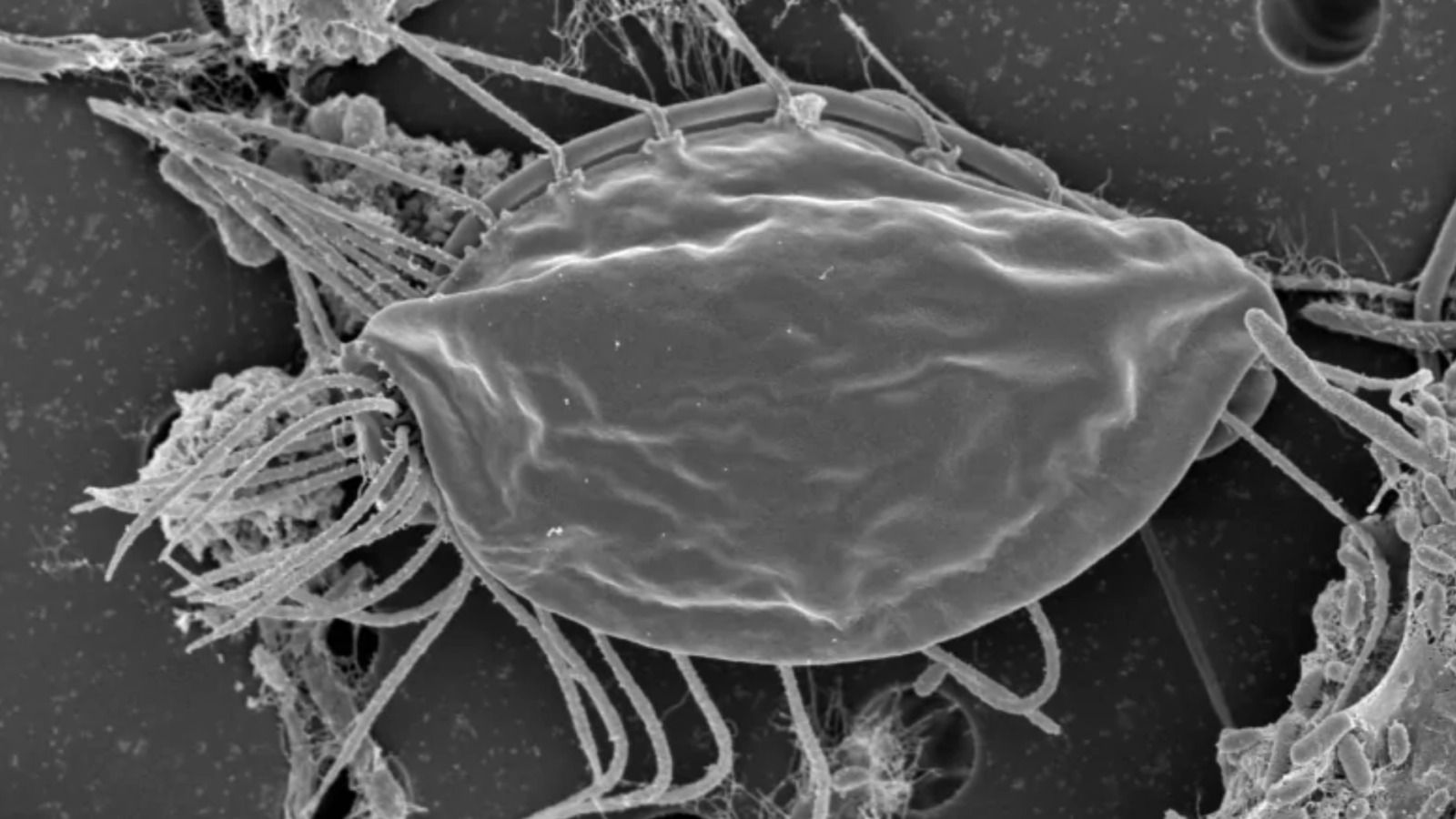

A tiny transparent worm could be the key to finding out how to stop the frailty and ill health which often comes with old age.

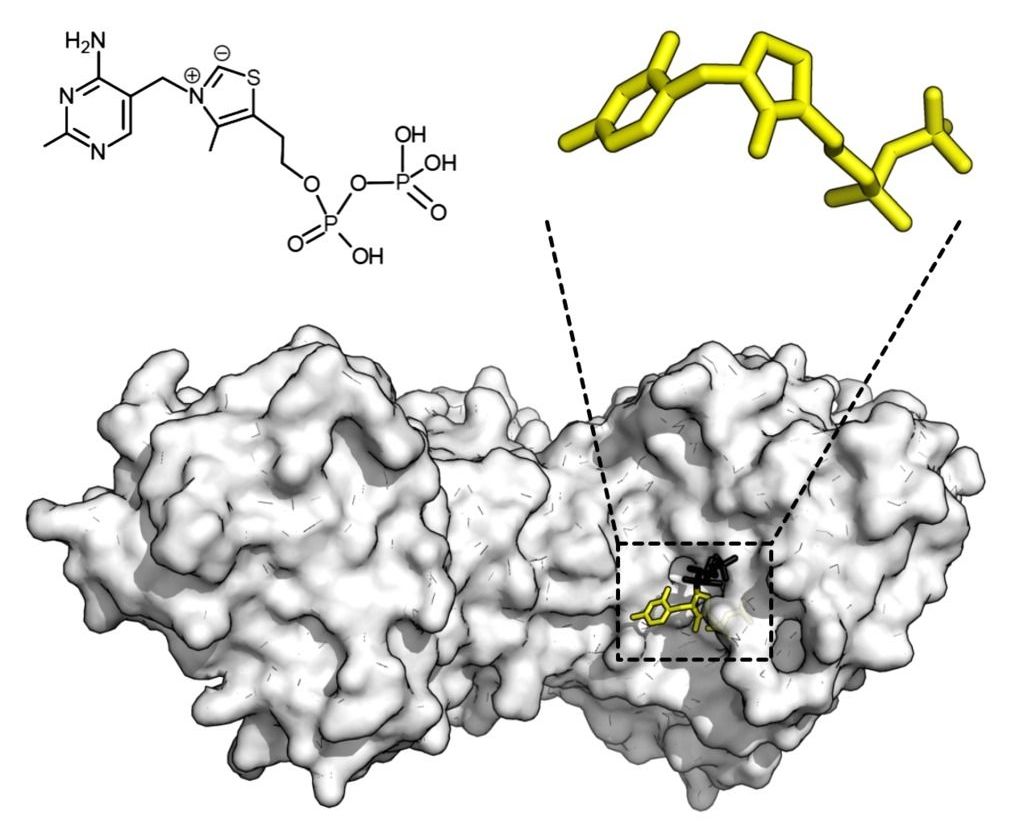

British scientists are sending tens of thousands of worms into space in a government backed project to see if two drugs can prevent or slow down muscle wasting brought on by microgravity.

In space, the 1mm long c-elegans worms have nothing to push against to maintain their muscle mass and so quickly start losing strength, mirroring the effect experienced by elderly people back on Earth or those with conditions like muscular dystrophy.