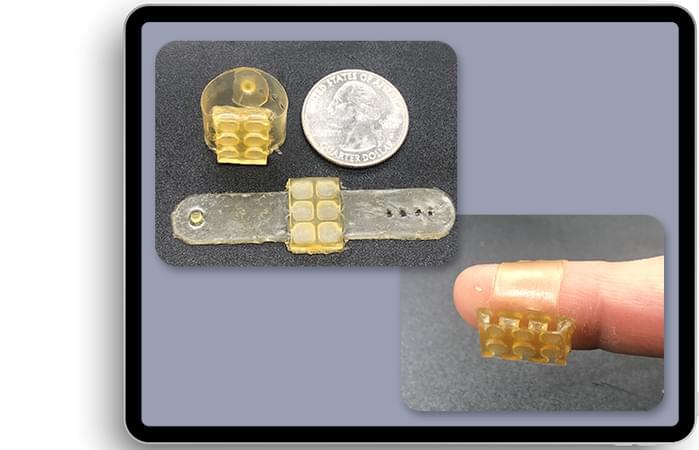

Aside from faster results, edge computing has the added benefit of increased privacy: If your health information never leaves your wearable, you don’t have to worry about someone else intercepting it — or interfering with it — en route.

So why do we run these apps in the cloud, instead of locally? The problem is that wireless devices have limited processing power and battery — to run a more advanced and energy-intensive AI program, you may have to turn to huge servers in the cloud.

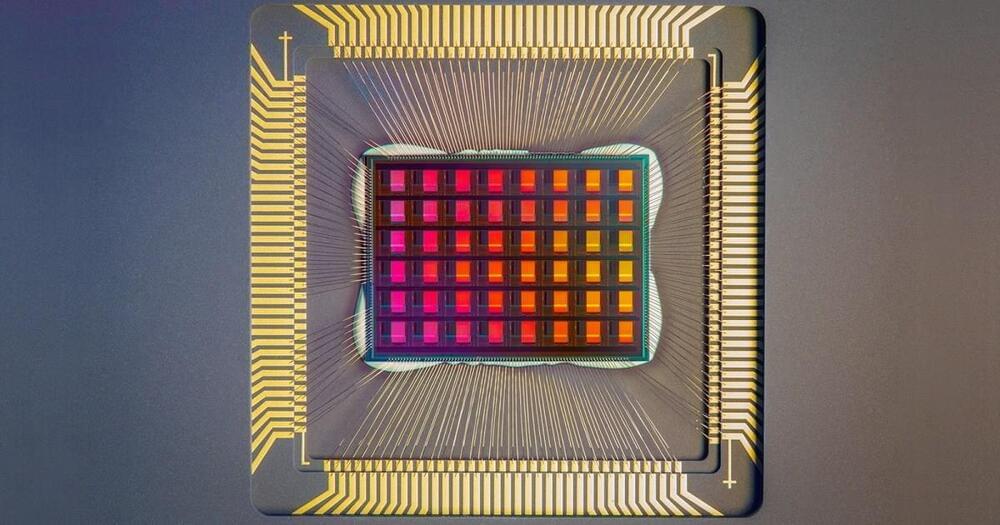

A Stanford-led team has now unveiled NeuRRAM, a new microchip that could let us run advanced AI programs directly on our devices.