Innovative techniques being developed to detect gravitational waves beyond the current capabilities of laser interferometers like LIGO and Virgo.

That rare bright spot looks set to become brighter.

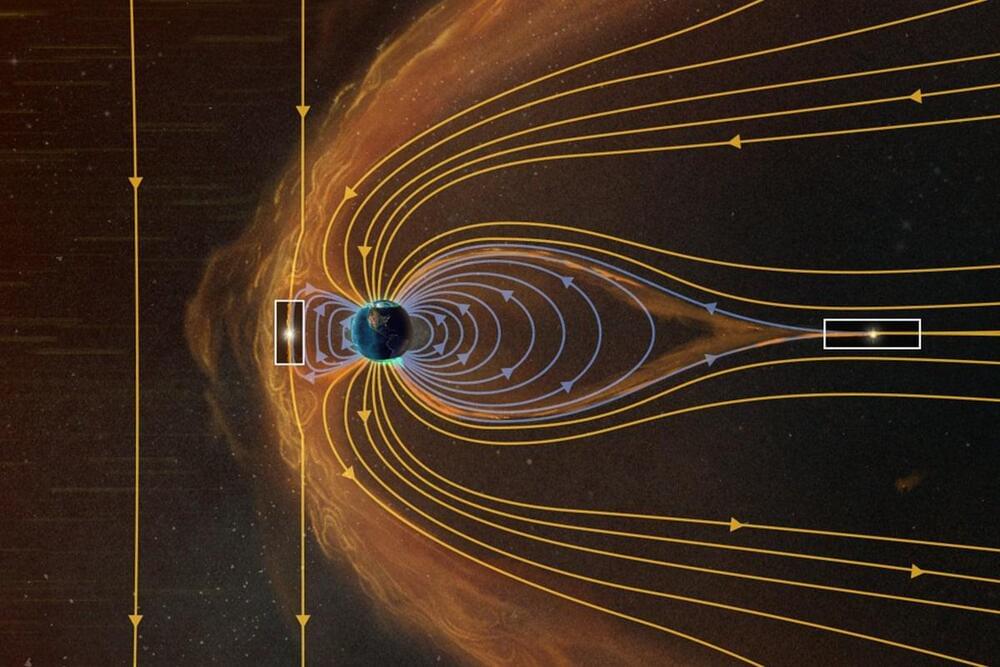

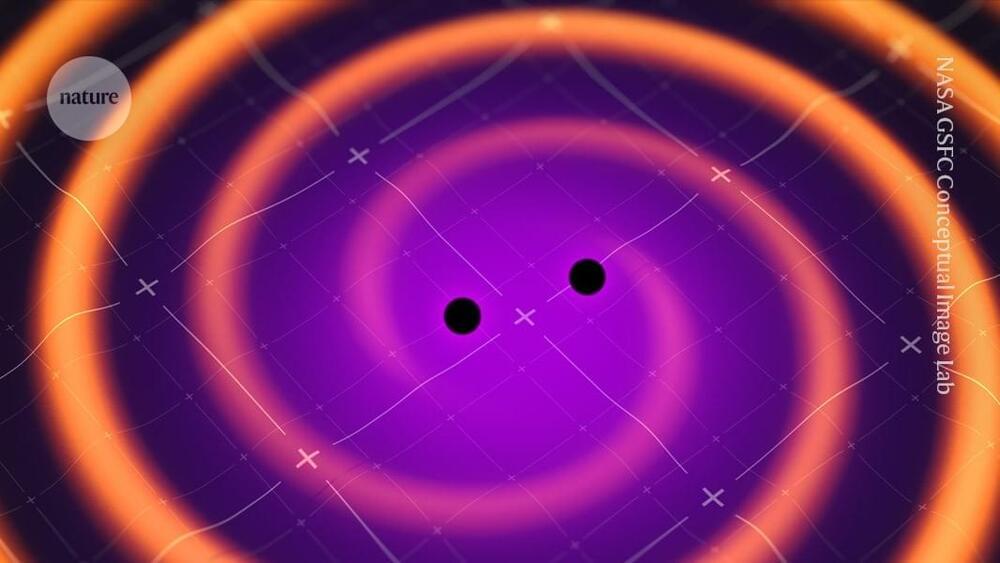

All of the more than 100 gravitational-wave events spotted so far have been just a tiny sample of what physicists think is out there. The window opened by LIGO and Virgo was rather narrow, limited mostly to frequencies in the range 100–1,000 hertz. As pairs of heavy stars or black holes slowly spiral towards each other, over millions of years, they produce gravitational waves of slowly increasing frequency, until, in the final moments before the objects collide, the waves ripple into this detectable range. But this is only one of many kinds of phenomenon that are expected to produce gravitational waves.

LIGO and Virgo are laser interferometers: they work by detecting small differences in travel time for lasers fired along perpendicular arms, each a few kilometres long. The arms expand and contract by minuscule amounts as gravitational waves wash over them. Researchers are now working on several next-generation LIGO-type observatories, both on Earth and, in space, the Laser Interferometer Space Antenna; some have even proposed building one on the Moon1. Some of these could be sensitive to gravitational waves at frequencies as low as 1 Hz.