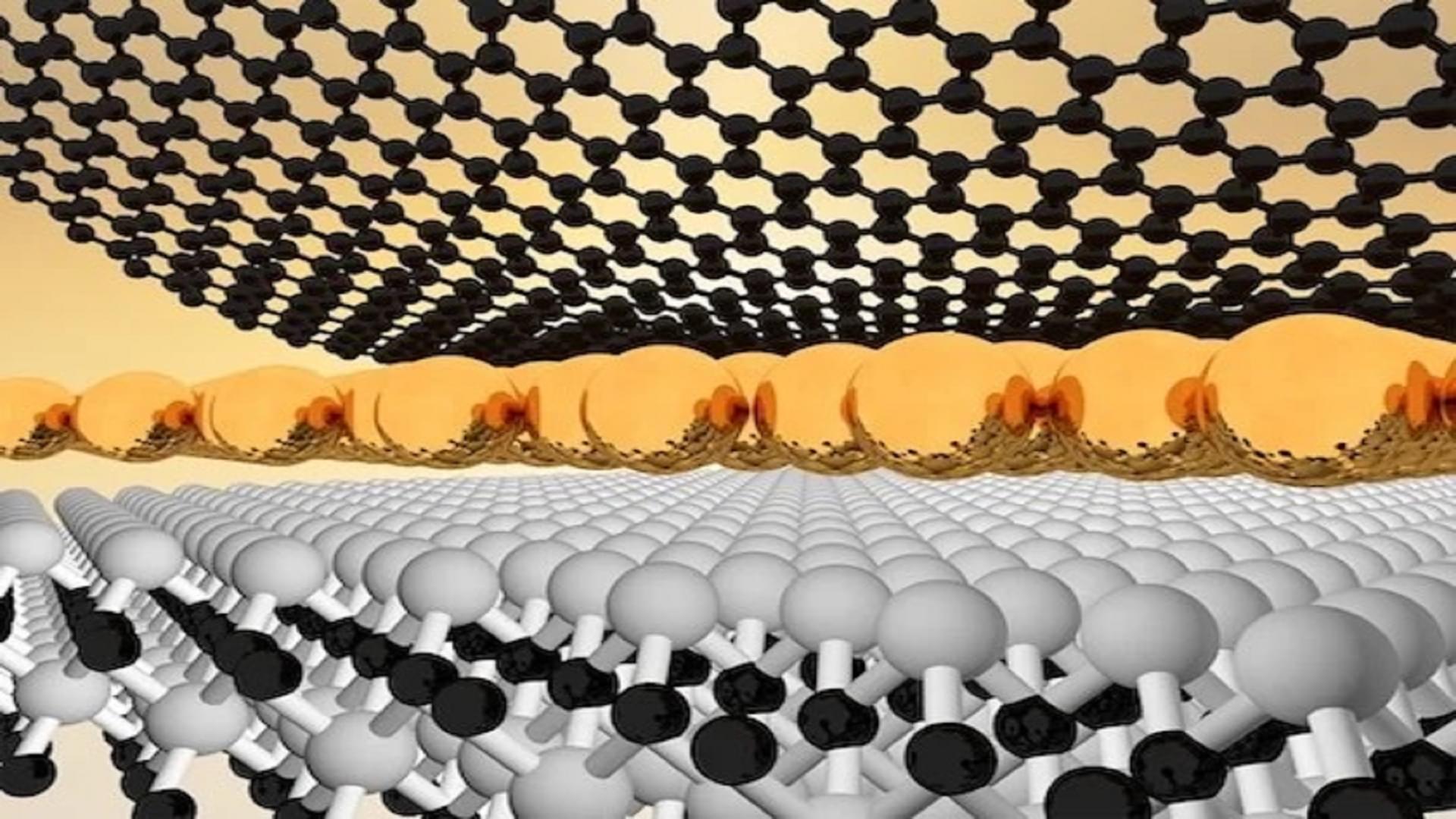

Phonon interference hits new heights, promising leaps in quantum and energy tech.

Rice researchers achieve record phonon interference, opening new paths in quantum sensing and advanced molecular detection.

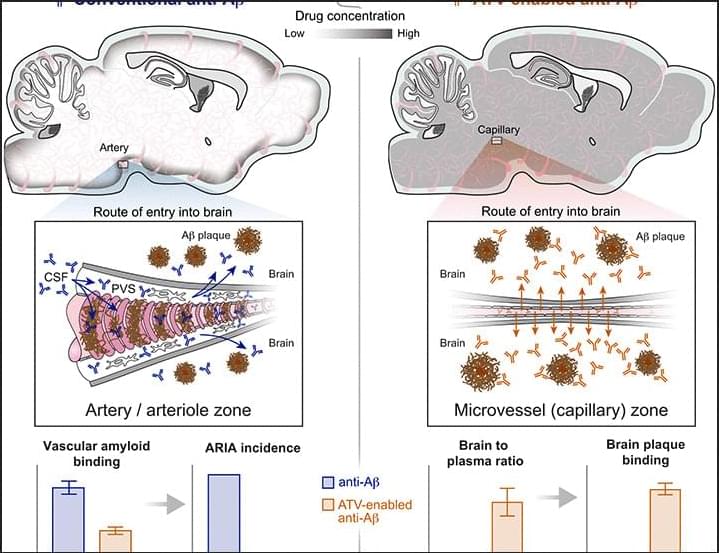

Paper on a promising Alzheimer’s immunotherapy: engineered asymmetric anti-amyloid-β antibody with a transferrin receptor binding domain for crossing the blood-brain-barrier and a mutation which mitigates harmful side effects seen in past versions of this type of treatment. #immunotherapy #alzheimers

Amyloid-related imaging abnormalities (ARIA), side effects of anti-amyloid drugs seen in magnetic resonance imaging of the brain, are a major safety concern in patients with Alzheimer’s disease. We developed an antibody transport vehicle (ATV) targeting transferrin receptor (TfR) for brain delivery of anti-amyloid-β protein (anti-Aβ) using asymmetrical Fc mutations (ATVcisLALA) that mitigates TfR-related liabilities and retains effector function when bound to Aβ. Administration of ATVcisLALA:Aβ in mice exhibited broad brain distribution and enhanced parenchymal plaque target engagement. This biodistribution reduced ARIA-like lesions and vascular inflammation. Taken together, ATVcisLALA has the potential to improve the next generation of Aβ immunotherapy through enhanced biodistribution mediated by transport across the blood-brain barrier.

Peter H. Diamandis

The rapid advancement of artificial intelligence (AI) and machine learning systems has increased the demand for new hardware components that could speed up data analysis while consuming less power. As machine learning algorithms draw inspiration from biological neural networks, some engineers have been working on hardware that also mimics the architecture and functioning of the human brain.

An equation, perhaps no more than one inch long, that would allow us to, quote, ‘Read the mind of God.’

Saudi find may reveal how humans harnessed early dogs to survive