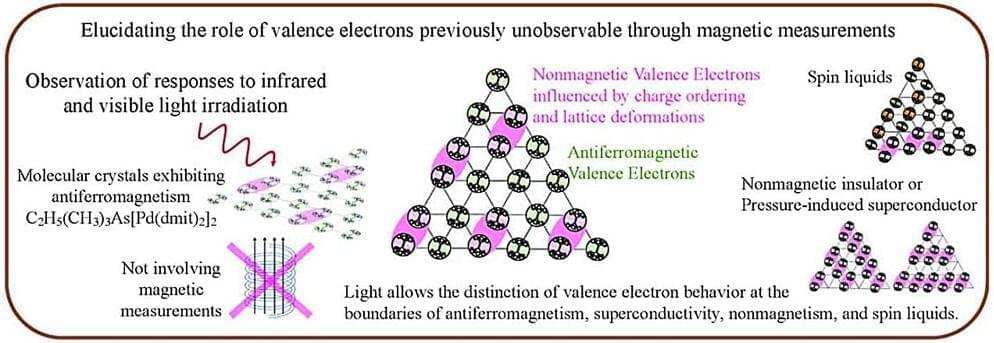

Molecular crystals with conductivity and magnetism, due to their low impurity concentrations, provide valuable insights into valence electrons. They have helped link charge ordering to superconductivity and to explore quantum spin liquids, where electron spins remain disordered even at extremely low temperatures.

Valence electrons with quantum properties are also expected to exhibit emergent phenomena, making these crystals essential for studying novel material functionalities.

However, the extent to which valence electrons in molecular crystals contribute to magnetism remains unclear, leaving their quantum properties insufficiently explored. To address this, a research team used light to analyze valence electron arrangements, building on studies of superconductors and quantum spin liquids. The findings are published in Physical Review B.