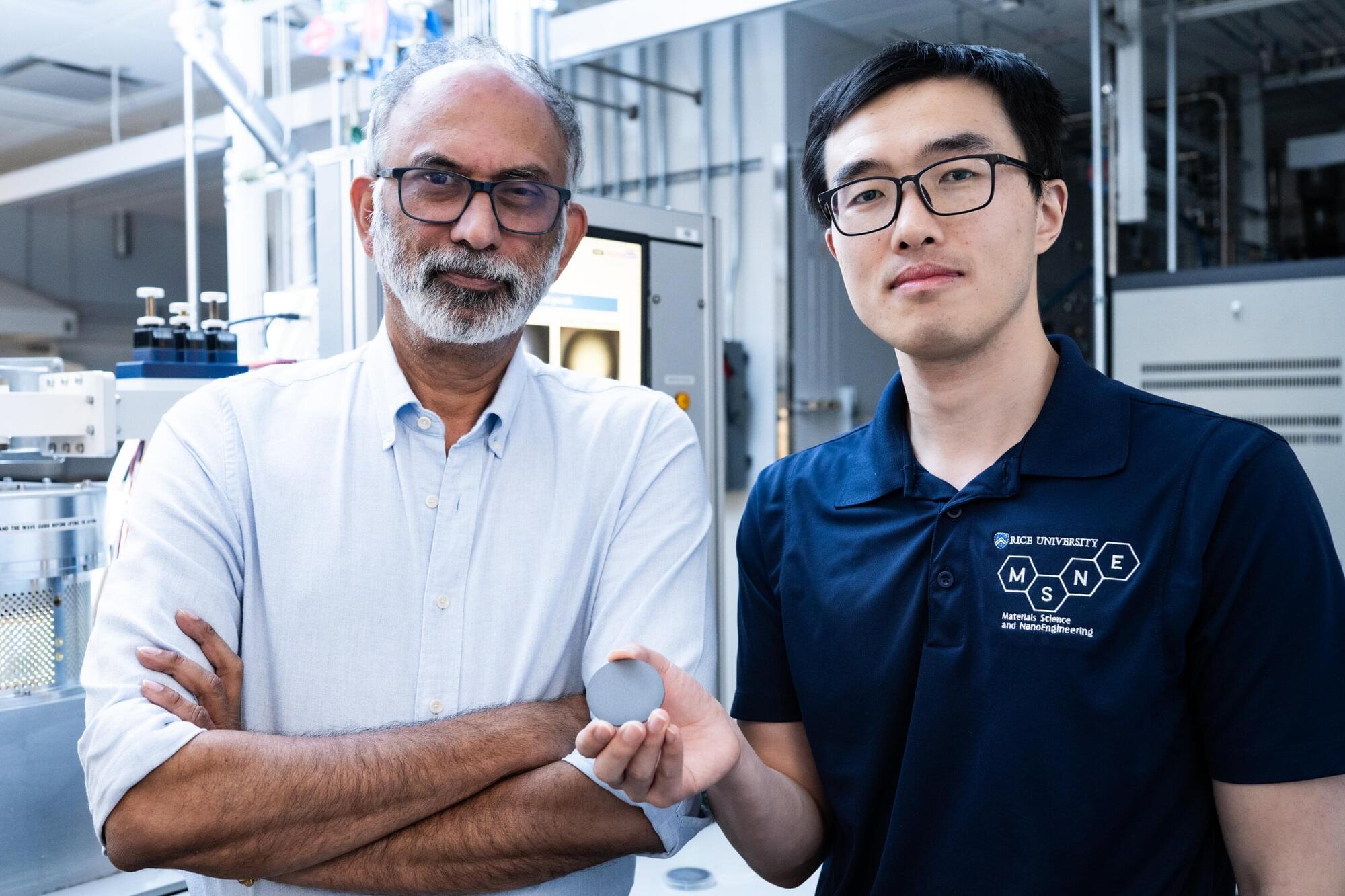

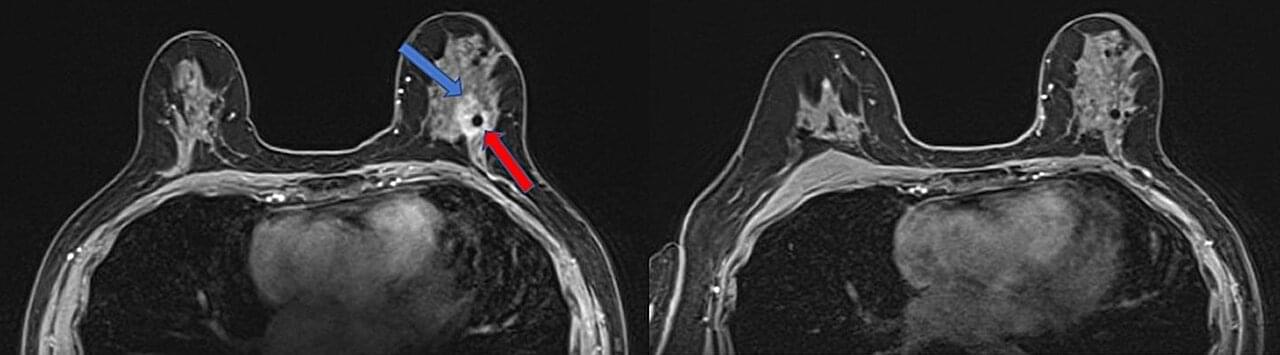

A single, targeted high dose of radiation delivered before other treatments could completely eradicate tumors in most women with early-stage, operable hormone-positive breast cancer, according to a study led by UT Southwestern Medical Center researchers. The findings, published in JAMA Network Open, could shift the paradigm for patients with the most common form of breast cancer, who typically undergo surgery before a regimen of radiation therapy.

“This is a major advance in the field,” said study leader Asal Rahimi, M.D., Professor of Radiation Oncology, Associate Vice Chair for Program Development, and Medical Director of the Clinical Research Office at the Harold C. Simmons Comprehensive Cancer Center. “This treatment protocol provides patients a significant time savings, spares a lot of their tissue from irradiation, and allows them to still undergo any type of oncoplastic surgery they may choose, all while very effectively treating their disease.”