Longevity don’t lead to demographic crisis.

Explains why the improvement of health is not a danger.

As counterintuitive as it may seem, population sizes don’t go up as the world gets healthier. They go down. Here’s why.

Longevity don’t lead to demographic crisis.

Explains why the improvement of health is not a danger.

As counterintuitive as it may seem, population sizes don’t go up as the world gets healthier. They go down. Here’s why.

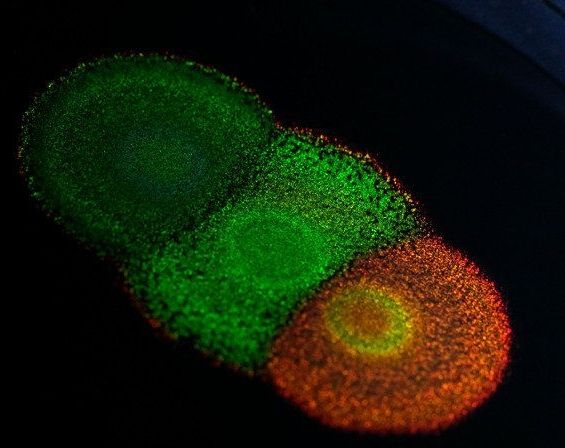

Researchers have unlocked the genetic code behind some of the brightest and most vibrant colours in nature. The paper, published in the journal PNAS, is the first study of the genetics of structural colour — as seen in butterfly wings and peacock feathers — and paves the way for genetic research in a variety of structurally coloured organisms.

The study is a collaboration between the University of Cambridge and Dutch company Hoekmine BV and shows how genetics can change the colour, and appearance, of certain types of brightly-coloured bacteria. The results open up the possibility of harvesting these bacteria for the large-scale manufacturing of nanostructured materials: biodegradable, non-toxic paints could be ‘grown’ and not made, for example.

Flavobacterium is a type of bacteria that packs together in colonies that produce striking metallic colours, which come not from pigments, but from their internal structure, which reflects light at certain wavelengths. Scientists are still puzzled as to how these intricate structures are genetically engineered by nature, however.

The experiment was held near the isolated Israeli township of Mitzpe Ramon, whose surroundings resemble the Martian environment in its geology, aridity, appearance and desolation, the ministry said.

The participants were investigating various fields relevant to a future Mars mission, including satellite communications, the psychological affects of isolation, radiation measurements and search ing for life signs in soil.

Participant Guy Ron, a nuclear physics professor from the Hebrew University in Jerusalem, said the project was not only intended to look for new approaches in designing a future mission to the Red Planet, but to increase public interest.

Ninety-five new exoplanets — planets that orbit around stars other than our sun — can now be added to the long list of planets that have been discovered since the 1990s.

The discovery was made by a Danish Ph.D. student with the help of the once damaged Kepler telescope, reports ScienceNordic.

Andrew Mayo from the Technical University of Denmark (DTU Space) is behind the discovery, which is described in a new study.

Intel and Researchers from Heidelberg and Dresden present three new neuromorphic chips.

Researchers from Heidelberg University and TU Dresden, together with Intel Corporation, will reveal three new neuromorphic chips during the NICE Workshop 2018 in the USA. These chips have an extraordinary ability: They are able to mimic important aspects of biological brains by being energy efficient, resilient and able to learn. These chips promise to have a major impact on the future of artificial intelligence. Computers are many times faster than humans in solving arithmetical problems, yet they have thus far been no match when it comes to the analytic ability of the brain. Up until now, computers have not been able to continually learn and can therefore not improve themselves. The two European chips were developed in close collaboration with neuroscientists as part of the Human Brain Project of the European Union. NICE 2018 will be held from 27 February until 1 March on the Intel Campus in Hillsboro/Oregon.

Dr Johannes Schlemmel from the Kirchhoff Institute for Physics at Heidelberg University will present prototypes of the new BrainScaleS chip. BrainScaleS has a mixed analogue and digital design and works 1,000 to 10,000 times faster than real time. The second generation neuromorphic BrainScaleS chip has freely programmable on-chip learning functions as well as an analogue hardware model of complex neurons with active dendritic trees, which – based on nerve cells – are especially valuable for reproducing the continual process of learning.

Dr Ian Pearson, a leading futurologist from Ipswich, claims that if people can survive until 2050 they could live forever thanks to advances in AI, android bodies and genetic engineering.

AUSTIN, Texas — Mining asteroids for water and other resources could someday become a trillion-dollar business, but not without astronomers to point the way.

At least that’s the view of Martin Elvis, a researcher at the Harvard-Smithsonian Center for Astrophysics, who’s been taking a close look at the science behind asteroid mining.

If the industry ever takes off the way ventures such as Redmond, Wash.-based Planetary Resources and California-based Deep Space Industries hope, “that opens up new employment opportunities for astronomers,” Elvis said today in Austin at the annual meeting of the American Association for the Advancement of Science.