Offutt will receive three refurbished tankers-turned-nuclear reconnaissance planes in the next year.

GM unveiled Monday evening the Chevrolet Blazer EV, an all-electric SUV with up to 320 miles of range and a starting price of $48,000 that CEO and Chairman Mary Barra hopes will supercharge her bid to surpass Tesla in U.S. EV sales by 2025.

The Chevrolet Blazer EV, which will go on sale in 2023 as a 2024 model year, isn’t the only impending GM electric vehicle. A slew of Cadillac and Chevy EVs are also making their way to market. But the Blazer, at its more affordable price point and in the lucrative SUV segment, could kick-start GM’s sales goals.

Internally, the confidence is high. Blazer is going be a massive statement and illustrate how GM can hit big volume segments, according to Scott Bell, Global VP of Chevrolet.

Passengers travelling on a Spanish train were alarmed as their train momentarily stopped and wildfires could be seen on both sides of the track.

The footage was captured in the Spanish province of Zamora.

A spokesperson from rail operator Adif told the Associated Press that the passengers were never in danger.

We live in an increasingly connected world, a fact underscored by the swift spread of the coronavirus around the globe. Underlying this connectivity are complex networks—global air transportation, the internet, power grids, financial systems and ecological networks, to name just a few. The need to ensure the proper functioning of these systems also is increasing, but control is difficult.

Now a Northwestern University research team has discovered a ubiquitous property of a complex network and developed a novel computational method that is the first to systematically exploit that property to control the whole network using only local information. The method considers the computational time and information communication costs to produce the optimal choice.

The same connections that provide functionality in networks also can serve as conduits for the propagation of failures and instabilities. In such dynamic networks, gathering and processing all the information necessary to make a better decision can take too much time. The goal is to diagnose a problem and take action before it leads to a system-wide issue. This may mean having less information but being timely.

The 6 million-square-foot Samsung plant will be located south of Highway 79 and southwest of Downtown Taylor, near Taylor High School. It is expected to bring 1,800 jobs to Williamson County.

The plant is expected to start operations in 2024. The City of Taylor, Williamson County and Taylor ISD all already have economic agreements in place related to Samsung’s development.

To learn more, read Community Impact’s full report.

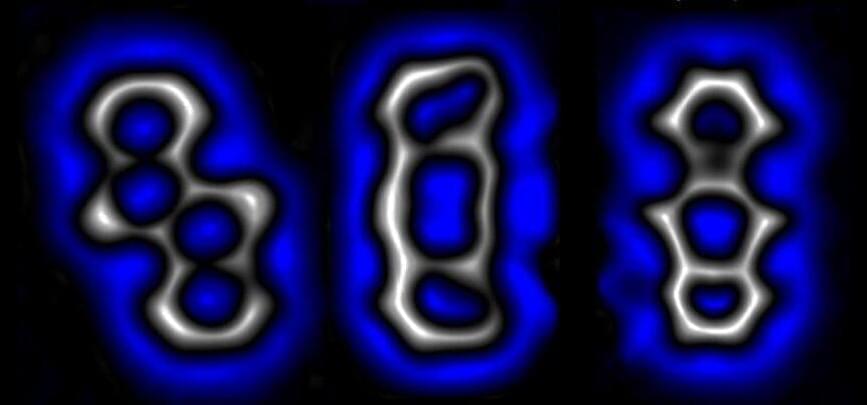

So precise.

If chemists built cars, they’d fill a factory with car parts, set it on fire, and sift from the ashes pieces that now looked vaguely car-like.

When you’re dealing with car-parts the size of atoms, this is a perfectly reasonable process. Yet chemists yearn for ways to reduce the waste and make reactions far more precise.

Chemical engineering has taken a step forward, with researchers from the University of Santiago de Compostela in Spain, the University of Regensburg in Germany, and IBM Research Europe forcing a single molecule to undergo a series of transformations with a tiny nudge of voltage.