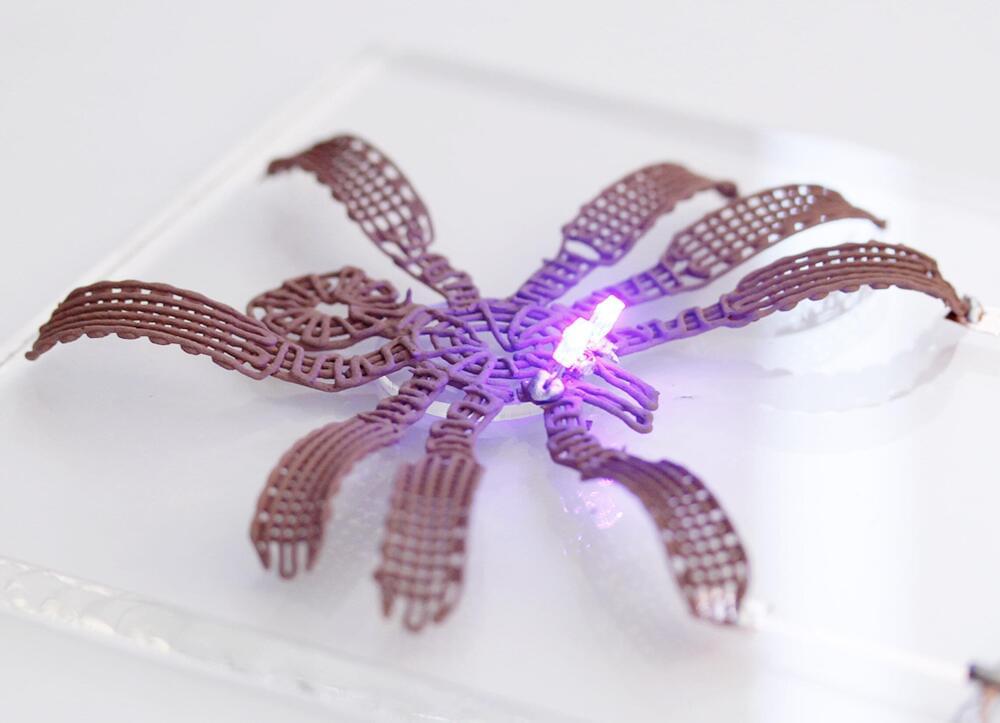

Researchers have developed a metallic gel that is highly electrically conductive and can be used to print three-dimensional (3D) solid objects at room temperature. The paper, “Metallic Gels for Conductive 3D and 4D Printing,” has been published in the journal Matter.

“3D printing has revolutionized manufacturing, but we’re not aware of previous technologies that allowed you to print 3D metal objects at room temperature in a single step,” says Michael Dickey, co-corresponding author of a paper on the work and the Camille & Henry Dreyfus Professor of Chemical and Biomolecular Engineering at North Carolina State University. “This opens the door to manufacturing a wide range of electronic components and devices.”

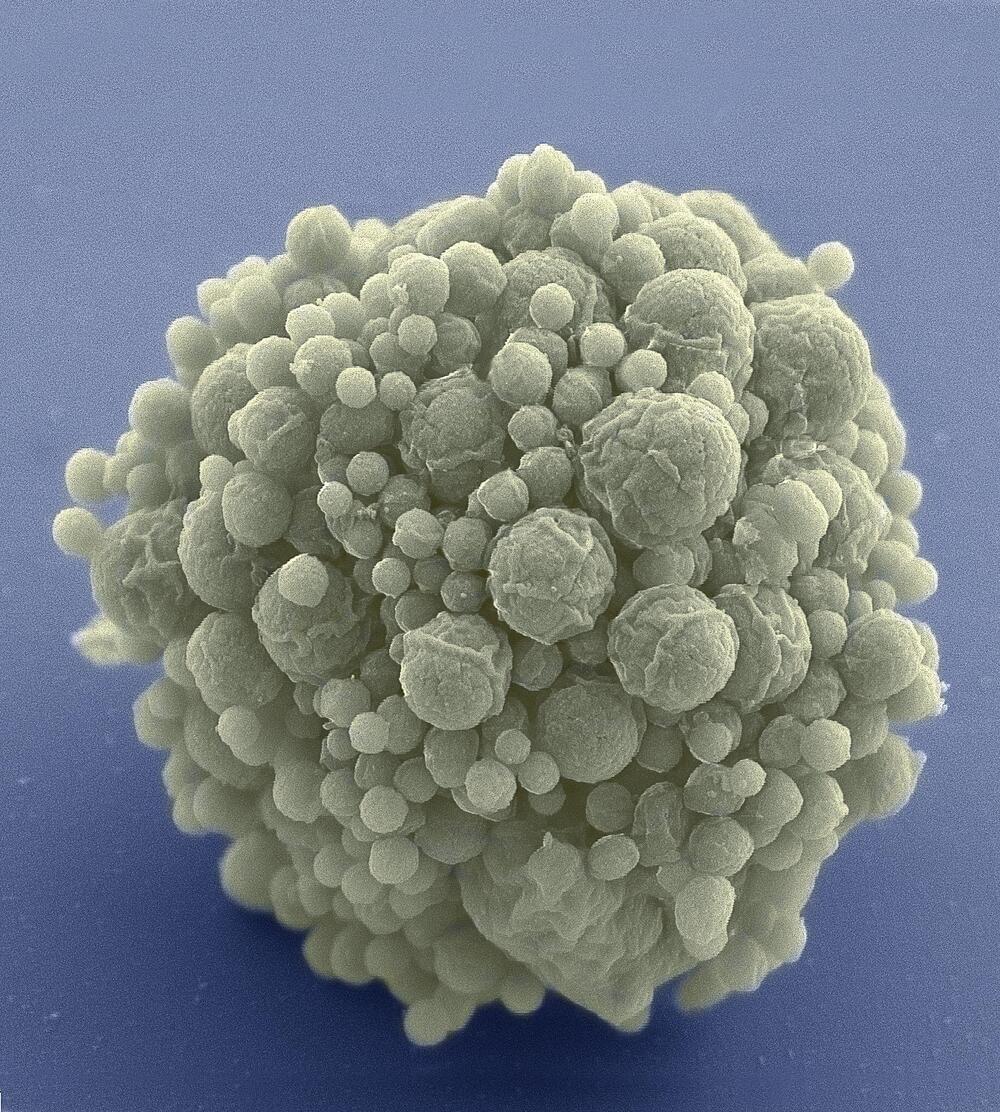

To create the metallic gel, the researchers start with a solution of micron-scale copper particles suspended in water. The researchers then add a small amount of an indium-gallium alloy that is liquid metal at room temperature. The resulting mixture is then stirred together.