The new Solos AirGo3 Smartglasses look like regular frames, but feature ChatGPT, making them more than another pair of audio smartglasess, and they’re priced at an accessible $199.99.

Smartglasses just got a lot smarter.

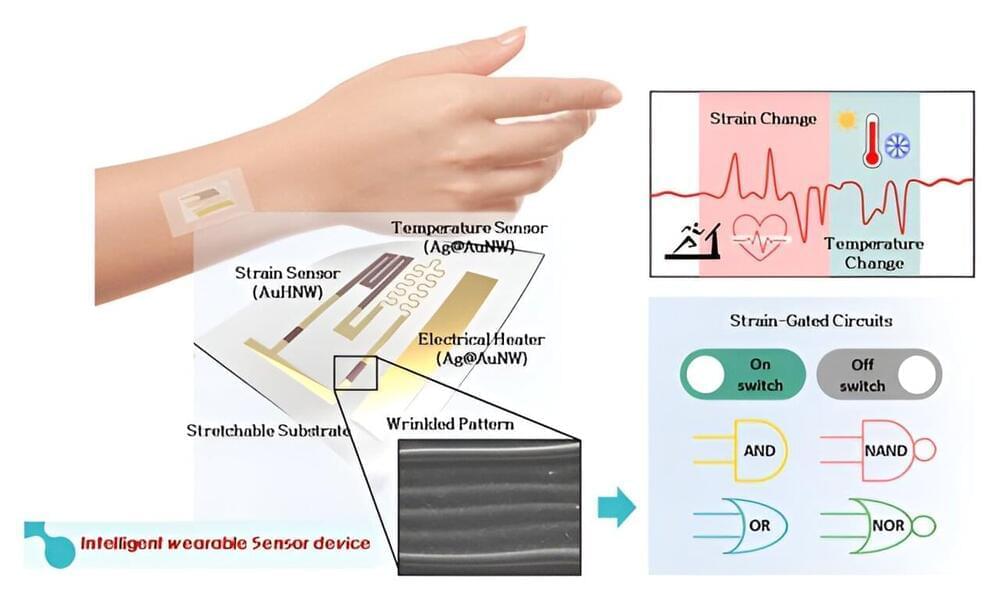

A research team led by Professor Sei Kwang Hahn and Dr. Tae Yeon Kim from the Department of Materials Science and Engineering at Pohang University of Science and Technology (POSTECH) used gold nanowires to develop an integrated wearable sensor device that effectively measures and processes two bio-signals simultaneously. Their research findings were featured in Advanced Materials.

Wearable devices, available in various forms like attachments and patches, play a pivotal role in detecting physical, chemical, and electrophysiological signals for disease diagnosis and management. Recent strides in research focus on devising wearables capable of measuring multiple bio-signals concurrently.

However, a major challenge has been the disparate materials needed for each signal measurement, leading to interface damage, complex fabrication, and reduced device stability. Additionally, these varied signal analyses require further signal processing systems and algorithms.

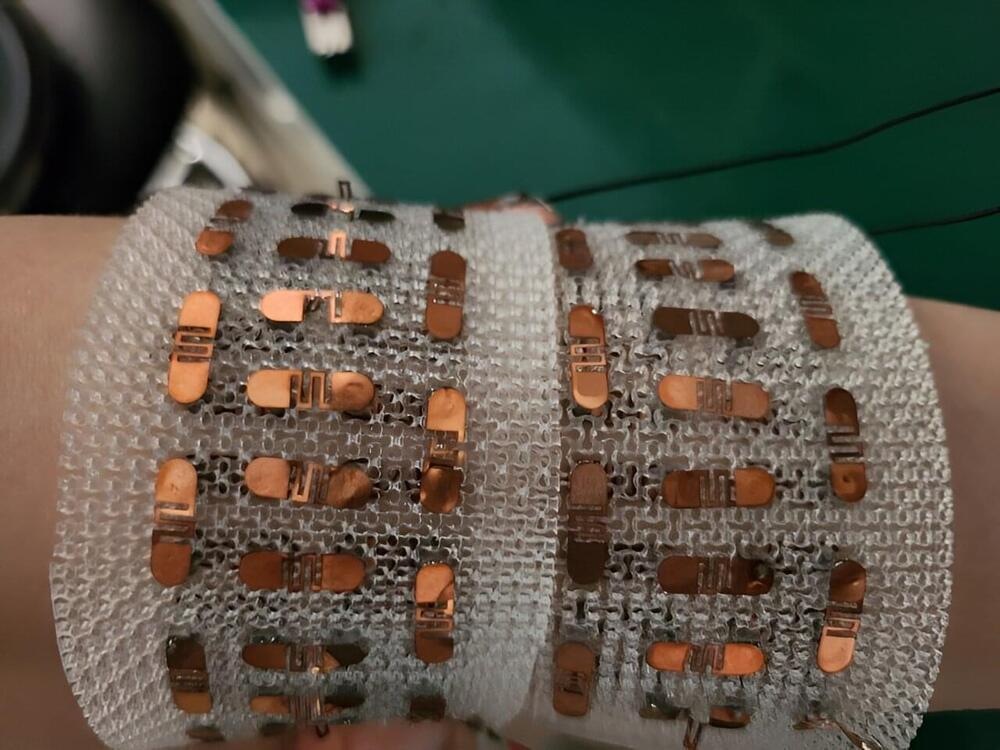

Dr. Hyekyoung Choi and Min Ju Yun’s research team from the Energy Conversion Materials Research Center, Korea Electrotechnology Research Institute (KERI), has developed a technology that can increase the flexibility and efficiency of a thermoelectric generator to the world’s highest level by using “mechanical metamaterials” that do not exist in nature. The research results were published in Advanced Energy Materials.

In general, a material shrinks in the vertical direction when it is stretched in the horizontal direction. It is like when you press a rubber ball, it flattens out sideways, and when you pull a rubber band, it stretches tightly.

The amount of transversal elongation divided by the amount of axial compression is Poisson’s ratio. Conversely, mechanical metamaterials, unlike materials in nature, are artificially designed to expand in both the horizontal and vertical directions when it is stretched in the horizontal direction. Metamaterials have a negative Poisson’s ratio.

The devices demonstrated clinical-grade accuracy and introduced novel functionalities not seen in prior research or clinical care.

Northwestern University.

Furthering the scope of such examinations, a team of researchers at Northwestern University (NU) is now presenting novel wearable technology much more advanced than the intermittent measures made during periodic medical examinations.

Throughout history, sonar’s distinctive “ping” has been used to map oceans, spot enemy submarines and find sunken ships. Today, a variation of that technology – in miniature form, developed by Cornell researchers – is proving a game-changer in wearable body-sensing technology.

PoseSonic is the latest sonar-equipped wearable from Cornell’s Smart Computer Interfaces for Future Interactions (SciFi) lab. It consists of off-the-shelf eyeglasses outfitted with micro sonar that can track the wearer’s upper body movements in 3D through a combination of inaudible soundwaves and artificial intelligence (AI).

With further development, PoseSonic could enhance augmented reality and virtual reality, and track detailed physical and behavioral data for personal health, the researchers said.

Published 6 seconds ago.

We’re getting one step closer to wearable Star Trek technology in the form of a new device called the “Ai Pin.” (via Humane). The AI Pin was created by a startup company called Humane, which is primarily led by ex-Apple employees who want to transform how we interact with our devices.

A first-of-its-kind flexible sensor turns a pair of earbuds into a device capable of recording brain activity and analyzing sweat, making them useful for diagnosing diseases and health monitoring.

The background: Health monitoring wearables can measure our blood pressure, track our heart rates, and even detect infections before we start to feel sick, helping us take better care of ourselves and potentially even giving us a way to prevent the spread of diseases.

The devices are useless if no one wants to wear them, though, so finding designs that are comfortable and easy to integrate into daily life is key. Because earbuds are already popular, researchers have used them as the basis for health monitoring devices that record brain activity to predict strokes, epileptic seizures, or Parkinson’s disease.

The future of smart glasses is about to change drastically with the upcoming release of DigiLens ARGO range next year. These innovative smart glasses will be powered by Phantom Technology’s cutting-edge spatial AI assistant, CASSI. This partnership between DigiLens, based in Silicon Valley, and Phantom Technology, located at St John’s Innovation Centre, brings together the expertise of both companies to create a game-changing wearable device.

Phantom Technology, an AI start-up founded by a group of brilliant minds, has been working diligently over the years to develop advanced human interface technologies for AI wearables. Their breakthrough 3D imaging technology allows users to identify objects in their environment, enhancing their overall experience. With DigiLens incorporating Phantom’s patented optical platform into their consumer product, customers can expect a new era of smart glasses with unparalleled features.

CASSI, the novel spatial AI assistant designed by Phantom Technology, aims to boost productivity and awareness in enterprise settings. This innovative assistant combines computer vision algorithms with a large language model, enabling users to receive step-by-step instructions and assistance for various tasks. Imagine effortlessly locating any physical object or destination in the real world with 3D precision, using your voice to generate instructions, and seamlessly managing tasks using augmented reality.

They’re called vibrotactors and they vibrate to provide orientation cues.

A number of factors, such as the lack of gravity, changed sensory inputs, and the unique conditions of space travel, can cause disorientation in astronauts. This phenomenon is so severe that it can even be deadly to the space dwellers.

A new path for safer space travel

Usually, astronauts must undergo extensive training to guard against it. However, researchers have now released a new study that shows that wearable gadgets called vibrotactors that vibrate to provide orientation cues may greatly increase the effectiveness of this training providing a new path to making space travel safer and more comfortable for astronauts.

“Long duration spaceflight will cause many physiological and psychological stressors which will make astronauts very susceptible to spatial disorientation,” said Dr Vivekanand P. Vimal of Brandeis University in the United States, lead author of the research. “When disoriented, an astronaut will no longer be able to rely on their own internal sensors which they have depended on for their whole lives.”

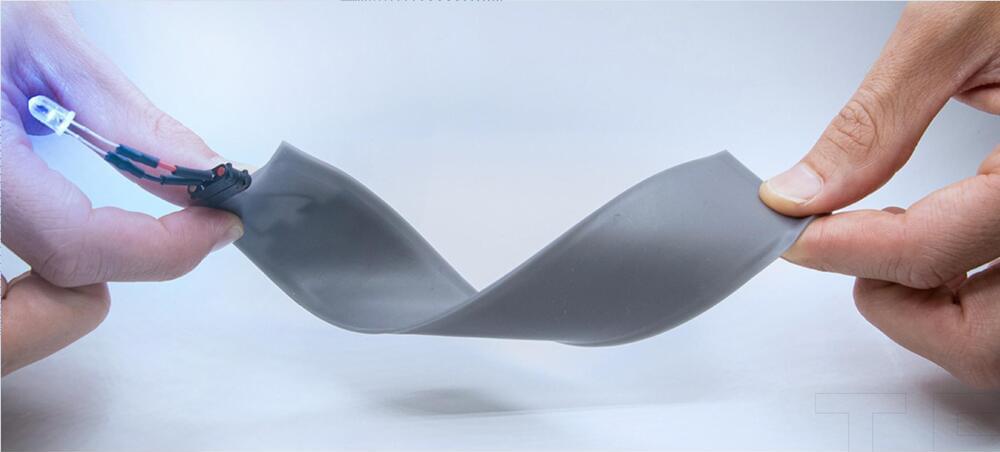

Batteries are regarded as crucial technologies in the battle against climate change, particularly for electric vehicles and storing energy from renewable sources. Anthro Energy’s novel flexible batteries are presently available to wearable manufacturers and could be employed in a variety of areas, including electric cars and laptops.

The innovative batteries score well in fire safety, thanks to new materials and design features that eliminate internal and external mechanical safety risks like explosions. Many of today’s batteries, such as lithium-ion batteries, contain a flammable liquid as an electrolyte.

Anthro Energy’s David Mackaniac and his team have created a flexible polymer electrolyte that is malleable like rubber. The new technology provides increased design flexibility for use across a range of devices, with adaptable shapes and sizes to suit specific applications.