My ninth installment of interesting research papers that I have read over the past few weeks and would like to share with my community.

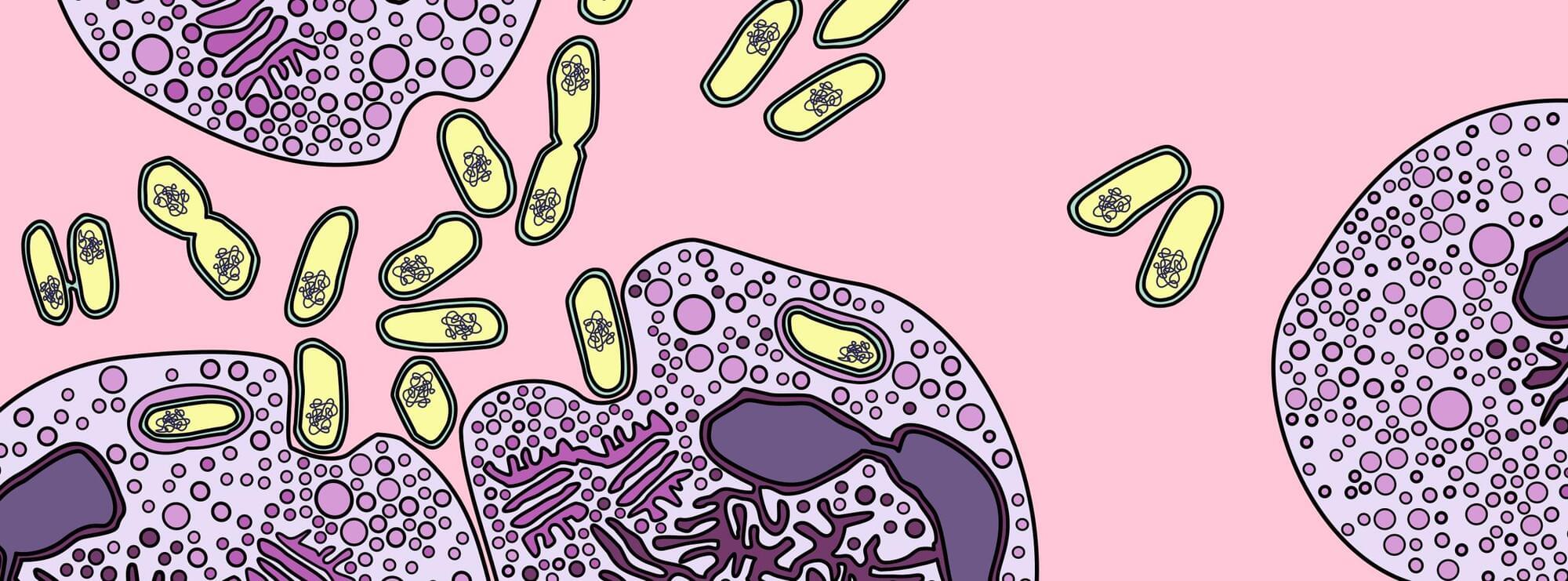

Chimeric antigen receptor (CAR) macrophages may represent a promising anti-cancer immune therapy strategy due to their favourable biological properties but in vitro manipulation and targeting to specific organs could be challenging. Here authors use inhalable small extracellular vesicles to deliver the CAR mRNA construct to macrophages in the lung and show that the thus in situ generated CAR macrophages successfully combat lung metastasis and cancer recurrence in a mouse model.

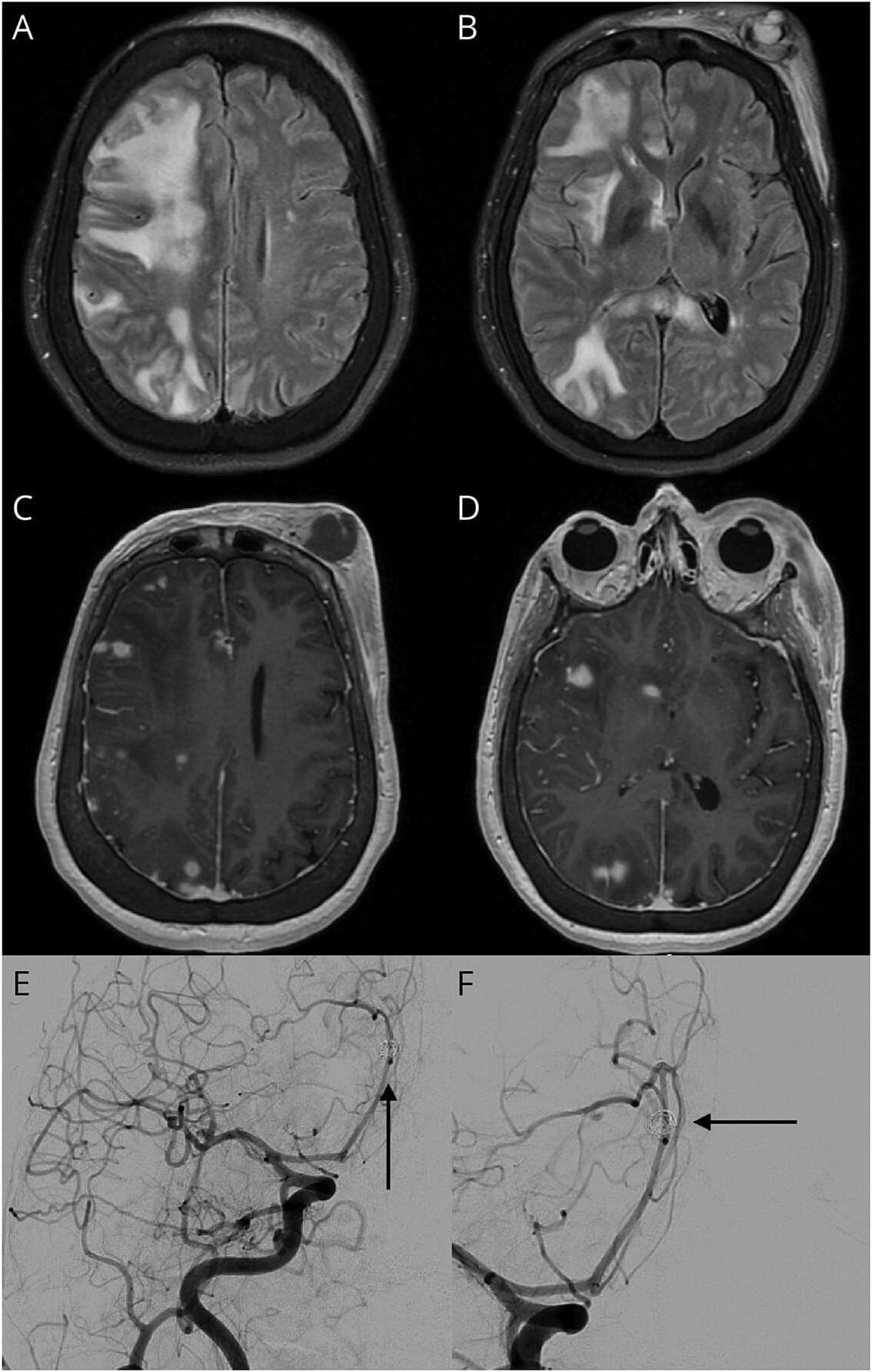

Superficial vein thrombosis is a condition in which blood clots develop within the superficial veins (close to the skin surface), typically in the legs or arms.

Common risk factors for superficial vein thrombosis are varicose veins, pregnancy and up to 12 weeks postpartum, recent trauma, surgery or immobility, and cancer.

This JAMA Patient Page describes superficial vein thrombosis and its risk factors, symptoms, diagnosis, and treatments.

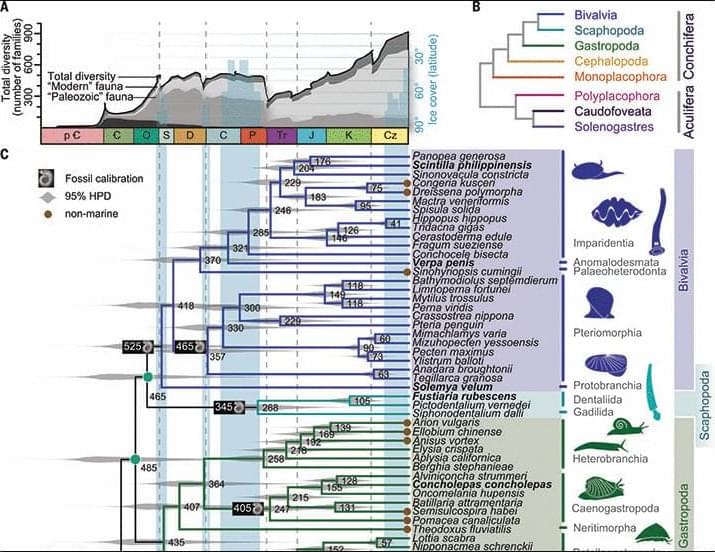

Extreme morphological disparity within Mollusca has long confounded efforts to reconstruct a stable backbone phylogeny for the phylum. Familiar molluscan groups—gastropods, bivalves, and cephalopods—each represent a diverse radiation with myriad morphological, ecological, and behavioral adaptations. The phylum further encompasses many more unfamiliar experiments in animal body-plan evolution. In this work, we reconstructed the phylogeny for living Mollusca on the basis of metazoan BUSCO (Benchmarking Universal Single-Copy Orthologs) genes extracted from 77 (13 new) genomes, including multiple members of all eight classes with two high-quality genome assemblies for monoplacophorans. Our analyses confirm a phylogeny proposed from morphology and show widespread genomic variation.

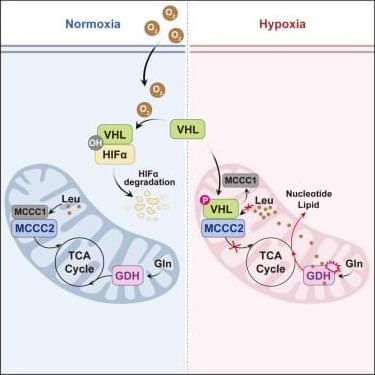

Online now: Li et al. report that under chronic hypoxia, VHL relocates to the mitochondria to rewire amino acid metabolism. Mitochondrial VHL enhances nucleotide and lipid production by blocking leucine breakdown, revealing an unexpected role for VHL in supporting hypoxic cell growth and regulating the progression of hypoxia-related diseases.

The Letters section represents an opportunity for ongoing author debate and post-publication peer review. View our submission guidelines for Letters to the Editor before submitting your comment.

At first glance, the idea sounds implausible: a computer made not of silicon, but of living brain cells. It’s the kind of concept that seems better suited to science fiction than to a laboratory bench. And yet, in a few research labs around the world, scientists are already experimenting with computers that incorporate living human neurons. Such computers are now being trained to perform complex tasks such as play games and even drive robots.

These systems are built from brain organoids: tiny, lab-grown clusters of human neurons derived from stem cells. Though often nicknamed “mini-brains,” they are not thinking minds or conscious entities. Instead, they are simplified neural networks that can be interfaced with electronics, allowing researchers to study how living neurons process information when placed in a computational loop.

In fact, some researchers even claim that these tools are pushing the frontiers of medicine, along with those of computing. Dr. Ramon Velaquez, a neuroscientist from Arizona State University, is one such researcher.

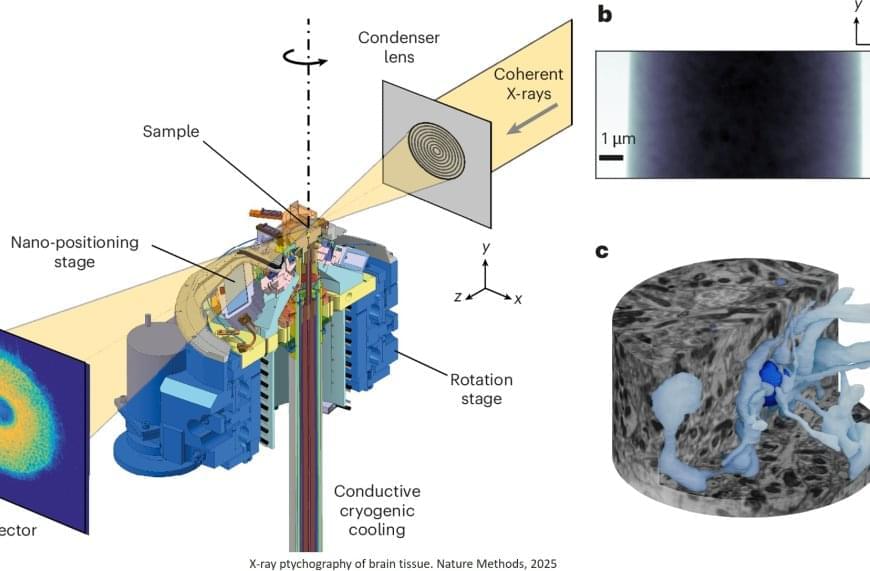

“The brain is one of the most complex biological systems in the world,” says one of the senior authors. How neurons are wired together is what his group are trying to unravel – a field known as connectomics.

The author explains: “Take the liver: we know of about 40 cell types. We know how they are arranged. We know their functions. This is not true for the brain. And so, one could ask, what is the difference between the brain and the liver? If we look at a cell body in the brain and the liver, it’s not easy to distinguish the two. They both have a nucleus, an endoplasmic reticulum – they both have the same intercellular machinery, the same molecules, the same types of proteins. This is not the difference. What is really different is how the brain cells are organised and connected.”

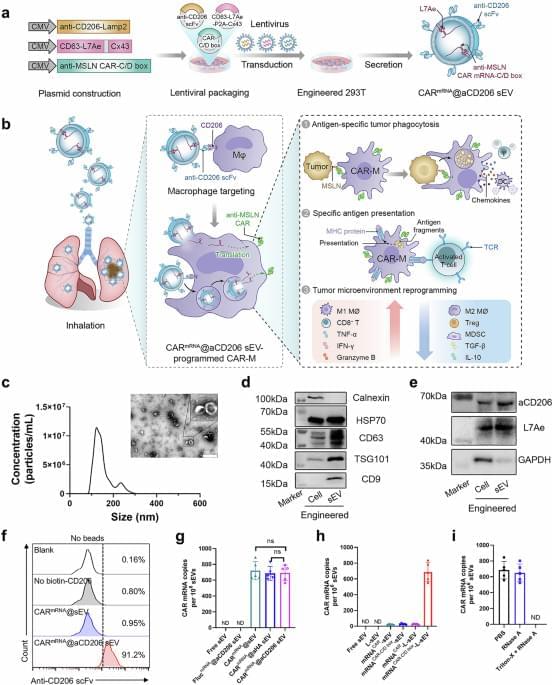

Let’s talk numbers: in one cubic millimetre of brain tissue there are about 100 000 neurons, connected through about 700 million synapses and 4 kilometres of ‘cabling’