Molecular physiology; Cancer.

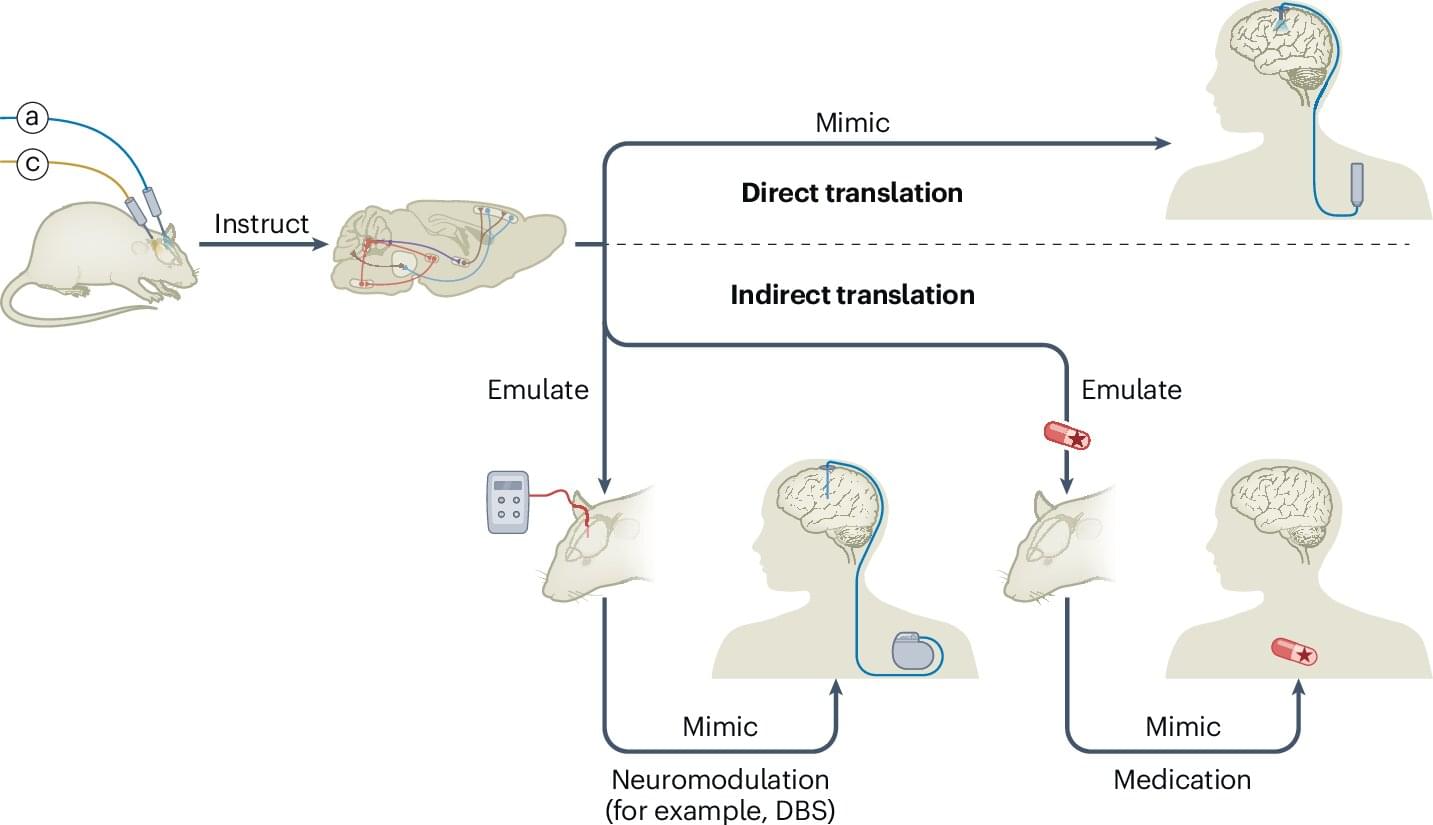

Researchers at the University of Geneva, together with colleagues in Switzerland, France, the United States and Israel, describe how optogenetic control of brain cells and circuits is already steering both indirect neuromodulatory therapies and first-in-human retinal interventions for blindness, while sketching the practical and ethical conditions needed for wider clinical use.

Optogenetic control uses light to impose temporally precise gain or loss of function in specific cell types, or even individual cells. Selected by location, connections, gene expression or combinations of these features, researchers now have an unprecedented way to investigate the brain within living animals.

Modern experiments range from implanted fiber optics to three-dimensional holographic illumination of defined neuronal ensembles and noninvasive wearable LEDs, with interventions that can run from milliseconds to chronic use and effect sizes that change rapidly with changes in light intensity.

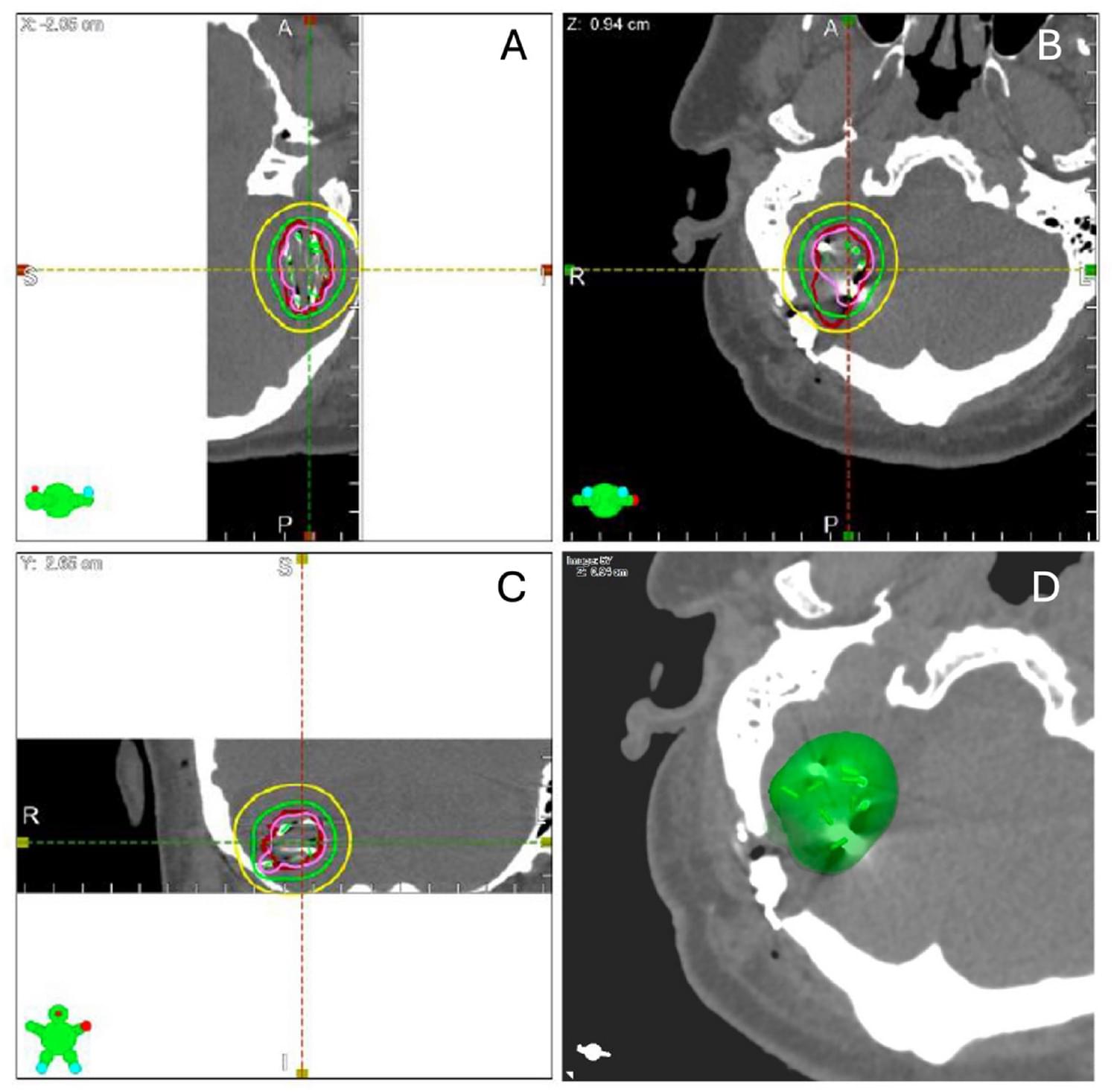

Mahapatra et al. show how minimally invasive keyhole craniotomy combined with brachytherapy provides strong local control for brain metastases, with no radiation necrosis and improved neurological and cognitive outcomes, highlighting this approach as a promising alternative to WBRT and SRS. JNOO

Read more here.

Metastatic brain tumors (MBTs) are the most common intracranial tumors, affecting up to 40% of cancer patients. Traditional treatments such as Whole Brain Radiotherapy (WBRT) and Stereotactic Radiosurgery (SRS) have limitations, including neurocognitive decline and potential tumor regrowth. Minimally invasive keyhole craniotomy (MIKC) and Cesium-131 (Cs-131) brachytherapy offer promising alternatives due to their precision and reduced side effects. This prospective study aims to evaluate the safety and efficacy of combining MIKC with Cs-131 brachytherapy in treating newly diagnosed brain oligometastases.

Twenty-one adults with newly diagnosed brain metastases were enrolled from 2019 to 2021. Preoperative T1 MRI with gadolinium was used to calculate the gross tumor volume (GTV). Minimally invasive craniotomies were performed with resection of these tumors, followed by the implantation of Cs-131 seeds. Postoperative imaging was conducted to verify seed placement and resection. Dosimetric values (V100, V200, D90) were calculated. Patients were followed every two months for two years to monitor local progression, functional outcomes, and quality of life. The primary endpoint was freedom from local progression, with secondary endpoints including overall survival, functional outcomes, quality of life, and treatment-related complications.

The median preoperative tumor volume was 10.65 cm3, reducing to a resection cavity volume of 6.05 cm3 post-operatively. Dosimetric analysis showed a median V100 coverage of 93.2%, V200 of 43.9%, and D90 of 89.8 Gy. The 1-year local freedom from progression (FFP) was 91.67%, while the distant FFP was 53.91%. Five patients remained alive at the study’s end, with a median survival duration of 5.9 months, a duration likely impacted by the concurrent COVID-19 pandemic. Only one patient experienced local recurrence, and no cases of radiation necrosis were observed. Significant improvements were seen in neurological, functional, and cognitive symptoms.

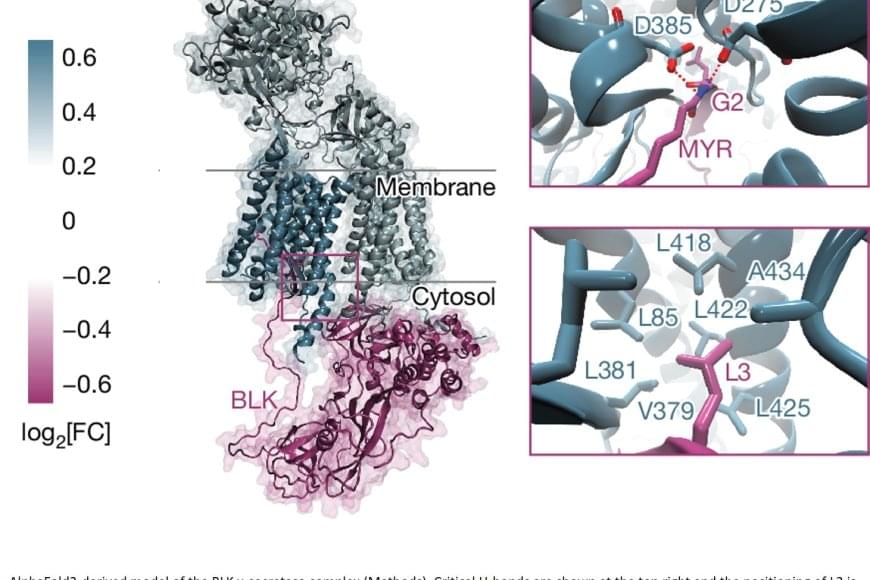

In humans, the loss of thymic function through thymectomy, environmental challenges, or age-dependent involution is associated with increased mortality, inflammaging, and higher risk of cancer and autoimmune disease (1). This is largely due to a decline in the intrathymic naïve T cell pool, whose generation is orchestrated by the thymic stroma, particularly thymic epithelial cells (TECs) (2). Upon challenges that affect the TEC compartment, the thymus is capable of triggering an endogenous regenerative response by engaging resident epithelial progenitors with stem cell features (3–5). Yet, after age-related atrophy or thymectomy resulting from myasthenia gravis or tumor removal (1), this regenerative response is unable to overcome the loss of thymic tissue, highlighting the need for therapeutic interventions.

The restoration of thymic functionality has been achieved to a limited extent via strategies targeting the thymic epithelial microenvironment or hematopoietic progenitors, modulating hormones and metabolism, or through cellular therapies and bioengineering (6). In mice, the up-regulation of Foxn1, a key transcription factor for thymus development and organogenesis (7), either directly or via its upstream effector bone morphogenetic protein 4 (BMP4), can support activity of cortical TECs (cTECs) (8, 9). Further, a combination of growth hormone and metformin has been shown to restore thymic functional mass in humans (10). Nevertheless, such strategies only lead to delayed thymic involution, and examples of complete thymus regeneration have not yet been described among vertebrates.

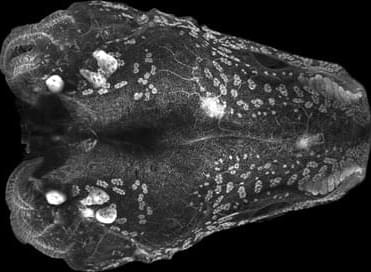

Because of its remarkable regenerative abilities that extend to parts of the brain, eye, heart, and spinal cord, and even entire limbs, the axolotl (Ambystoma mexicanum) is a powerful model for regeneration studies (11). The axolotl has offered insights into the mechanisms of positional identity (12), cell plasticity (13, 14), and the molecular basis of complex regeneration (15–18). The regeneration of axolotl body parts relies on remnants of the missing structure, with the exception of lens tissue, which can regrow from dorsal pigmented epithelial cells during a short window during development (19). However, whether de novo regeneration can occur for an entire complex organ, in axolotls or any other vertebrate, is unknown.

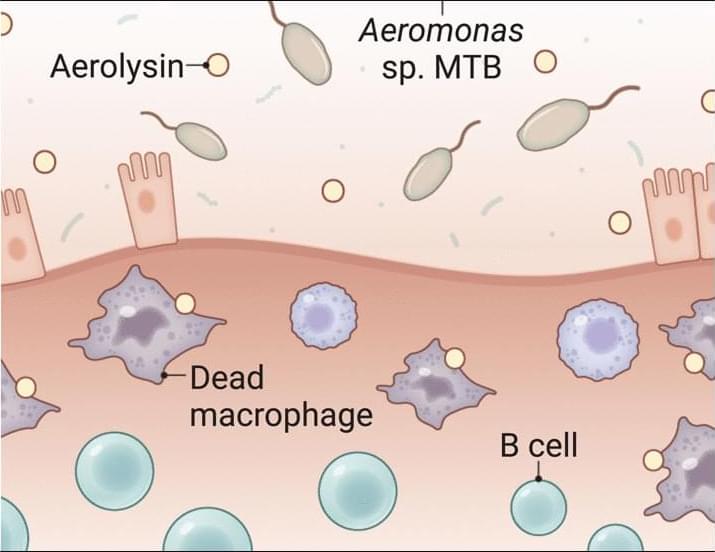

A toxin-secreting gut bacterium may fuel ulcerative colitis by killing protective immune cells that maintain intestinal homeostasis, according to a new study in Science. The findings suggest potential for new treatment strategies.

Learn more in a new Science Perspective.

Macrophage-toxic bacteria from patients with ulcerative colitis worsen gut inflammation in mice.

Sonia Modilevsky and Shai Bel Authors Info & Affiliations

Science

Vol 390, Issue 6775

Scientists transplanted human cerebral organoids (“minibrains”) into rats, to better study brain disorders. The neurons grown in vivo looked more like mature human brain cells than those grown in vitro, and they made better models of Timothy syndrome. The human minibrains formed deep connections with the rat brains, received sensory information, and drove the rat’s behavior. Points of Clarification (Q&A based on common comments) Support the channel: / ihmcurious More on how minibrains are grown and used, and the issue of organoid consciousness:

• Growing “Mini-Brains” in a Lab: Human Brai… On the topic of organoid sentience and playing pong:

• Lab-Grown “Mini-Brain” Learns Pong — Is Th… Organoid transplant study: https://www.nature.com/articles/s4158… music by John Bartmann: https://johnbartmann.com