An exploration of the idea of building a Dyson Sphere or Swarm around a black hole.

My Patreon Page:

https://www.patreon.com/johnmichaelgodier.

My Event Horizon Channel:

https://www.youtube.com/eventhorizonshow.

Music:

An exploration of the idea of building a Dyson Sphere or Swarm around a black hole.

My Patreon Page:

https://www.patreon.com/johnmichaelgodier.

My Event Horizon Channel:

https://www.youtube.com/eventhorizonshow.

Music:

The FDA’s December 2025 expert panel signals a major shift in how testosterone decline, aging, and treatment access are viewed in men’s health.

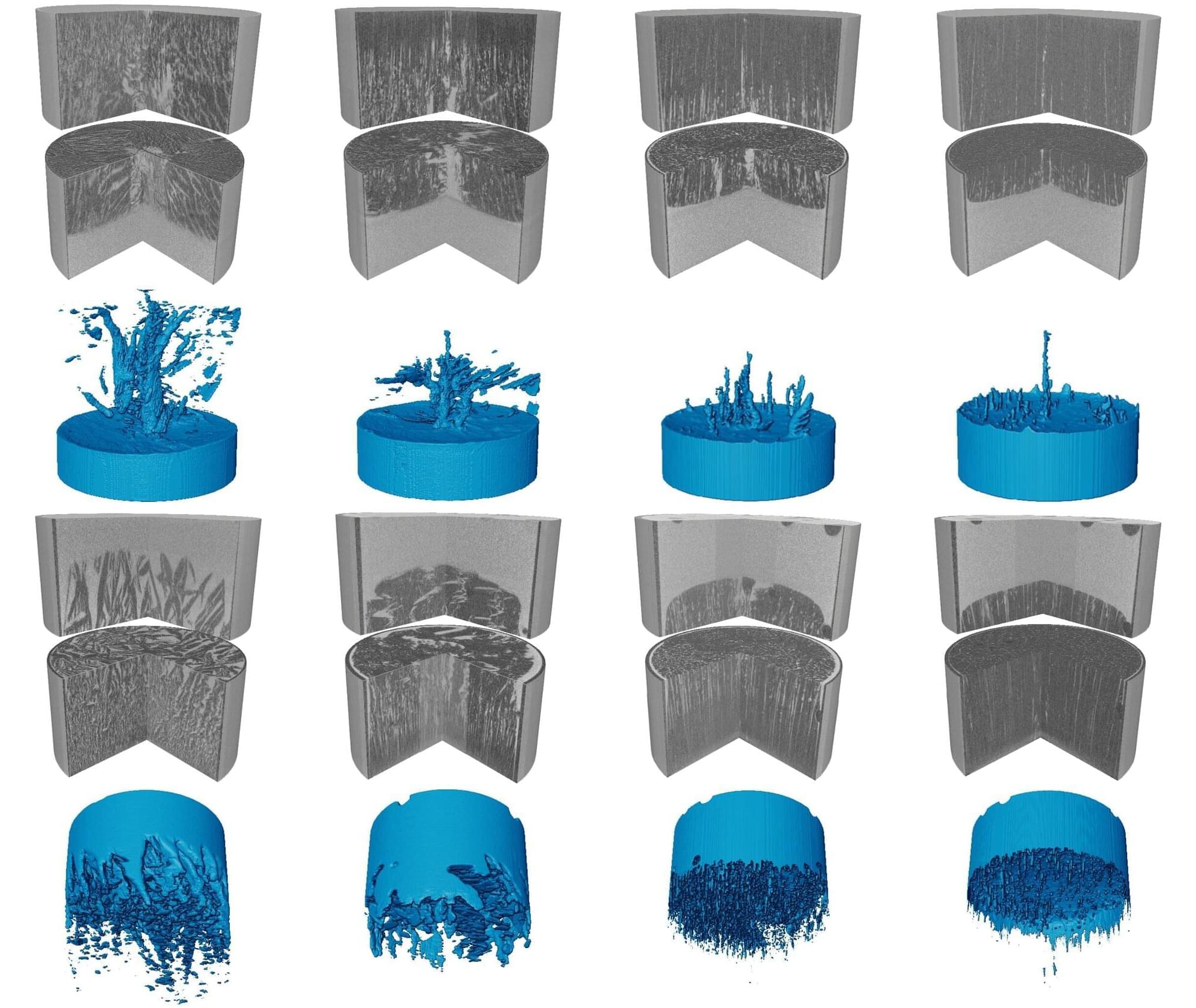

Imagine holding a narrow tube filled with salty water and watching it begin to freeze from one end. You might expect the ice to advance steadily and push the salt aside in a simple and predictable way. Yet the scene that unfolded was unexpectedly vivid.

Based on X-ray computed tomography (Micro-CT), our study, published in the Journal of Fluid Mechanics, realized the 4D (3D + time) dynamic observation and modeling of the whole process of ice crystal growth and salt exclusion.

When we monitored brine as it froze, the microstructure evolved far more dynamically than expected. Immediately after nucleation, ice crystals (dark areas) formed rapidly and trapped brine (bright areas) within a porous network. As freezing progressed, this network reorganized into striped patterns that moved either downward or upward depending on boundary conditions.

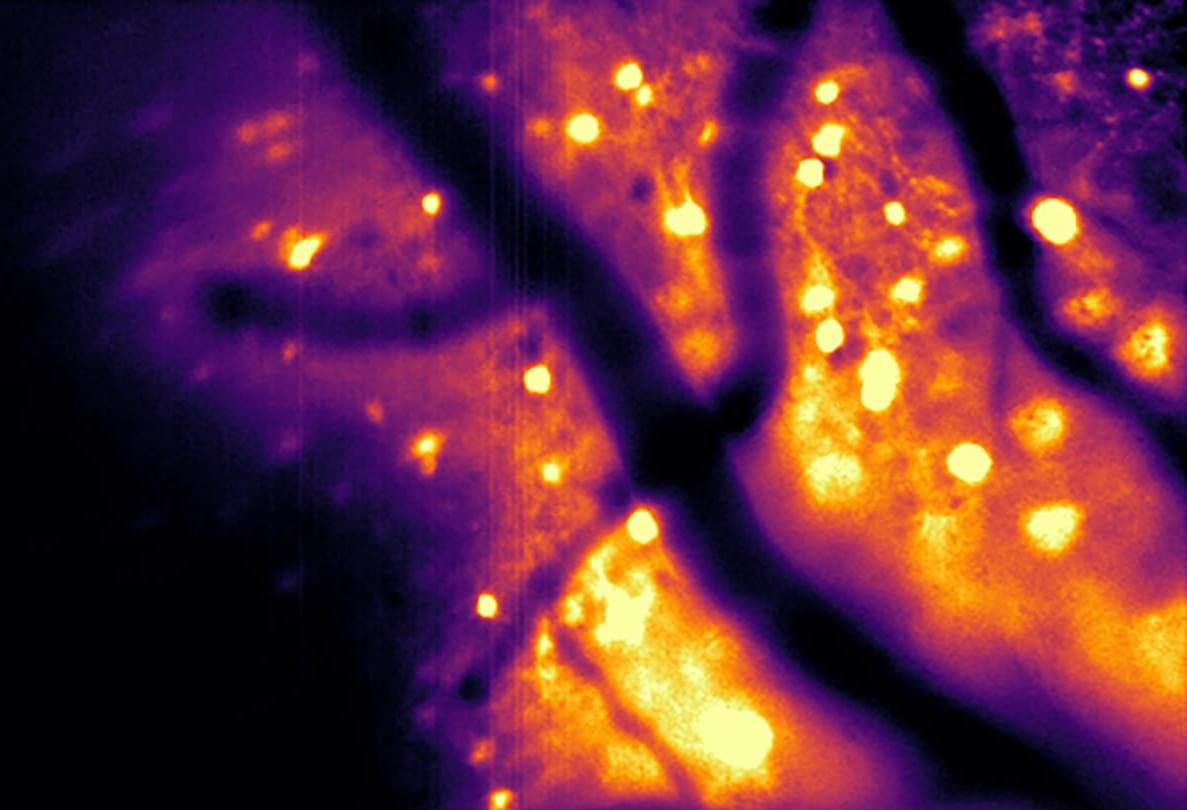

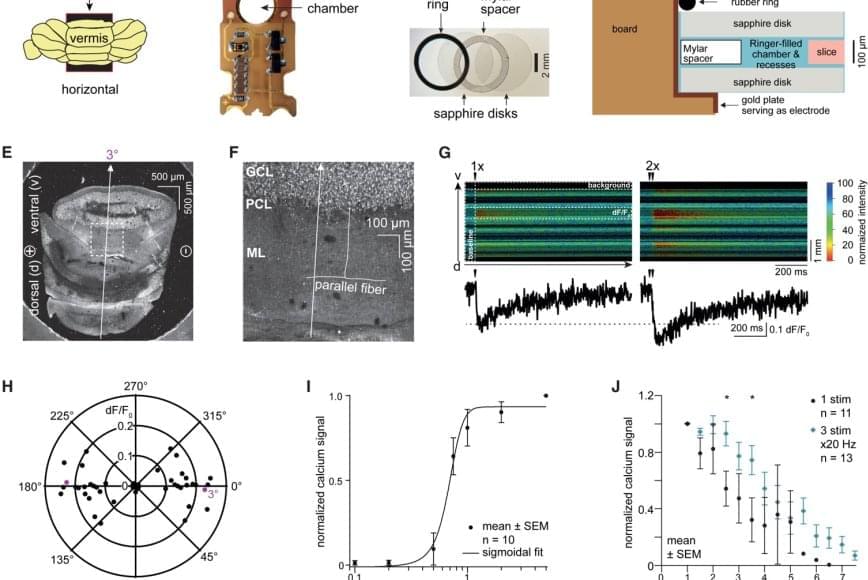

A decade ago, a group of scientists had the literally brilliant idea to use bioluminescent light to visualize brain activity.

“We started thinking: ‘What if we could light up the brain from the inside?’” said Christopher Moore, a professor of brain science at Brown University. “Shining light on the brain is used to measure activity — usually through a process called fluorescence — or to drive activity in cells to test what role they play. But shooting lasers at the brain has down sides when it comes to experiments, often requiring fancy hardware and a lower rate of success. We figured we could use bioluminescence instead.”

With a major grant from the National Science Foundation, the Bioluminescence Hub at Brown’s Carney Institute for Brain Science launched in 2017 based on collaborations between Moore (associate director of the Carney Institute), Diane Lipscombe (the institute’s director), Ute Hochgeschwender (at Central Michigan University) and Nathan Shaner (at the University of California San Diego).

The scientists’ goal was to develop and disseminate neuroscience tools based on giving nervous system cells the ability to make and respond to light.

In a study published in Nature Methods, the team described a bioluminescence tool it recently developed. Called the Ca2+ BioLuminescence Activity Monitor — or “CaBLAM,” for short — the tool captures single-cell and subcellular activity at high speeds and works well in mice and zebrafish, allowing multi-hour recordings and removing the need for external light.

More said that Shaner, an associate professor in neuroscience and in pharmacology at U.C. San Diego, led the development of the molecular device that became CaBLAM: “CaBLAM is a really amazing molecule that Nathan created,” Moore said. “It lives up to its name.”

Measuring ongoing activity of living brain cells is essential to understanding the functions of biological organisms, Moore said. The most common current approach uses imaging with fluorescence-based genetically encoded calcium-ion indicators.

As people age, these cells become defective and lose their ability to renew and repair the blood system, decreasing the body’s ability to fight infections as seen in older adults. Another example is a condition called clonal hematopoiesis; this asymptomatic condition is considered a premalignant state that increases the risk of developing blood cancers and other inflammatory disorders. Its prevalence increases significantly with age.

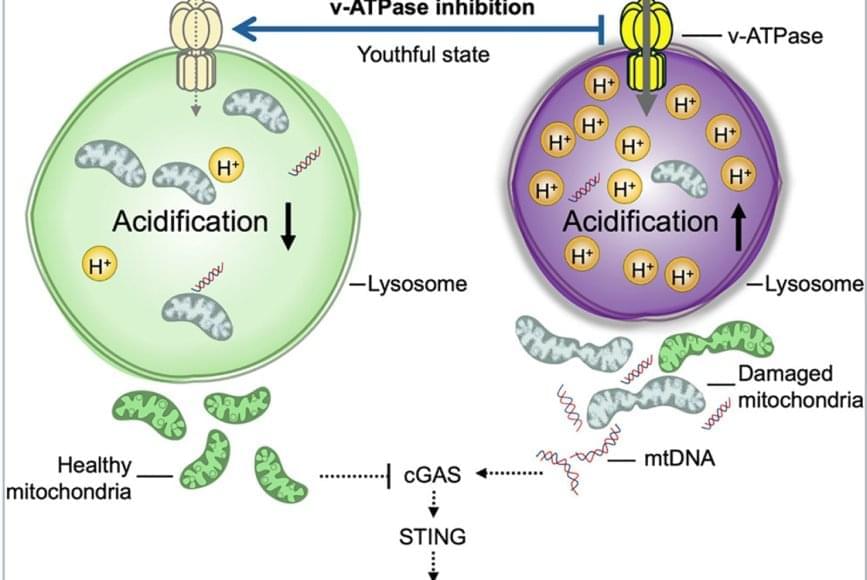

The team discovered that lysosomes in aged HSCs become hyper-acidic, depleted, damaged, and abnormally activated, disrupting the cells’ metabolic and epigenetic stability. Using single-cell transcriptomics and stringent functional assays, the researchers found that suppressing this hyperactivation with a specific vacuolar ATPase inhibitor restored lysosomal integrity and blood-forming stem cell function.

The old stem cells started acting young and healthy once more. Old stem cells regained their regenerative potential and ability to be transplanted and to produce more healthy stem cells and blood that is balanced in immune cells; they renewed their metabolism and mitochondrial function, improved their epigenome, reduced their inflammation, and stopped sending out “inflammation” signals that can cause damage in the body.

Remarkably, ex vivo treatment (when cells are removed from the body, modified in a laboratory, and returned to the body) of old stem cells with the lysosomal inhibitor boosted their in vivo blood-forming capacity more than eightfold, demonstrating that correcting lysosomal dysfunction can restore regenerative potential.

This restoration also dampened harmful inflammatory and interferon-driven pathways by improving lysosomal processing of mitochondrial DNA and reducing activation of the cGAS-STING immune signaling pathway, which they find to be a key driver of inflammation and aging of stem cells.

Researchers have discovered how to reverse aging in blood-forming stem cells in mice by correcting defects in the stem cell’s lysosomes. The breakthrough, published in Cell Stem Cell, identifies lysosomal hyperactivation and dysfunction as key drivers of stem cell aging and shows that restoring lysosomal slow degradation can revitalize aged stem cells and enhance their regenerative capacity.

For the new study, the researchers used samples from the brains of normal mice as well as living cortical brain tissue sampled with permission from six individuals undergoing surgical treatment for epilepsy. The surgical procedures were medically necessary to remove lesions from the brain’s hippocampus.

The researchers first validated the zap-and-freeze approach by observing calcium signaling, a process that triggers neurons to release neurotransmitters in living mouse brain tissues.

Next, the scientists stimulated neurons in mouse brain tissue with the zap-and-freeze approach and observed where synaptic vesicles fuse with brain cell membranes and then release chemicals called neurotransmitters that reach other brain cells. The scientists then observed how mouse brain cells recycle synaptic vesicles after they are used for neuronal communication, a process known as endocytosis that allows material to be taken up by neurons.

The researchers then applied the zap-and-freeze technique to brain tissue samples from people with epilepsy, and observed the same synaptic vesicle recycling pathway operating in human neurons.

In both mouse and human brain samples, the protein Dynamin1xA, which is essential for ultrafast synaptic membrane recycling, was present where endocytosis is thought to occur on the membrane of the synapse.

“Our findings indicate that the molecular mechanism of ultrafast endocytosis is conserved between mice and human brain tissues,” the author says, suggesting that the investigations in these models are valuable for understanding human biology.